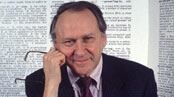

Like most Americans, I knew William Safire through his public biography: the “kitchen debate,” the “nattering nabobs,” the political commentary, the columns on language. But since coming to the National Endowment for the Arts, I have discovered a different aspect of Mr.