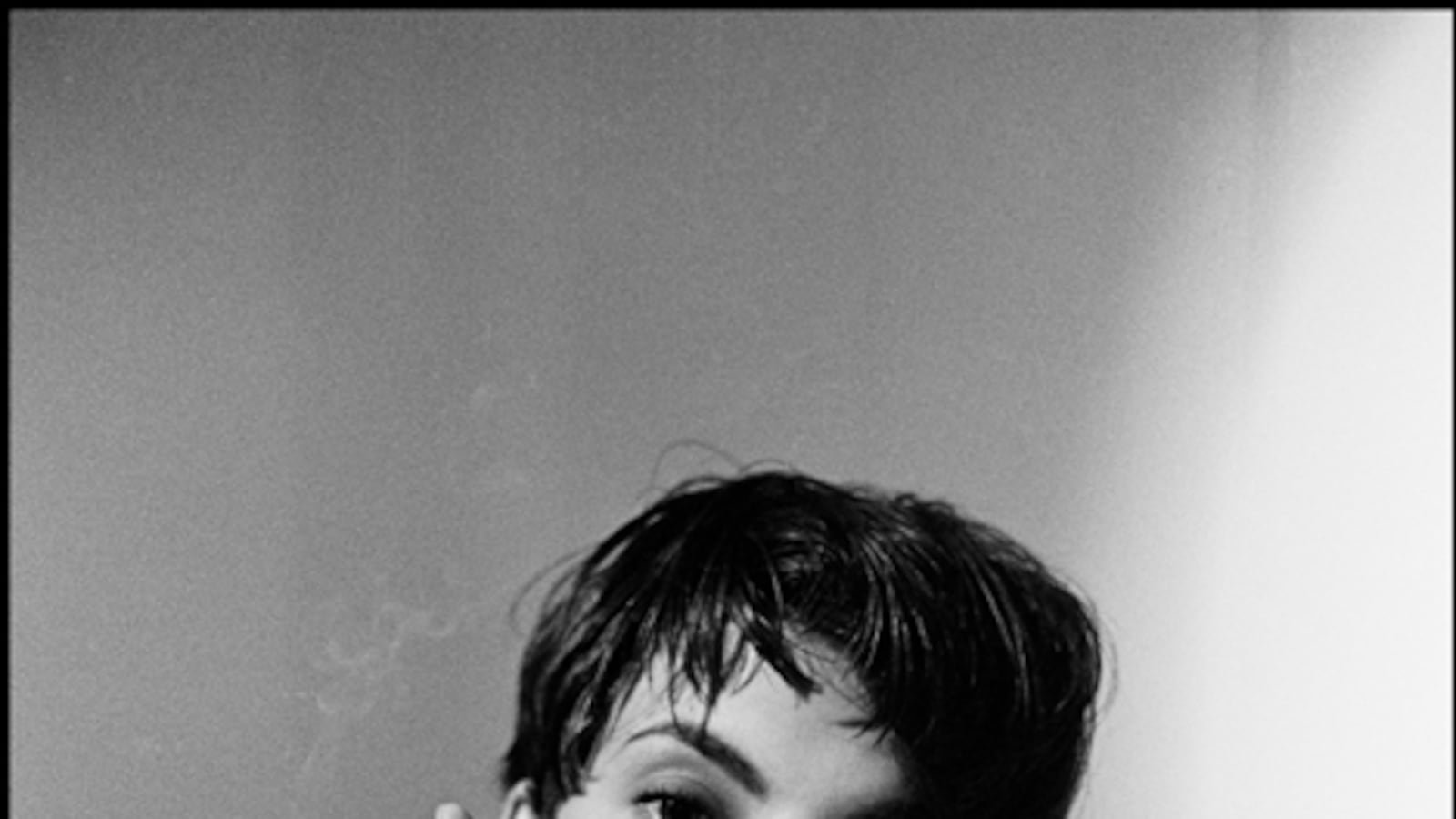

The photographer Arthur Elgort changed the way the common man relates to fashion. Instead of depicting models as perfect swans with their heads tilted just so, or as haughty mannequins both inaccessible and unbelievable, he turned a journalistic eye on them and their impractical clothes. He caught them in mid-stride, engaged in gossip or head tossed back in raucous laughter. For other photographers, models arched their backs and posed. For Elgort, they twirled and leapt. Their haphazard, sometimes awkward, energy made them seem imperfect and alive. Endearing and captivating. His work is often like a glorious collection of snapshots, able to convince viewers that some dazzling gazelle dripping in Chanel just might come bounding through their neighborhood.

Elgort, 70, will be honored June 6 in New York City by the Council of Fashion Designers of America. But he isn't receiving kudos merely for fashion photography—he'll be honored with a Board of Directors Award, a sort of high-falutin' thank-you for changing an entire industry for the better.

Though not a journalist by training—he grew up in New York City and studied painting at Hunter College—Elgort travels light, always has a camera in hand, and has a newsman's eye for catching an unexpected moment. He is driven by a love for dance and jazz, and in his photography those twin enthusiasms emerge as a passion for expansive movement and improvisation.

"In the '70s, I didn't use a flash, and I would go outside and look for instances where I could capture that naturalness," he explains in an email; he's recovering from a recent stroke, and his speech doesn't come as easily as before. Still, he continues to work behind the camera. "I was used to movement because I started as a dance photographer," he writes. "You have to be a little faster, and you have to know some tricks" like moving with the model. "I like movement in photography very much, but I wasn't trying to change fashion photography, he adds. "I was just thinking about getting a job and doing it well and taking a good picture."

On shoots, Elgort will watch, chat—and, most important, wait. On a Vogue magazine shoot back in 1995, an entire afternoon's worth of photographs led to a spectacular splash when model Stella Tennant, hot and tired from working in winter tweeds under the summer sun—which is so often the case in an industry that gallops along six months ahead of the rest of us—took a leap into a pool of water, still dressed in her designer duds. Now that was the picture Elgort had been waiting for!

"He just sort of keeps talking and shooting, and eventually the models' defenses break down and they're just quite happy to leap over a wall," says his longtime friend and collaborator, Grace Coddington, the flame-haired Vogue editor made famous in the 2009 documentary The September Issue.

Elgort's patience also pays off in small, sweet ways. There was nothing more charming than his recent photograph, again for Vogue, of model Liya Kebede alongside her husband and two children. Elgort stole a precious moment when Kebede's little daughter peered curiously under the hem of her mother's long dress.

"He just sort of keeps talking and shooting, and eventually the models' defenses break down and they're just quite happy to leap over a wall."

"He brought joy to fashion photography," Coddington says. Indeed, the eye doesn't linger on the dress' fanciful floral print or even on Kebede's lyrical features. Instead, Elgort captures the pleasures of fashion through the light-hearted curiosity of childhood.

Robin Givhan is a special correspondent for style and culture for Newsweek and The Daily Beast. In 1995 she became the fashion editor of The Washington Post where she covered the news, trends and business of the international fashion industry. She contributed to Runway Madness, No Sweat: Fashion, Free Trade and the Rights of Garment Workers, and Thirty Ways of Looking at Hillary: Reflections by Women Writers . She is the author, along with The Washington Post photo staff, of Michelle: Her First Year as First Lady . In 2006, she won the Pulitzer Prize in criticism for her fashion coverage. She lives and works in Washington, D.C.