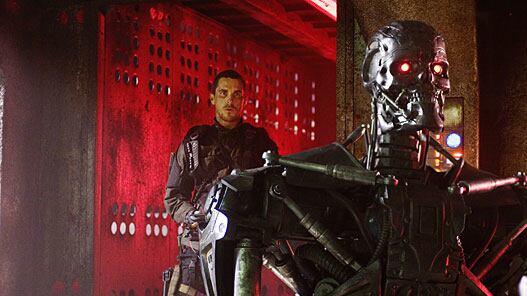

Terminator Salvation is set in the absurdly close year of 2018, when faceless machines dominate a post-apocalyptic, Mad Max landscape and a small band of humans—including Christian Bale as redemptive John Connor, the other J.C.—fights back.

In our worst nightmares, no one thinks this is where we’ll be in nine years. But deep into this latest installment of the money-minting, man vs. cyborg franchise, Connor says something that jolts us out of the fantasy and back to political reality. Ordered to attack a crucial enemy stronghold where humans will be collateral damage, he refuses, saying, “If we attack tonight, we lose our humanity.”

The filmmakers don’t have to plant any political reminders; they are inevitable given the battle-scarred world on-screen and off, and the mental baggage we carry to the movies.

Suddenly, we realize that the essential question of Terminator Salvation is not so obscure, but one hovering all around us today: What does it mean to be humane in a time of war? That question is almost as easily buried in life as it is in the film, lost amid self-serving political dogfights and legitimate subjects like the legal definition of torture. And really, sometimes it takes a popcorn movie to cut through the rhetoric around a hot-button issue. At what point do we lose our humanity? When we attack? Deprive prisoners of sleep? Waterboard?

Not every escapist action flick has such moments of political resonance. There are none at all in the new Star Trek. They are everywhere in the other Christian Bale action franchise, Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies. In Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, Gotham pointedly becomes a grimmer version of post-9/11 New York, terrorized by sinister forces. That echo of a still-present tension—could it happen again?—is partly what gives these films artistic cred and extends their audience to people who might not ordinarily want to see a Batman flick. Not as oblivious as Star Trek or as deliberate as Dark Knight, Terminator Salvation simply lets its relevance sneak up on us.

When the Terminator series started 25 years ago, it preyed on already distant fears of a too-mechanized society and nuclear Armageddon. It could afford to be campy. This new, fourth installment seems to carry us further than ever from current global politics, plopping us down post- Judgment Day and adding a survivalist plot so complicated by time travel that Connor meets a teenage version of his own father. However fantastic the details, though, Terminator Salvation takes place in a world permanently at war, and more than six years into the war with Iraq, that atmosphere feels familiar. The filmmakers don’t have to plant any political reminders; they are inevitable given the battle-scarred world on-screen and off, and the mental baggage we carry to the movies.

Sometimes it takes a popcorn movie to cut through the rhetoric around a hot-button issue.

The film would have been stronger if it had probed its moral questions instead of offering stock Hollywood answers about heroism and self-sacrifice. It’s not spoiling anything to say the movie, which is ultimately about the difference between men and machines, asks what it means to have a human brain and heart. It responds with a character who’s a little like the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz and a little like Frankenstein’s monster—that is, too much of a flat, unconvincing metaphor to carry much weight. But this is, after all, an action film, and the director, McG, keeps things moving without so much as a pause to develop characters (even the extraordinary Bale can’t add depth), much less ponder the ethics of war. Fair enough.

Reality intrudes anyway, in another moment that breaks through the escapist fantasy. As Connor battles the machines, he briefly confronts the Arnold Schwarzenegger Terminator from the first two movies, though the real Schwarzenegger did not take time out from playing governor of California to shoot these scenes (he’s got enough problems). Everything was done digitally, with the face of a younger Arnold attached to a double’s naked body, whose genital area is so obscured it’s already television-ready.

The simple joke of seeing Arnold come back shakes us out of the story. What lingers is the recognition of where all those popcorn movies took his career, of how powerfully and often unexpectedly movies and politics are linked. With its movie-star governor (here he really is the Governator) and the ethical question that insinuates itself and won’t let go, Terminator Salvation presents an apparently alien future that in some ways is already here.

Caryn James is a cultural critic for The Daily Beast. She also contributes to Marie Claire and The New York Times Book Review. She was a film critic, chief television critic and critic-at-large for The New York Times, and an editor at the Times Book Review. She is the author of the novels Glorie and What Caroline Knew.