Writing for the Forward, the translator and journalist Hillel Halkin argues that settlements are no obstacles to peace. If a two-state solution is reached, he reasons, most settlers will be incorporated into sovereign Israel, and the rest ought to be able to live in Palestine. No need to uproot anybody—so what’s the big deal?

I’m reminded of the Talmudic distinction between the law b’dieved (after the fact) and l’chatchila (before the fact). That’s because Halkin conflates two very different questions: b’dieved, since we have more than 500,000 Jews living in the Occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, what are we going to do with them? And l’chatchila, should Israel build and support new settlements and expansion of existing ones?

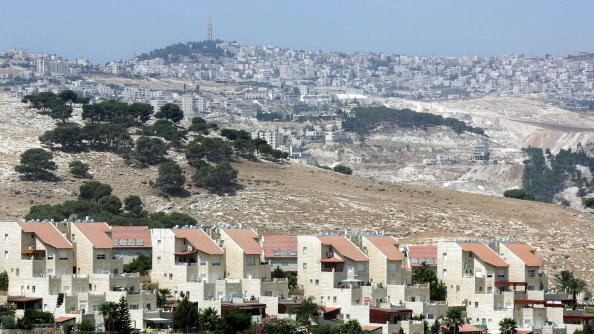

The first question, to my mind, is indeed thorny. On the one hand, I, like Halkin, love the bare Judean hills and want Jews living in Hebron, near the cave where Abraham and Sarah are buried. On the other hand, I cannot write off the costs of existing settlements as he does. First, even the big blocs (like Gush Etzion and Maale Adumim), which “everyone agrees” will be incorporated into Israel in a future deal, make negotiating such a deal tougher. Why? Because for every acre of land beyond the pre-1967 borders Israel annexes, it will likely have to give the Palestinians an acre inside its sovereign borders. As former American negotiator Robert Malley observed in 2001, the Camp David negotiations failed in part over Israel’s unwillingness to provide one to one land swaps. Nor is it hard to see why—after Palestinian leaders have restricted their ambitions to the Occupied West Bank and Gaza, and after they’ve agreed to swap land they are sure is rightfully theirs, can they be expected to offer those swaps at a discount? But that land has to come from somewhere, and as Israel develops the land just inside the Green Line (as well it should), the reservoir shrinks. So the lovely suburb of Efrat comes at a cost, and one that is getting harder to pay.

But it’s not just this “land debt” that causes trouble. Current settlements also impede peace because they make the daily life of Palestinians harder, hardening attitudes towards Israel and breeding resentment. Take water: Amnesty International reports that in 2009, settlers used as much water as all their Palestinian neighbors, though there are more than four times as many Palestinians as Jews in the West Bank. Meanwhile, Palestinians survive on bare minimum amounts, and the Israeli Civil Administration routinely destroys their cisterns and wells (with the express goal of containing the Palestinian population). And settlers don’t just consume resources. As a report by the Jerusalem Fund documents, some of them also attack Palestinians (in more than 2000 incidents between 2009 and 2011, when West Bank Palestinian violence against Israelis had slowed to a trickle). Remember how the second intifada eroded Israeli sympathy for Palestinians: How do we expect Palestinians to react any differently to arson, vehicular assault, and the like?

But let’s grant Halkin that, despite problems like these, we’re stuck with settlers in the West Bank. Let’s ignore the fact that a good portion of those settlements were built on private Palestinian land or landed dubiously seized by the Israeli army. Suppose we buy all his arguments about how painful disengagement was (though, for my money, the only Israelis still talking about 2005 are Religious Zionists, who largely reject negotiation anyway). We’d still have to ask the far more important, and frankly, simpler, question, which Halkin ignores: l’chatchila (before the fact), knowing all this, why on earth would Israel build more settlements?

Why, in July 2012, would the Netanyahu government subsidize 50-70 percent of the cost of new developments in more than 70 West Bank settlements (many of them, according to Haaretz, “deep inside the West Bank in areas that Israel would likely have to evacuate to make way for a Palestinian state”)? Why does the Ministry of Education subsidize teachers in the West Bank, and why does the Ministry of Finance give settlers a 7 percent tax break? Why does Tekoa Dalet, a settlement that’s illegal even by Israeli law, have beautiful flattop roads and functioning utilities? Why is the rent there ridiculously low?

When lefties like me complain, “settlements are an obstacle to peace,” we don’t just mean those already existing. We’re saying that new settlements are constantly making things worse. We’re wondering who benefits when the settler population grows by 15,000 in 2012. We’re wondering what right-wing politician Yaakov Katz meant when, predicting that the Israeli settler population would reach one million in four years, he told the Guardian that then, “the revolution will have been completed.” Actually, I have a hunch about that: Katz is, after all, glad Israelis “decided to vote against the two-state solution” because “we were granted Divine rights to this land.” Here’s what we’re really wondering: why does a moderate like Halkin advance arguments that help Katz and his ilk gut Israel’s chances of making peace?