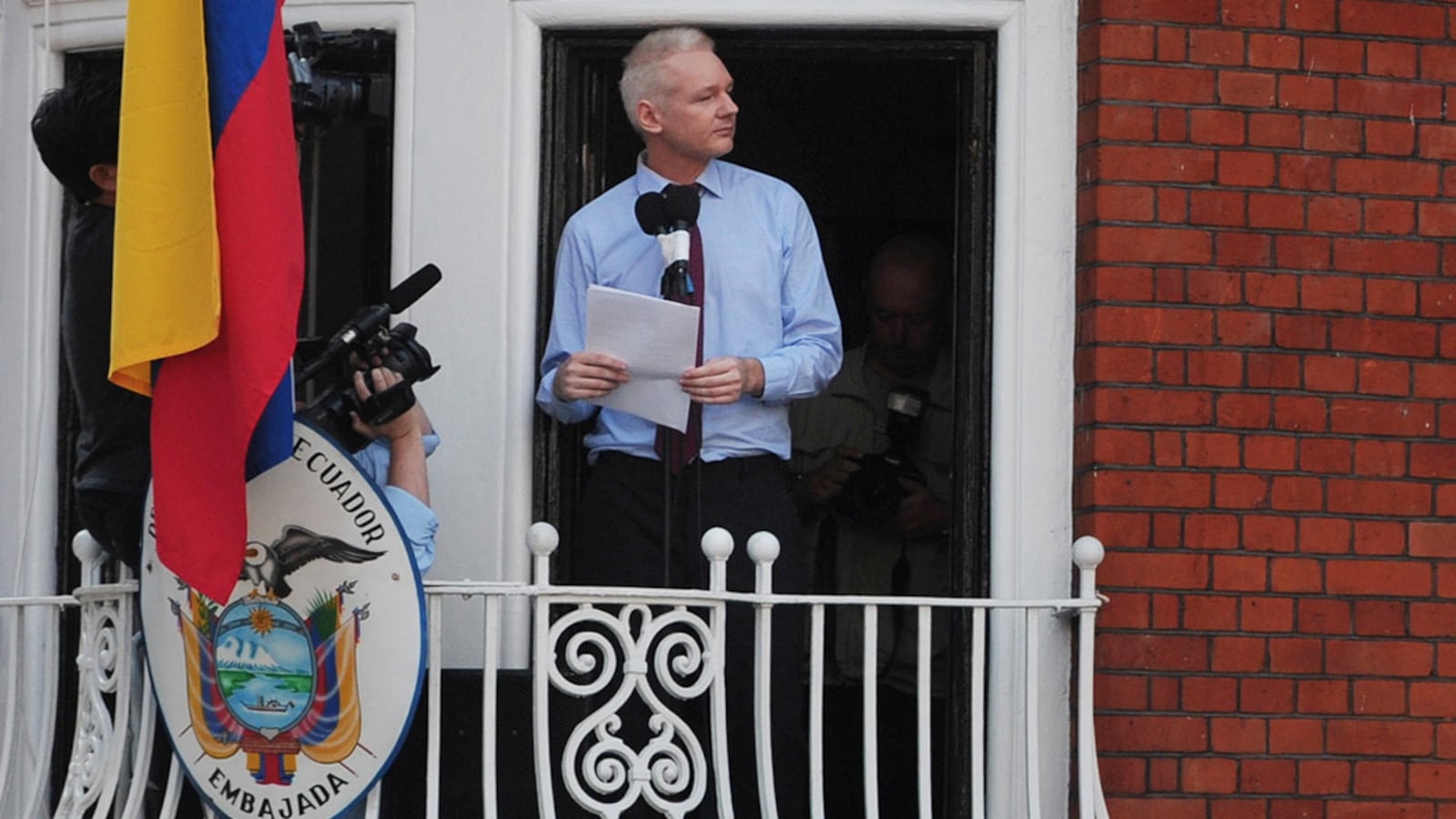

Dressed in a light blue shirt and red tie, his trademark white hair cropped short, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange dramatically stepped into the world’s spotlight again today, addressing supporters—and the global media—from a small balcony on the first floor of the Ecuadoran Embassy in London’s plush Knightsbridge district.

This was Assange’s first public appearance since he took refuge in the embassy two months ago, having failed in a protracted appeal against extradition to Sweden on allegations of sexual assault. Assange, 41, thanked his supporters, who numbered several hundred held behind a police cordon, for keeping their “vigil in the night.” In quasi-religious language, he described last Thursday, when Ecuador granted him political asylum. “The sun came up on a courageous Latin American country that took a stand for justice,” he said.

Assange has often shown a firm grasp of the theatrical. While still on bail last fall, he turned up at a the temporary London Occupy movement camp outside St Paul’s Cathedral in a V for Vendetta mask; he has since received the support of much (though not all) of the global Occupy movement. This afternoon’s speech reached more broadly for Latin American populism. In the run-up to his appearance, many wags had been making analogies between Assange’s balcony appearance and the “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” moment of Eva Perón in the musical Evita. The link is not as spurious as it may seem: as Mac Margolis describes in this week’s edition of Newsweek, Ecuadoran President Rafael Correa follows in the traditions of his predecessor Jose Maria Velasco, who once said: “Give me a balcony, and I’ll become the next president.”

While praising Ecuador and the other members of the Organization of American States that have agreed to debate the issue (despite vetoes from Canada and the U.S.) Friday in Washington, D.C., Assange also tried to politicize his case into a wider issue of press freedom and state repression. While he briefly mentioned the Pussy Riot trial, which saw three Russian singers jailed for two years for an anti-Putin concert in a church, his main focus was on the U.S. In ever more apocalyptic language Assange asked if America would use the opportunity “to affirm the revolutionary values it was founded on ... Or will it lurch off the precipice, dragging us all into a dangerous and oppressive world in which journalists fall silent under the fear of prosecution and citizens must whisper in the dark?”

In the most effective part of his speech, Assange turned the issue away from himself and focused on the case of Bradley Manning, the U.S. Marine who allegedly leaked the diplomatic cables that brought WikiLeaks to global prominence. He called on President Obama to “renounce the witch hunt against WikiLeaks.”

“The war on whistleblowers must end,” said Assange, who questioned Manning’s treatment in jail for the last two years and called for his immediate release: “He is hero and an example to all of us ... one the world’s foremost political prisoners.”

While many civil libertarians and activists may have doubts about Assange’s case—especially since the charges he could face in Sweden are hardly “political”—the Manning cause does garner broader support. By fusing that kind of domestic dissent with President Correa’s apparent desire to become a new Latin American leader (now that Fidel Castro is retired and Hugo Chávez is recovering from cancer), Assange is attempting to turn his “hacktivism” into something bigger. Already, with the use of his face on T-shirts and placards, Assange is beginning to resemble some latter-day digital Che Guevara.

By his energy and demeanor, Assange appeared to enjoy his moment in the unnaturally hot London sun. How long it will last when the reality of his predicament grinds out over the weeks and months ahead remains to be seen. Sweden’s record on civil liberties, press freedom, and treatment of prisoners remains far superior to Ecuador’s, and though Assange’s lawyer Baltasar Garzón denied knowledge of it in an statement earlier today, there are reported moves to heal the diplomatic rift between Sweden and Ecuador, with a guarantee by the former that it won’t let Assange be extradited to the U.S.

Meanwhile, many of those who support WikiLeaks and press transparency have severe doubts about Assange’s claim to be a spokesman for whistleblowers across the world. Heather Brooke, the campaigning journalist who collaborated with Assange in The Guardian’s publication of redacted U.S diplomatic cables, told The Daily Beast today: “Free speech for him, yes, but when it comes to other people’s free speech—especially about him—Assange believes in Stalinist levels of control.” Brooke, who spent years campaigning to expose an M.P. expense scandal in the U.K., added: “One can very much judge the man by the friends he keeps, and the president of Ecuador is no friend of free speech.”

So while Assange’s balcony scene clearly appealed to his supporters, the realities waiting in the wings won’t go away.