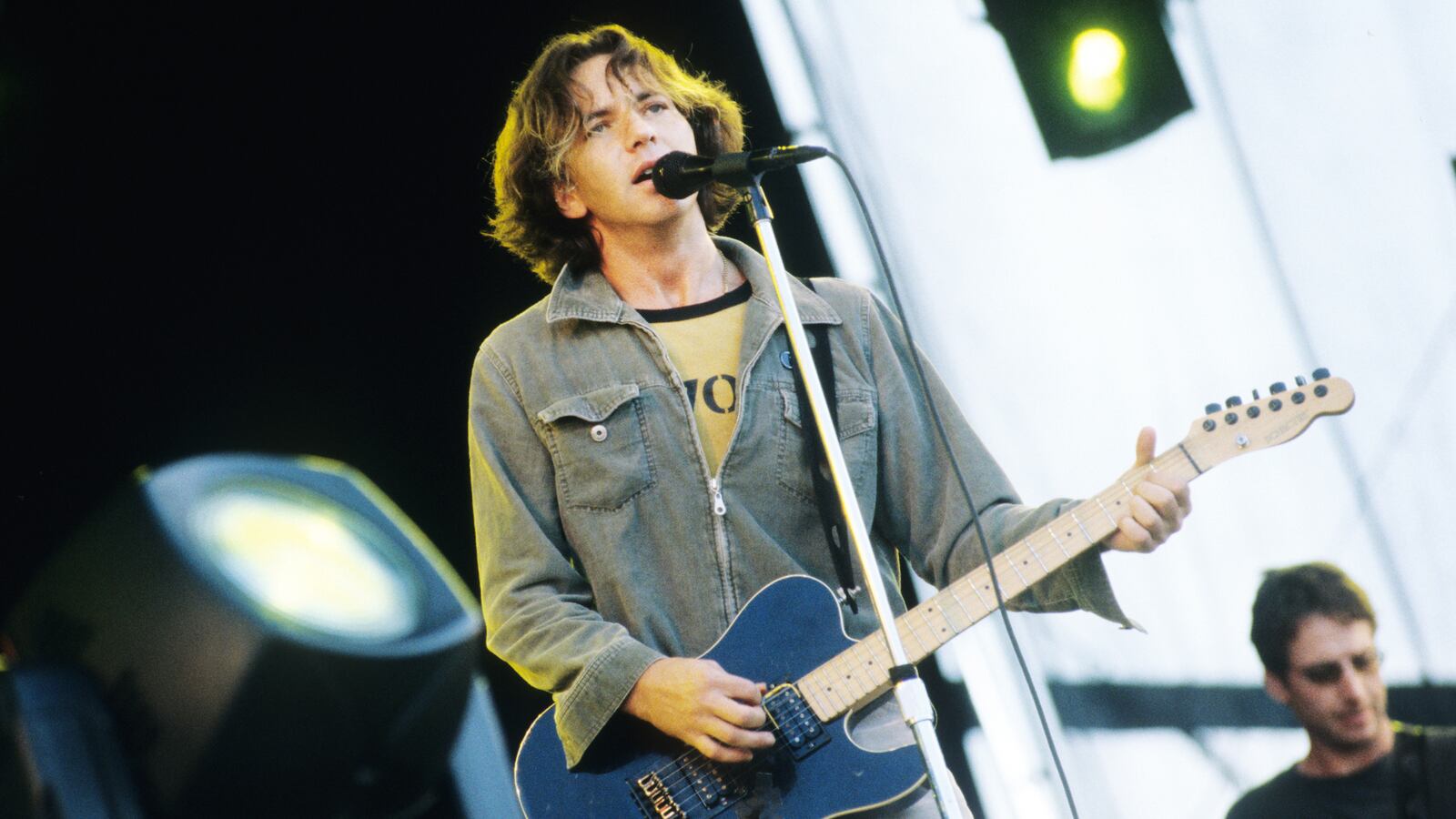

At a 2000 European music festival, nine people were killed after a crowd stampede that occurred while the band Pearl Jam performed.

A day of rain had soaked the grounds of the Roskilde Festival in Denmark to mud. After vendors had run out of boots, concertgoers began wrapping plastic bags around their shoes. That made it difficult to navigate the pavement at the Orange Stage, where an estimated 50,000 fans had turned up to see the Seattle rockers perform.

Before Pearl Jam began playing, audience members pushed to get close to the stage. The surge only became more aggressive once the music started, perhaps because of sound issues with speakers further back, according to accounts given to Rolling Stone at the time.

As the mosh pit intensified, security guards noticed that things were more intense than usual. Something seemed off.

One guard, named Per Johansen, was stationed by the pit near the crowd barrier, his job to hurl fans out of the crowd to safety if they surfed to the edge or got caught in a violent melee. “There were some girls, and they were extremely difficult to pull up,” he told the magazine, recounting how he knew things were wrong. “Usually we have one guy to pull one up. But we needed two.”

Eventually the maelstrom of moshing in such a tight crowd formed an actual pit. As people were being crushed, they began to fall to the ground, where they were trampled, stood on, and unable to get back up. “Arms, legs and heads were getting caught in a lethal tangle,” the magazine said. “At the bottom of that human hole, about seven feet in diameter, was a pile of bodies.”

About 45 minutes into the set, security escalated concerns up the chain, eventually reaching Pearl Jam’s manager and then frontman Eddie Vedder, who stopped the music.

“What will happen in the next five minutes has nothing to do with music,” he said to the crowd. “But it is important. Imagine that I am your friend and that you must step back so as not to hurt me. You all have friends up front. I will now count to three, and you will all take three steps back. All who agree say ‘Yes’ now.”

Eight men died that night of asphyxiation. A ninth succumbed to injuries five days later. It was one of the deadliest events in rock music history, 21 years after 11 people died in a stampede at a 1979 The Who concert in Cincinnati.

What happened during Pearl Jam’s set in 2000 has been brought up frequently in recent days, following the tragedy in Houston.

Eight died and at least 25 were injured following a violent and dangerous crowd surge during hip-hop star Travis Scott’s performance at the Astroworld Festival Friday night, the incident now also joining the ranks of worst death tolls ever at a music event.

The comparisons between the two events are haunting and uncanny. But, at a time of unanswered questions and a reckoning over just how inescapably dangerous music festivals may be, the Pearl Jam incident of two decades ago provides, at the very least, a litany of lessons—not to mention a roadmap for how an artist implicated in such a calamity and festival organizers can work together to ensure safety going forward.

In the aftermath of the Astroworld disaster, investigations have been launched and speculation has been sparked about why this happened, how it could have been prevented, and who is to blame.

The latter question has stoked a finger-pointing battle: the aggressive, safety-thwarting concertgoers; festival organizer Live Nation; local officials and possibly ill-equipped, understaffed security and medical teams; or Scott himself.

The star has a history of inciting chaos, having twice faced criminal charges for encouraging fans to breach barricades and thwart security, and a video recently resurfaced of him in 2015 telling a crowd to “fuck up” a fan who stole his shoe. Those fans, though, have relished the rebellious energy of his shows, reveling in lyrics like “it ain’t a mosh pit if ain’t no injuries” from 2018’s “Stargazing.”

During the deadly unrest on Friday night, Scott paused his performance as an ambulance moved through the crowd, before cajoling the crowd to “make this motherfucking ground shake” as he finished his set. Videos from the festival have gone viral revealing the lengths fans went to try to get security’s attention as the situation escalated, climbing scaffolding to plead with camera operators and leading chants of “stop the show.”

People have wondered whether there was adequate crowd control and security. Some have questioned why the concert wasn’t halted at the first sign of unrest—officials have since said they feared a riot if they abruptly stopped the show—and what emergency protocols were in place in case of a situation like this. Several lawsuits have already been filed against Scott, Live Nation, ScoreMore, and other parties involved with the festival.

Beyond blame is the question of actual safety at music festivals—a concert experience that has led to mass death tolls once a decade since the Pearl Jam incident in 2000. (In 2010, 21 people died in Germany at the Love Parade Festival due to overcrowding of an access tunnel.) Since 2006, 750 injuries and 200 deaths have been linked to events produced by Live Nation, according to the Houston Chronicle.

As this is once again debated in the wake of the Astroworld tragedy, it’s prudent to look back at how the parties involved reacted following that tragedy two decades ago.

A complete rethinking of festival safety took place after what happened at Roskilde. A new set of best practices developed in collaboration with festival organizers, independent security teams and advisors, and the artists themselves were widely enacted across Europe, setting a standard for music-festival safety that has yet to make its way back over the pond, which has failed to adopt stricter crowd-management measures.

Among the changes are paved surfaces, better security training, and smaller, separated, and cordoned-off zones to mitigate dangerous overcrowding and prevent the kind of rush forward that leads to audience members being crushed or trampled by those behind them. Not only are there limits to how many people can be directly in front of the stage, there must be multiple, cleared channels through the audience that are wide enough for ambulances to pass through. Video from Astroworld showing an ambulance struggling to part the sea of crowded Scott fans is a testament to the necessity of this.

These separate zones and channels also reduce the risk of overzealous crowd-surfing, a practice long-ubiquitous in the States that would allow a reveler to coast across an entire festival site with no safety net unless they happen to reach a barrier at the edge of crowd where a security official rescues them.

A Danish crowd-safety expert told Texas Monthly that he was shocked that Scott’s set continued for 37 minutes after Houston police reportedly declared the festival a “mass casualty event.”

In Europe, he explained, CCTV is used so that festival organizers and security teams can monitor the crowd for disruptions and emergencies, with many European festivals empowering a security manager of an independent team to stop a show immediately. The sound cuts off. Lights go on. The artist performing or another official would instruct the crowd on what is happening in order to prevent the riots that Houston police were concerned about.

Fans lay down flowers in Roskilde, 30 kilometers west of Copenhagen on Saturday July 1, 2000, where eight fans were trampled to death late June 30. The disaster occurred when the crowd surged toward the stage during a performance by Pearl Jam. A further 26 people needed hospital treatment.

ReutersWhat happened at Roskilde spurred discussion across Europe about how to revamp safety measures and make them stricter. But it also, with Pearl Jam’s involvement, advanced the idea of artists’ investment in enforcing those protocols.

At future festivals where they were booked, they required organizers to meet certain safety stipulations in advance and, according to the entertainment news website Uproxx, evaluated “all operational and security policies in advance, such as design and configuration of barriers and security response procedures in relation to ensuring… safety.”

At the top of the checklist is a full rundown of the festival’s plan for stopping the show, including the mechanisms for communicating an emergency situation to the band on stage and how long that would take, a failure that they believe cost lives at Roskilde. The evaluation also includes, “checking out the festival security’s command center, location and effectiveness of said locations of EMTs, barricade types, placement and configuration, how alcohol would be sold, the venue’s capacity and ‘entry and transition procedures,’” Uproxx wrote.

People attend a makeshift memorial on November 7, 2021, at the NRG Park grounds where eight people died in a crowd surge at the Astroworld Festival in Houston, Texas.

Thomas Shea/AFP/GettyThe question of artist blame in an event like this is a murky one, and equally complicated is what the responsibility is in the aftermath, particularly when it comes to the victims and what they’re owed.

Pearl Jam became proactive in reforming music festivals to make them safer and have been vocal in the years since about the devastation that night caused, even becoming close to the families of the victims in order to find a way to heal together.

Scott has announced that Astroworld attendees will receive refunds, and he has pulled out of an upcoming festival in Las Vegas. He has also pledged to cover funeral costs of those who were killed. Still, there is debate over whether that is enough. Some Spotify users have urged a boycott of his music, for example, as the question of what accountability means in this situation is debated.

Is there something to be learned from all of this? Of course. By all accounts, it was preventable. It’s whether something will be learned that is now the pressing issue.