Lou Gehrig, in his quiet, methodical, all but invisible way, was having a fantastic year. As the second week of September began, he had 45 home runs, 161 runs batted in, and a .389 batting average. As his biographer Jonathan Eig notes in Luckiest Man, Gehrig could have stopped there, with almost a month of the season still to play, and had one of the best seasons ever. In fact, he did essentially stop there.

His mother was unwell with a goiter and needed surgery. Gehrig was beside himself with anxiety. “I’m so worried about Mom that I can’t see straight,” he confided to a teammate.

“All his thoughts were on Mom,” the sportswriter Fred Lieb wrote later. “As soon as he finished the game, he would rush to the hospital and stay with her until her bedtime.” Gehrig hit just two more home runs the rest of the season. His heart wasn’t in the game. All he could think about was his beloved momma.

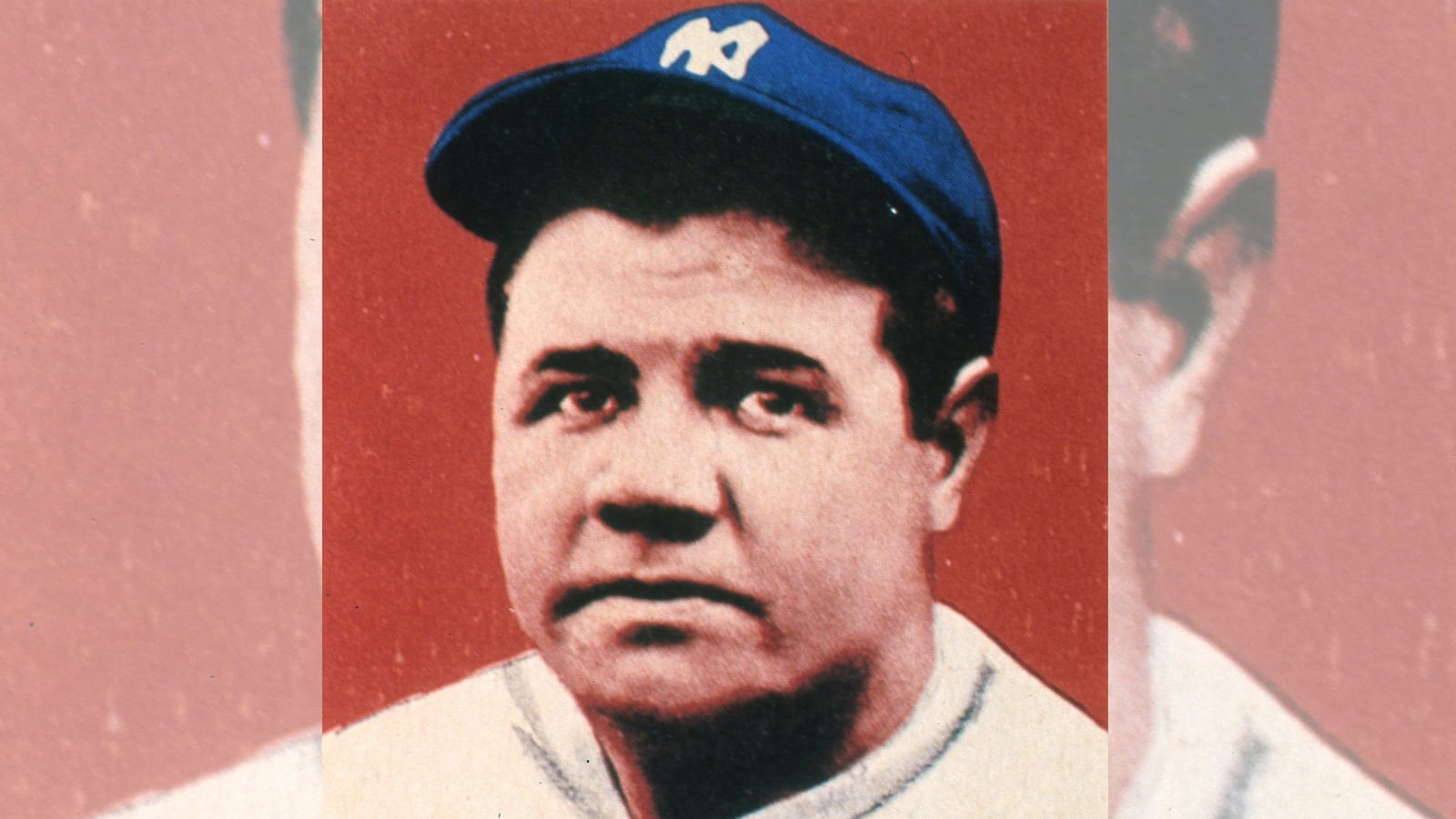

Babe Ruth, meanwhile, began knocking balls out of parks as if hitting tee shots at a driving range. Between September 2 and 29, he hit 17 home runs. No one had ever done anything like that in a single month.

The Yankees seemed incapable of doing anything wrong. On September 10, they beat St. Louis for the twenty-first time in a row—the most consecutive victories by one team over another during a season.

On September 16, Wilcy Moore, who was such a bad batter that players would come out of the locker room and vendors would pause in their transactions to watch the extraordinary sight of him flailing at empty air with a piece of wood, miraculously connected with a ball and sent it over the right field wall for a home run, an event that nearly gave Babe Ruth a heart attack. On the mound, Moore scattered 7 hits to push his record to 18 and 7 as the Yanks beat the White Sox 7–2.

In the midst of this, almost unnoticed, the Yankees clinched the pennant. They had been in first place every day of the season—the first time that had ever happened. Their position was so commanding that they could lose all 15 of their remaining games and the second-place A’s could win all 17 of theirs, and the Yankees would still come out on top. In point of fact, the Yankees won 12 of their last 15 games even though they didn’t need to. They couldn’t help themselves.

Ruth was majestically imperturbable. On September 16 he was called into court in Manhattan, charged with the alarming crime of punching a cripple. The reputed victim, Bernard Neimeyer, claimed that on the evening of July 4 he had been walking near the Ansonia Hotel when a man accompanied by two women accused him of making an inappropriate remark and punched him hard in the face. Neimeyer said he didn’t recognize his assailant, but was told by onlookers that it was Babe Ruth. Ruth, in his defense, said that he had been having dinner with friends at the time, and produced two witnesses in corroboration. In court, Nei- meyer seemed to be a little crazy. The Times reported that he frequently “rose excitedly to his feet, waving a book of notes which he added to from time to time as the hearing proceeded. He was often cautioned by the clerk of the court not to talk so loudly.” The judge dismissed the case to general applause. Ruth signed a bunch of autographs, then went to the ballpark and hit a home run, his 53rd.

Two days later, in a doubleheader against the White Sox, he socked his 54th, a two-run shot in the fifth inning. Three days after that, on September 21, Ruth came to the plate in the bottom of the ninth inning against Detroit. The bases were empty and the Tigers were up 6–0, so Sam Gibson, the Tigers’ pitcher, didn’t need to throw him anything good, and dutifully endeavored not to. Ruth caught one anyway, and hefted it deep into the right field stands for his 55th homer. A new record was beginning to seem entirely possible.

The next day Ruth hit one of his most splendid home runs of the season. In the bottom of the ninth inning, with Mark Koenig on third and the Yankees trailing 7–6, Ruth came to the plate and lofted his 56th home run high into the right field bleachers for a walk-off 8–7 victory. As Ruth trotted around the bases—carrying his bat with him, as he often did, to make sure nobody ran off with it—a boy of about ten rushed in from right field and joined him on the base paths. The boy grabbed onto the bat with both hands and was essentially carried around the bases and into the dugout, where Ruth quickly vanished down the runway, pursued by yet more jubilant fans. The game was the Yankees 105th victory of the season, tying the American League record for season victories.

Sports fans turned their attention to baseball and the question of whether Babe Ruth could break his home run record. It was getting awfully close. Ruth went two games, on September 24 and 25, without a homer, which left him four short of the record with just four games to play.

On the first of those four games, on September 27, Ruth got his 57th in style by hitting a grand slam off Lefty Grove of Philadelphia—one of only six home runs Grove gave up all season. Ruth didn’t hit grand slams often: this was his first of the season and only the sixth of his career.

The Yankees had a day off on September 28, and the rest clearly did Ruth good, for in his first at-bat the next day, in the start of a three-game series against the Washington Senators, he hit his 58th home run off Horace “Hod” Lisenbee, a rookie who was having a great year—the only good one he would ever have. Like Lefty Grove, Lisenbee gave up just six home runs all season. Two of them were by Ruth.

Ruth now needed just one more to tie his record. In the bottom of the fifth inning, Ruth came to the plate with the bases loaded and two out. Senators manager Bucky Harris signaled to the bullpen to send in a right-hander named Paul Hopkins.

Hopkins was an unexpected choice, and no doubt caused many a spectator to turn to the nearest person with a scorecard for enlightenment. Hopkins had just graduated from Colgate University and had never pitched in the major leagues before. Now he was about to make his debut in Yankee Stadium against Babe Ruth with the bases loaded and Ruth trying to tie his own record for most home runs in a season.

Pitching carefully (as you might expect), Hopkins worked the count to 3 and 2, then tried to sneak a slow curve past Ruth. It was an outstanding pitch. “It was so slow,” Hopkins recalled for Sports Illustrated seventy years later at the age of ninety-four, “that Ruth started to swing and then hesitated, hitched on it and brought the bat back. And then he swung, breaking his wrists as he came through it. What a great eye he had! He hit it at the right second—put everything behind it. I can still hear the crack of the bat. I can still see the swing.” It was Ruth’s 59th home run, tying a record that less than a month before had seemed hopelessly out of reach.

The ball floated over the head of the right fielder, thirty-seven-year-old Sam Rice, who is largely forgotten now but was one of the great players of his day and also one of the most mysterious, for he had come to major league baseball seemingly from out of nowhere.

Fifteen years earlier, Rice had been a promising youngster in his first season in professional baseball with a minor league team in Galesburg, Illinois. While he was away for the summer, his wife moved with their two small children onto his parents’ farm near Donovan, Indiana. In late April, a tornado struck near Donovan, killing seventy-five people. Among the victims were Rice’s wife, children, mother, and two sisters. Rice’s father, himself seriously injured, was found wandering in shock with one of the dead children in his arms; he died nine days later in the hospital. So, at a stroke, Rice lost his entire family. Dazed with grief, Rice drifted around America working at odd jobs. Eventually he enlisted in the navy. While playing for a navy team his remarkable talents became apparent. Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, somehow heard of this, invited him for a trial, and was impressed enough to sign him. Rice joined the Senators and in his thirties became one of the finest players in baseball. No one anywhere knew of his personal tragedy.

After Ruth’s homer, Hopkins struck out Lou Gehrig to end the inning, then retired to the bench and burst into tears, overcome by the emotion of it all. Hopkins’s appearance was one of just eleven he made in the majors. He missed the whole of the 1928 season with an injury and retired with a record of no wins and one loss after the 1929 season. He returned to his home state of Connecticut, became a successful banker, and lived to be ninety-nine.

The last day of September was sultry in New York. The temperature was in the low 80s and the air muggy when, in the next-to-last game of the season, Ruth came to the plate in the bottom of the eighth against Tom Zachary, a thirty-one-year-old left-hander from a tobacco farm in North Carolina. Though a pious Quaker, Zachary was not without guile. One of his tricks was to cover the pitching rubber with dirt so that he could move closer to home plate—sometimes by as much as two feet, it has been claimed. In 1927 he was in his tenth season. He gave up just six home runs all year. Three of them were to Ruth.

It was Ruth’s fourth trip of the day to the plate. He had walked once and singled twice and had come nowhere near a home run. The score was tied 2–2. There was one out and one man on—Mark Koenig, who had tripled.

“Everybody knew he was out for the record, so he wasn’t going to get anything good from me,” Zachary told a reporter in 1961. Zachary wound up, eyed the runner, then uncorked a sizzling fastball. It went for a called strike. Zachary wound up and threw again. This pitch was high and away, and Ruth took it for a ball. For his third pitch, Zachary threw a curve—“as good as I had,” he recalled—that was low and outside. Ruth hit the ball with what was effectively a golf swing, lofting it high into the air in the direction of the right field foul pole. The eight thousand fans in Yankee Stadium watched in silence as the ball climbed to a towering height, then fell for ages and dropped into the bleachers just inches fair. Zachary threw down his glove in frustration. The crowd roared with pleasure.

Ruth trotted around the bases with his curiously clipped and delicate gait, like someone trying to tiptoe at speed, then stepped out of the dugout to acknowledge the applause with a succession of snappy military salutes. Ruth was responsible for all four runs that day. The Times the next day referred to the score as “Ruth 4, Senators 2.”

A little-known fact was that the game in which Babe Ruth hit his 60th home run was also the last game in the majors for Walter Johnson, the greatest pitcher of the age. No one threw harder. Jimmy Dykes, then of the Athletics, recalled in later years how as a rookie he was sent to the plate against Johnson, and never saw Johnson’s first two pitches. He just heard them hit the catcher’s mitt. After the third pitch the umpire told him to take first base.

“Why?” asked Dykes.

“You’ve been hit,” explained the umpire.

“Are you sure?” asked Dykes.

The umpire told him to check his hat. Dykes reached up and discovered that the cap was facing sideways from where Johnson’s last pitch had spun the bill. He dropped his bat and hurried gratefully to first base.

In twenty-one years as a pitcher, Johnson gave up only ninety-seven home runs. When Ruth homered off Johnson in 1920, it was the first home run anyone had hit off him in almost two years. In 1927, Johnson broke his leg in spring training when hit by a line drive, and never fully recovered. Now, with his fortieth birthday approaching, he decided it was time to retire. In the top of the ninth inning, in his last appearance in professional baseball, he was sent in to pinch-hit for Zachary. He hit a fly to right field. The ball was caught by Ruth, to end the game, Johnson’s career, and an important part of a glorious era.

In the clubhouse afterward, Ruth was naturally exultant over his 60th homer. “Let’s see some son of a bitch try and top that one!” he kept saying.

The general reaction among his teammates was congratulatory and warm, but in retrospect surprisingly muted. “There wasn’t the excitement you’d imagine,” Pete Sheehy, the team equipment manager, recalled many years later. No one expected Ruth to stop at 60. It was assumed that he would hit at least one more the next day, and possibly reach even greater heights in years to come. Ruth after all had been the first to hit 30, 40, 50, and 60 homers. Who knew that he wouldn’t hit 70 in 1928?

In fact, neither he nor anyone else would hit so many again for a very long time. In his last game of the season, Ruth rather anticlimactically went 0-for-3 with a walk. In his last at-bat he struck out. Lou Gehrig, however, did hit a home run, his 47th of the season. That might seem a disappointing number after his earlier pace, so it is worth remembering that it was more than any other player had ever hit, apart from Ruth.

In banging out 60 home runs, Ruth out-homered all major league teams except the Cardinals, Cubs, and Giants. He hit home runs in every park in the American League and hit more on the road than at home. (The tally was 32 to 28.) He homered off thirty-three different pitchers. At least two of his home runs were the longest ever seen in the parks in which they were hit. Ruth hit a home run once every 11.8 times at bat. He had at least 6 home runs against every team in the American League. He did all this and still batted .356—and scored 158 runs, had 164 runs bat- ted in, 138 walks, 7 stolen bases, and 14 sacrifice bunts. It would be hard to imagine a more extraordinary year.

Ruth and Gehrig between them came first and second in home runs, runs batted in, slugging percentage, runs scored, total bases, extra base hits, and bases on balls. Combs and Gehrig were first and second in total hits and triples. Four players—Ruth, Gehrig, Lazzeri, and Meusel—each had more than 100 runs batted in. Combs was also third in runs scored and total bases, and Lazzeri was third in home runs. As a team, the Yankees had the American League’s highest team batting average and lowest earned-run average. They averaged 6.3 runs per game and almost 11 hits. Their 911 runs were more than any American League team had ever scored in a season before. Their 110 victories were a league record, too. Just one player was ejected from a game all season, and the team had no fights with other teams. Baseball has never fielded a more complete, dominant, and disciplined team. also of the Yankees, hit 61, though Maris had the advantage of a longer season, which gave him 10 more games and 50 more at-bats than Ruth in 1927. In the 1990s, many baseball players suddenly became immensely strong—some evolved whole new body shapes—and began to smack home runs in quantities that made a mockery of Ruth’s and Maris’s numbers. It turned out that a great many of this new generation of ballplayers—something in the region of 5 to 7 percent, according to random drug tests introduced, very belatedly, in 2003—were taking anabolic steroids. The use of drugs as an aid to hitting is far beyond the scope of this book, so let us just note in passing that even with the benefit of steroids most modern players still couldn’t hit as many home runs as Babe Ruth hit on hot dogs.

It was one hell of a summer.