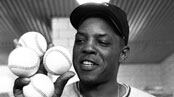

Nearly half of the youthful memories I have of my father involve time spent traveling to ballparks all over the country to see Willie Mays play. From the old Polo Grounds in Coogan’s Bluff (Or was it Coogan’s Hollow? I was too young to remember anything but the experience of going to the game) to Cincinnati, San Francisco, and, finally, Atlanta, we saw Willie play in every National League park except the Astrodome (which my father rejected on moral grounds, meaning indoors and artificial turf). Reading James Hirsch’s mammoth (560 pages of text) Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, I could feel a large chunk of my life passing in front of me. You had to be there, or at least see some really good archival footage, to understand the excitement of that basket catch and followup sidearm throws, the lunging, sweeping swing, and the electrifying base-running in which he would round first base in a wide sweep, lose his cap, and slide into second before it hit the ground (or at least that’s the way I remember it).

“It’s tragic when one as popular as Willie Mays feels a contribution in race relations is measured by the clubs he belongs to or how many golf courses he is able to play.”

Hirsch’s book is assiduously researched and handsomely written. Here’s his account of Mays’ catch in the 1954 Series against the Cleveland Indians, possibly the most famous play in baseball history: “He ran past the farthest edge of the outfield grass, veering slightly to his right as his spikes touched the narrow cinder strip near the base of the wall. At the last moment, he looked up, extended his arms like a wide receiver, and opened his Rawlings Model HH glove. The ball fell gently inside. He had 10 feet to spare.” It was a catch which, in the words of Alf Van Hoose, a columnist for the morning paper in Mays’ native Birmingham, “had to be seen not to be believed.”

Mays was so much more than a great ballplayer—and it is arguable that he was the greatest all-around player ever—that it’s difficult to recapture the charge he put into baseball in the early '50s when, in 1951, he became the youngest black player to make the Majors. Swarms of veteran baseball writers—many of them, like Roger Kahn and Charles Einstein, from liberal Jewish backgrounds—idolized him. A white woman, a movie star, from Alabama, Tallulah Bankhead, took parties to the Polo Grounds to root for him. Mickey Mantle came to New York the same year and was of equal baseball talent as Willie, but he was mercilessly booed by fans of the crosstown rival Yankees for not being Joe DiMaggio while Mays was unconditionally worshipped.

“I don’t think any ballplayer,” New York’s leading columnist Red Smith wrote, “ever related to the fans as quickly as Willie.” Grantland Rice, the elder statesman of New York sportswriters, called him, “The kid everybody liked.”

He was photographed playing stickball in the streets of Harlem and had pop songs written about him. When the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, New York mourned and hissed at Bay Area fans who had the gall not to treat him with proper respect. “What a town,” someone wrote after the Soviet premier visited, “They cheer Khrushchev and boo Willie Mays.” No superstar ever seemed so accessible—so just plain knowable—to his fans. Yet, despite a shelf of ghostwritten memoirs and autobiographies, the truth, as Bill James once observed, is “We really don’t know Willie Mays.”

The real problem with Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend is Willie Mays, who authorized the book but doesn’t seem to be inside it. Unlike Hank Aaron, who began to open up to the press and fans as he closed in on Babe Ruth’s career home run record in the early '70s, Mays has receded in our cultural memory over the last 40 years. As an icon of black America, he long ago lost his luster to bolder and more provocative athletes such as Bill Russell, Jim Brown, and, of course, Muhammad Ali. The reclaiming of at least some of that stature would seem to be the motive in working with a biographer; Hirsch writes that “Over the years, many writers, agents, and publishers approached Willie Mays, seeking his cooperation on a biography, and Mays always said no.” It should be noted, though, that Mays worked on several collections of memoirs with the late Charles Einstein and with journalist Lou Sahadi in a 1988 book, Say Hey – The Autobiography of Willie Mays.

I wish I could say that Willie has succeeded. In place of an explanation as to why he failed to ever speak up during the entire civil-rights movement—a particularly disappointing decision, as Mays grew up just outside Birmingham—we’re given lame rationalizations, “In my own way, I believe I’m helping” (by addressing and helping kid’s groups) and “Everyone must do his own job in his own way.” Willie’s “way” is that he was contributing to integration by playing on previously segregated golf courses; he told a reporter in 1968, “I’m the first Negro to be a member of the Concordia Club [in the Bay Area] ... Now you know that wasn’t possible 10 years ago. And I haven’t done these things and gotten these things by ‘doing nothing.’” To which Jackie Robinson, who had done more than Mays to make it possible for Willie to play at those country clubs, quite reasonably replied, “It’s tragic when one as popular as Willie Mays feels a contribution in race relations is measured by the clubs he belongs to or how many golf courses he is able to play.”

Curt Flood, who sued Major League Baseball unsuccessfully in 1970 to gain free agency for professional baseball players, accurately assessed Mays’ attitude when he told me in a 1991 interview, “I respect Willie enormously, but the truth is that he has always seen the world in terms of his own good fortune.” Speaking of Flood, whose lawsuit eventually led, through intense collective bargaining, to free agency, Hirsch does no honor to Flood’s legacy when he writes that, “Mays wants to see players make as much money as possible” but “free agency... invited disruption for management while obliterating any pretense that the players were loyal to their teammates, their organizations, or their cities. They were not mercenaries whose only loyalty was to their checkbook.”

One wonders exactly how Willie thought players could “make as much money as possible” if they couldn’t act as free agents. More important, though, is Mays’ concept (or at least as expressed by Hirsch) of loyalty; if players before free agency were bound to one team for life (or at least until their team chose to trade or release them) one wonders precisely how loyalty entered into the deal. One might reasonably argue that loyalty only became part of the equation when a player was free to choose his teammates, organization, and city.

More disturbing is Hirsch’s contention that “Mays’ central point—that the demise of the reserve clause contributed to a freewheeling money culture, which has diminished the players’ devotion to the game, fed their conceit about their self-worth, and raised self-aggrandizement to an art form—stands as a reasonable critique of the modern game.” Say hey, what? Are Hirsch and Mays really under the illusion that the game was any less about money when players were making a top salary (like Willie) of $100,000 a year instead of several million? If Mays’ attitude “stands as a reasonable critique of the modern game” it is one that Major League Baseball team owners would heartily endorse.

Willie Mays, is, for the most part, an exciting ride that justifies its length and offers a definitive account of Mays’ life and on-the-field achievement. Sadly, though, it also suggests that San Francisco sportswriter Glenn Dickey was correct in his famous summary that Mays “sheds his greatness like a cloak when he leaves the playing field.” Which Willie Mays do you want to hold in your memory? In the words of Willie’s predecessor on the Birmingham Black Barons, Satchel Paige, “You pays your money and you takes your choice.”

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles, authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Allen Barra writes about sports for The Wall Street Journal and the Village Voice. He also writes about books for Salon.com, Bookforum, and The Washington Post. His latest book is Yogi Berra, Eternal Yankee.