It’s not easy being a dad—so much to live up to, so far to fall. Just ask the sons who write memoirs about them. Do fathers always get buried in print? Sometimes, sure, like in Geoffrey Wolff’s mercilessly unpleasant portrait of his old man in The Duke of Deception. But there are more than a few books that manage to strike a balance between honesty and cruelty, respect and disappointment, connection and yearning.

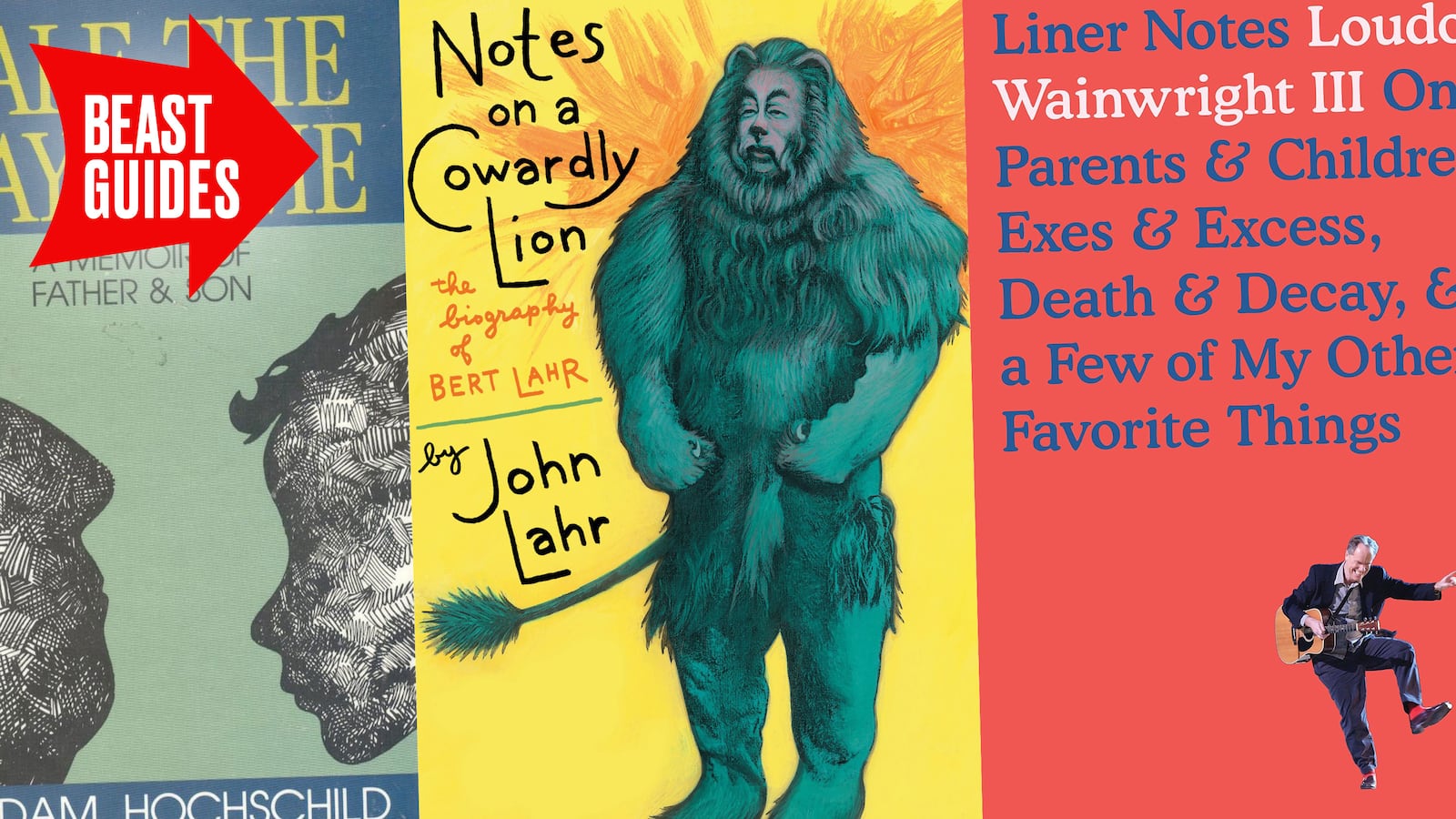

Just last year, in Liner Notes, Loudon Wainwright III, who’s made a career writing unapologetically intimate songs about his family, showed great restraint and admiration in his depiction of his father, who was an accomplished writer for LIFE magazine. He goes so far as to include a handful of his father’s original writing, an act of generosity that is surprising and revealing—his father was the better prose stylist. Maybe Wainwright is mellowing, but it suggests a trio of father-son memoirs where the writer has come to some kind of peace with the man he must love and kill and try to love again.

Notes on a Cowardly Lion by John Lahr

The first book written by the esteemed theater critic was about his father, Bert, most famous for his role as the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz. John was 28 when the book was published in 1969. The story is part-memoir, part biography, and part show business history. “Lahr was the last of America’s great comedians to graduate from burlesque,” the son writes, “leaving it late in 1922, just as burlesque was beginning to lose the brio that sparked its growth during the previous two decades.” Bert sailed through vaudeville, and for decades was a staple on Broadway. In the mid ’50s he starred in the original U.S. production of Waiting for Godot, and although he struggled to comprehend Beckett’s meaning, he was precisely the kind of old school performer that Beckett had in mind for his existential clowns. Bert was from the generation who thought of themselves as craftsmen, not artists. But his creative legacy is cemented in this admiring portrait. John clearly loves his dad, who was emotionally checked-out at home, but doesn’t shy away from laying bare the realities, the sadness and emptiness, of the performers’ life.

Half the Way Home by Adam Hochschild

This exquisite memoir by Adam Hochschild is a lesson in focus. It is about his relationship with his father and is remarkable for its delicacy and emotional power. It is one of those books where the reader is aware of how much is left out—anything extraneous. Hochschild, 43 when the book was published, grew up rich, but a life of privilege did not equal domestic warmth, at least not with his father, an austere, regimented, well-liked but disapproving man. Much of the book is set at the family estate in the Adirondack Mountains during Hochschild’s childhood. “Those summer evenings when I waved goodbye to him and was secretly relieved to see him go, until I held his hand as he died and then was apart from him at last.” The closeness never comes, although the son is dutiful. He becomes his own man, too—Hochschild was the co-founder of Mother Jones, and has made a career out of writing books about the injustice of colonial cultures, notably King Leopold’s Ghost. He has a novelist’s sense of detail and pacing, which are deployed with quiet force in this story of the interminable distance that exists between fathers and sons.

Patrimony: A True Story by Philip Roth

Roth’s family and his childhood in Newark, New Jersey, was the rich stew that the author mined time and again in his fiction. But this terse memoir about his father aging and dying, published when Roth was 57, is one of his most plainspoken and accessible books. His father, Herm, was not an easy man, but Roth details his last days—taking care of him, bringing him to doctor’s appointments, distracting him with conversation about the Mets—with clarity and without rancor. Roth never loses his sense of humor. When his dad has an accident in the bathroom, it is both hilariously grim and grimly hilarious. But Roth never strips his father of his dignity. It is tough going—the kind of book that is difficult to read when you are young—blunt, but not unkind. And although it is not a long book—the language is spare and compact—it is one you want to savor. Roth is not sentimental, but make no mistake, this tribute is nothing short of a love story.