With their rich but streamlined 2010 Whitney Biennial (cleverly titled 2010) curators Francesco Bonami and Gary Carrion-Murayari were looking to bring the museum back to its contemporary roots. The pulse-taking show, which begins today and runs through May 30, remains pleasantly true to the organizers’ stated mission: to take stock of the sort of ideas, working methods, and obsessions rumbling through America now.

“In the last 10 or 15 years, every bloody group show had this smart title—my own included,” Bonami says. “You start to build the show around the title in the sense that you force works that really don’t belong. We think the Biennial is a moment in time. And being a moment in time, the title is that moment in time.”.

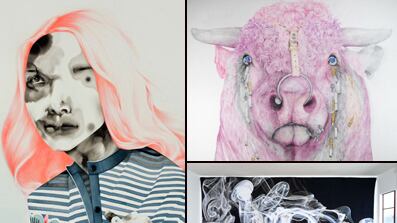

Click Image To View Our Gallery Of the 2010 Whitney Biennial

This Biennial is considerably smaller than the 2008 edition (55 artists versus the 81 who were featured two years ago), but it doesn’t feel that way. Much of the work is the kind you want to spend time with—art that’s worth absorbing, considering, and remembering. I started on the fourth floor where Piotr Uklanski’s gnarly hemp tapestry, Untitled (The Year We Made Contact), 2010, greeted me at the elevator bay. It set the tone, in a way—the earthiness of the medium, a certain handmade quality in the weaving and stitching, and a Lucio Fontana-esque gestural instinct to cut, slash, and deconstruct one’s own work.

Charles Ray has a suite of 15 ink-on-paper paintings in an adjacent room, depicting flowers with sinewy, rainbow-colored petals. It’s an interesting choice (as Ray is best-known for sculptures, such as the life-size toy firetruck he installed in front of the Whitney in 1993), and 15 might be 10 too many, but works like these place Bonami and Carrion-Murayari firmly on the anti-sheen, anti-fabrication route—something the art world has been craving now, post-bust, post-post-Hirst-a-palooza.

There are plenty of painters in this Biennial and many of them are grappling with a structured abstraction—paintings that come out of specific and more traditional modes of representation. Lesley Vance, for one, looked to Spanish still-life painting to achieve the unusual shapes, careful brushstrokes, and elegant handling of light and dark in her small abstract works. Tauba Auerbach’s obsessive, photorealist renderings of folded fabrics and unusual textures have a delightfully adverse effect, her level of detail and the larger-than-life scale making the works seem remarkably abstract.

The most arresting piece in the show comes from the Bruce High Quality Foundation, an anonymous collective of anti-market, anti-art school pranksters (their motto: “Professional Problems. Amateur Solutions”) who, of course, are all the talk of the art world that they so fiercely oppose. Titled We Like America and America Likes Us (2010), their contribution is a white Ghostbusters Ecto-1 (i.e. a vintage Cadillac Miller-Meteor hearse/ambulance)-cum-mobile museum. The room is dark, the headlights are on, a well-edited video plays on the windshield, and a measured female voice speaks about America like a long lost summer fling or, at times, a red-headed stepchild (“We like America and America likes us, but something keeps us from getting it together,” she says). The video is a mashup of YouTube clips, old-school Hollywood, and network news. It’s like the show itself, in that sense—a frenetic assessment of where we are now.

Pae White’s tapestry of smoke billowing on a black background opens the third-floor installation and it doesn’t have the same sort of energy as Uklanski’s work. But the floor itself is positively buzzing. Bonami and Carrion-Murayari wanted to do something different with the video artists included. Instead of dark, unwelcoming rooms scattered among paintings and sculptures, the curators built a labyrinthine network of galleries, each dedicated to a single work of art. "We divided the museum like layers of a cake,” Bonami notes, “at the end, you taste the whole thing, like a bite."

The first gallery is a collaborative piece by Edgar Cleijne and Ellen Gallagher (and the only immersive “environment” in the show). Inside Cleijne and Gallagher’s massive wooden container, JFK’s discombobulated head hovers over a spinning LP on a center screen; bright, abstract, stained-glass-like compositions flash on all four walls; the familiar hum of various projectors seem to heighten the experience; and the whole thing has a distinctive sort of “art studio” smell—fresh paint, fresh wood.

Videos by Kelly Nipper and Rashaad Newsome take us back to the ‘60s-era Judson Memorial Church days, with dance-as-performance-art (Nipper’s take being abstract and desexualized, Newsome’s being the opposite). And in her videotaped attempt to climb out of a narrow sheetrock column, Kate Gilmore recalls process-driven performance artists like Vito Acconci and the indomitable Marina Abramović. Kerry Tribe’s 16mm H.M. (2009) is the only real narrative-driven film of the bunch. It’s excellent and totally worth a complete viewing (have no fear: It’s only 18 minutes long). With a cast of incredibly naturalistic actors, Tribe retells the true story of H.M., a man who, in the 1950s, had part of his brain removed in an experimental procedure aimed at curing his epilepsy. H.M. consequentially lost the ability to form new memories (as in Memento) but his willingness to work with MIT scientists can be credited for much of what we know about the brain today. The whole thing is very elegantly done, with side-by-side projections playing off of each other and the occasional hand-drawn animation. It’s also a definite upgrade from the major narrative film included in the 2008 Biennial: Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke.

The one film that didn’t sit particularly well with me was Josephine Meckseper’s Mall of America (2009), in which the artist set shots of the commercial mega-mart to a dark instrumental soundtrack. She focuses on overweight shoppers, cheap items carried in bulk, and signs reading “Up to 50% Off.” We get it: Rampant consumerism is bad, Middle America is fat. The piece reads as heavy-handed, stale, and elitist. After all, this is a recession and what’s so bad about buying wool slippers on sale?

That brings us to the cool down—the quietly enriching second floor where excellent draftsmanship (Aurel Schmidt, Dawn Clements, and Storm Tharp) meets tactile sculpture (Huma Bhabha), and feminist diatribe (the hilarious video artist Marianne Vitale).

It’s an exciting show and far more user-friendly than the last edition. Bonami and Carrion-Murayari write that “time is what makes shows different from one another.” They acknowledge that some of their Biennial artists will fall by the art historical wayside (sadly, it’s not too hard to guess which ones) and they stand by their slice-of-life approach; this isn’t the 2010 art show, but rather a 2010 art show.

And now for the bad news: Bonami and Carrion-Murayari aren’t shy about making their politics known—a fact that clouds some of the excellent work they’ve done here. Barack Obama appears on the exhibition catalogue cover wearing a cowboy hat (upon first glance, and given the context, I thought it was Joseph Beuys). The curators’ unbridled love for the president doesn’t stop there: “With the election of Barack Obama, the clouds broke and the rain of renewal poured over the entire country,” they write in a joint catalogue essay, crediting this “reassuring and inspiring political figure” with giving artists the gall to address intimate concerns in their work again.

The love-fest continues as Bonami and Carrion-Murayari discuss the sort of cross-country canvassing they did to unearth the most timely and interesting art in America. “We looked to Hawaii, but without success,” they write. “We did not feel too bad though, since Hawaii is celebrated by having the coolest artist of all in the White House.”

In this case, I wish they had just let the work speak for itself. Nothing against Obama (or optimism, for that matter), but it’s just the sort of hero worship that both Fox News and Jon Stewart would have a field day with.

Plus: Check out Art Beast for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Rachel Wolff is a New York-based writer and editor who has covered art for New York, ARTnews, and Manhattan.