There is not a single frame of Black Is King that is wasted.

You could freeze the action at any moment and spend untold amounts of time lavishing in the striking visuals, appreciating the framing and studying the juxtapositions in color, fashion, nature, elegance, past, and present that are in beautiful, constant tension. Especially with the context of the music and lyrics enlivening every scene, each sequence invites exploration and consideration about Black history, African culture, and our current moment in time.

Black Is King is a triumph, elevating the standard for what a visual album is, could be, and, most importantly, could say—a standard that Beyoncé set herself with Lemonade in 2016.

A cinematic companion to The Lion King: The Gift, the soundtrack album tie-in to the Lion King remake that Beyoncé curated, the project features the star as its lead director, credited here as Beyoncé Knowles-Carter. Kwasi Fordjour, the Ghanaian creative director of her Parkwood Entertainment company, serves as co-director, and the pair enlist an army of African and American artists and talent, including Knowles-Carter’s own family, in what becomes a lush and emotional love letter to the African diaspora, to Black people and culture, to tradition, to identity, and to the future.

There’s a brilliance to the simple story: a young boy coming into his own and his power, following the framework of The Lion King. It’s a simplicity that’s downright renegade.

Black Is King recenters an African story that Disney told using animated animals and with a white creative team. That this project premiered on Disney+ could be construed as a Mouse House self-own, but that strips Beyoncé and the artists involved of their agency and mission.

They are reclaiming and correcting the Western and white narrative. The message in Black Is King is vibrantly clear: Blacks in Africa were and are thriving. It’s a depiction and reflection of Blackness that Hollywood ignores and sometimes actively hides, pointedly put on display here in a tie-in to The Lion King and Disney.

There is a timely resonance to all this that is evident from the opening moments. It’s in every visual, just as it was in the lyrics of The Gift, which were powerful in their own right when the soundtrack was released last year. But in light of these past months, the words sing like sirens, demanding to be heard. Every image is crafted so as to not just be appreciated but to compel you to the point that you can’t look away.

It’s the kind of project that changes how you see the world, which is to say that it finally reflects the world as it was and is—more, at a time when people might finally be ready to process what that really means.

In an Instagram post last month, Beyoncé celebrated the release of the film’s trailer, writing, “The events of 2020 have made the film’s vision and message even more relevant, as people across the world embark on a historic journey. We are all in search of safety and light. Many of us want change. I believe that when Black people tell our own stories, we can shift the axis of the world and tell our REAL history of generational wealth and richness of soul that are not told in our history books.”

There’s so much to unpack about Black Is King, it’s impossible to know where to start.

Do you begin with the fashion? It’s impeccable, curated by Beyoncé’s longtime stylist and costume designer Zerina Akers. The looks are a seamless blend of couture and traditional, mixing high-fashion, street style, tribal wear, camp, and everyday culture. Even calling out standout looks would take too much time; every outfit in “Water” alone—the pink dress!—is worthy of a dissertation.

How about the ways in which the words sear themselves onto this imagery, together flaming with resonance amidst the Black Lives Matter revolution of the last few months?

<p>“Let Black be synonymous with glory.”“Life is your birthright. They hid that in the fine print. Take the pen and rewrite it.”“No true king ever dies. Our ancestors hold us from within our own bodies, guiding us through our reflections.”“Our ancestors guide us through our own reflections—light refracted.”“To live without reflection for so long might make you wonder: do you truly exist?”“History is your future. One day you will meet yourself back where you started, but stronger.”</p>

Amidst an unignorable discussion about race at America’s present and what the future holds, every part of Black Is King inserts history into the discussion. The Lion King narrative on its surface encompasses that idea, but it plays out much starker here: the future of youth and what the community has already endured, and what parts of that burden will still be shouldered.

The film is dedicated to Beyoncé’s son, Sir Carter, in a note at the end of the film that also says, “And to all our sons and daughters, the sun and moon bow for you. You are the keys to the kingdom.” Her daughter, Blue Ivy, appears throughout the film, and her husband, Jay Z, and mother, Tina Knowles Lawson, show up as well. It drives home the point of how much of experience is generational.

Then there’s the filmmaking to discuss.

Beyoncé recent visual works showcase a compelling interest in tableaus and cinematic portraiture. The most interesting images happen with its subjects in stillness, telegraphing a certain kind of regality, a strength and serenity on their faces. She’s done it before, in Lemonade and in “Apeshit,” specifically, the latter putting her family’s visage in the Louvre alongside the Mona Lisa and making us interrogate what we consider worthy to be called art and masterpiece and why.

Any time a person appears on screen, she’s making sure they are truly seen before she moves onto the next image. New scenes are established with intense zoom-ins on the person in frame, lingering longer than we’re typically used to; a luxuriation built out of initial discomfort.

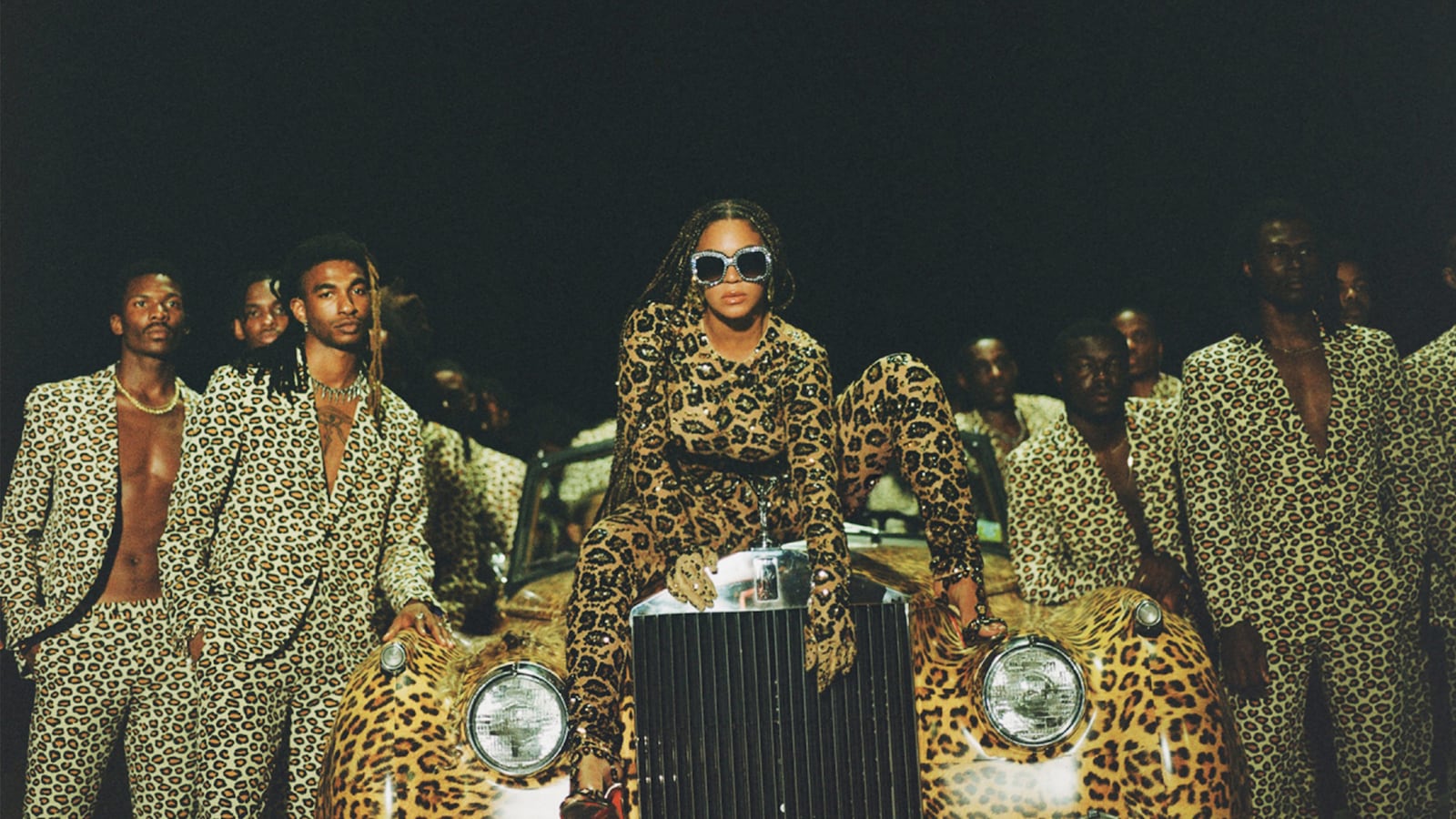

The life that breathes throughout the piece means space for humor and lightness, too. A leopard-print convertible drives us into the standout “Mood 4 Eva” sequence, replete with a ballet of synchronized swimmers in Technicolor bathing suits, a human chess game, and a particularly fabulous pair of narrow cat-eye sunglasses.

But even the cheekiness of the sequence pokes at something powerful. Throughout Black Is King, and especially in this segment, Beyoncé casts herself as a queen bordering on deity status, defying us to question whether such a pronouncement is hubris, earned, or both—in other words a Black woman asserting white male privilege.

Then there’s “Brown Skin Girls,” featuring appearances from Lupita Nyong’o, Naomi Campbell, Kelly Rowland, and such unapologetic joy your heart starts to beat a little faster when watching it. The a cappella start to “Spirit,” backed by a gospel choir, is about as moving a sequence I’ve seen this year.

It’s all so vital, so stunning, so thrilling, and so considered that the most glaring flaw—the music itself often doesn’t measure up to the level of art—almost goes unnoticed. Because of that, it could be questioned whether Black Is King does rival the best of Beyoncé’s work. It doesn’t have the element of surprise that accompanied everything else so pioneering about Lemonade. But there’s so much to admire and interpret, that any ranking exercise seems unjust.

This is also a piece of art that is about identity.

I’m a white male American, a white male entertainment critic, and white male Beyoncé superfan. Those identities inform how I see the world, how I see art, and how I see Beyoncé’s work. With Black Is King, I also think Beyoncé is drawing into focus not just how I see but what I see—what images, filtered through those identities, are actually put in front of me. Or are sought out and given validation.

This is a case where Beyoncé did not make this project “for you,” so to speak. Yet she is also demanding your attention.

It’s an entirely different prism and experience than that of a person whose identity is being acknowledged and celebrated in Black Is King; in essence, being crowned. Their readings of this film are more vital, and I can point you to some that I’ve loved.

At the end of her Instagram note, Beyoncé articulated her hope for what Black Is King would accomplish, goals that, through any lens, she undoubtedly accomplished: “I only hope that from watching, you leave feeling inspired to continue building a legacy that impacts the world in an immeasurable way. I pray that everyone sees the beauty and resilience of our people. This is a story of how the people left MOST BROKEN have EXTRAORDINARY gifts.”