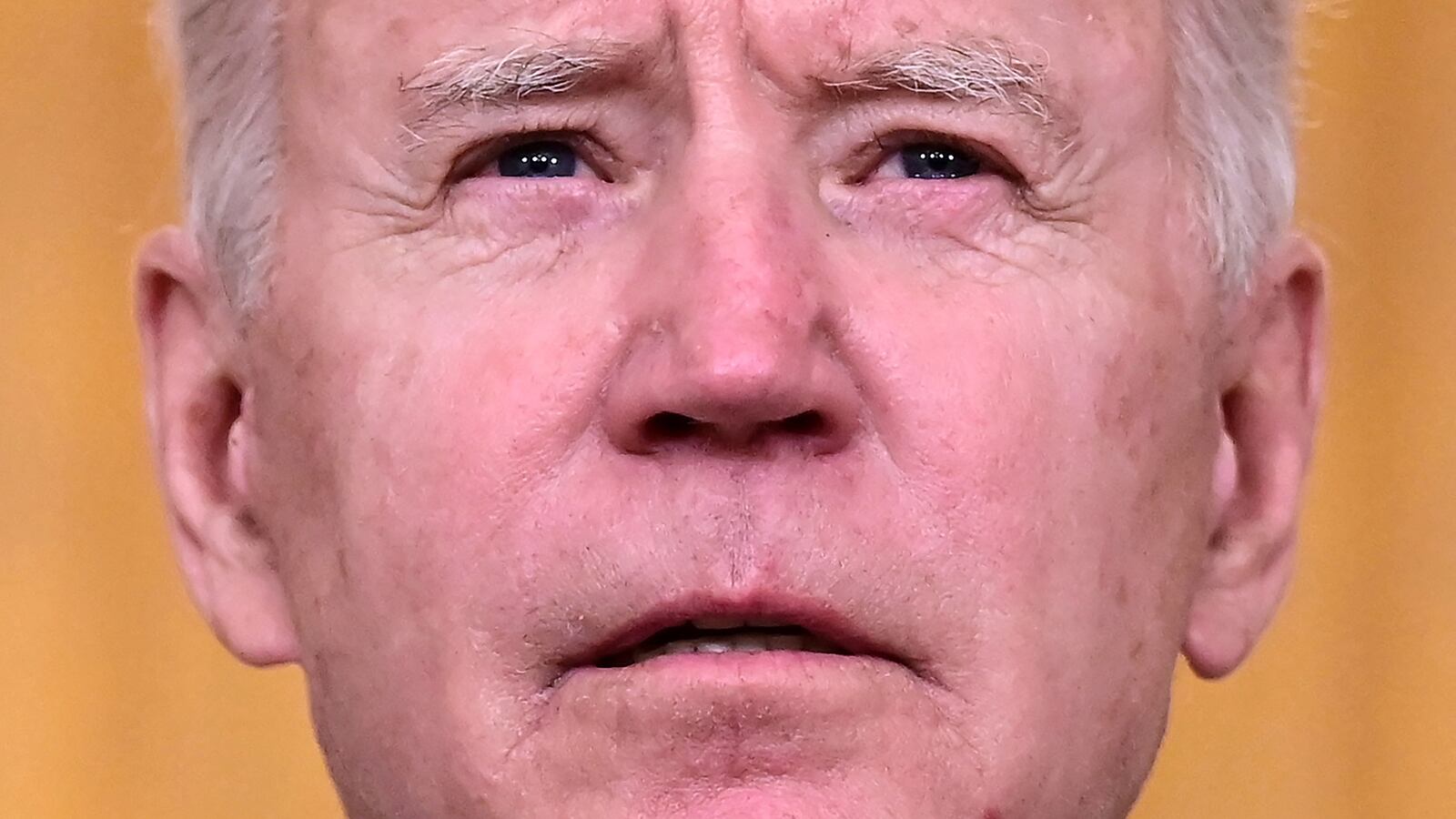

Ninety-eight days ago, President Joe Biden set a high bar for how he—and all of us—would be measured by future generations.

“We will be judged, you and I, for how we resolve the cascading crises of our era,” Biden predicted in his inaugural address as president to a beleaguered nation. “Will we rise to the occasion? Will we master this rare and difficult hour? Will we meet our obligations and pass along a new and better world for our children?”

“I believe we must,” Biden said, “and I believe we will.”

In the months before and in the months since, Biden distilled those “cascading crises” into a list of four looming catastrophes, each one of which was converging and reinforcing the other three, like tidal waves.

“The worst pandemic in over 100 years. The worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. The most compelling call for racial justice since the sixties. And the undeniable realities and accelerating threats of climate change,” Biden said in August, as the nation was gripped by the second of three waves of the coronavirus pandemic, record unemployment, nationwide unrest over police violence, and the most active hurricane season in history. “Four historic crises, all at the same time—a perfect storm.”

Now, hours before Biden’s first address to a joint session of Congress and days before his self-imposed deadline to bring the nation back to some version of normalcy, his administration has made strides in subduing the two most pressing crises—a task that once seemed impossible under his predecessor. But as the government response to the pandemic pushes the virus into a slow, uneven retreat, Biden now faces an even steeper climb, and concern from allies that not every crisis will inspire so unified a government response.

‘No Perfect Solution’

Of all the disasters inherited by the Biden administration, the coronavirus pandemic has been the one that weighs most heavily on the president. Every day, Biden receives a notecard bearing his name, a printout of his schedule, and the newest numbers for the national death toll from the virus. (The toll, as of Tuesday, had reached 569,771 people.)

Biden had nowhere to go but up. The Trump administration left the government response to the pandemic in tatters, with a list of don’t-haves that included insight into the nation’s vaccine supply and the intended allocation thereof, coherent guidelines for who was eligible for a vaccine first, or any guarantee that states, whose budgets were eviscerated by the recession, would even be able to support the vast expansion in testing and vaccination rollout they were tasked with implementing.

“What we’re inheriting from the Trump administration is so much worse than we could have imagined,” White House coronavirus response coordinator Jeff Zients said in a call with reporters on the first day of the new administration whose COVID-19 response he was tasked with leading. “We have to vaccinate as much of the U.S. population as possible to put this pandemic behind us, but we don’t have the infrastructure.”

Combined with a record-low—and occasionally well-deserved—mistrust in the federal government’s ability to respond to the greatest mass-casualty event in American history, Biden essentially had to start a mass vaccination campaign from scratch, according to public health experts involved in the effort.

“The interventions were all related to behavior, and we simply did not have the consistent communication that we have had in the past—giving a single message to get people to do the rational steps,” said Dr. Arnold Monto, a professor of epidemiology and global health at the University of Michigan and a former adviser to the World Health Organization. “Part of the message had to be, there is no perfect solution.”

The message to Americans—to embrace 100 more days of isolation, of masking, of sacrifice—in exchange for a commitment from the president to vaccinate 100 million (and later 200 million) Americans, has largely succeeded. Biden, of course was always going to be judged by a different metric than the man who largely stopped giving a shit about the pandemic after he personally avoided becoming “one of the die-ers.”

“The federal government took full responsibility for this vaccine program—we didn’t just say it was a state and local problem,” White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain, himself no stranger to managing a once-in-a-century public health crisis, said during a digital event at Georgetown University five days ahead of Biden’s joint address.

Some aspects of Biden’s response—appointing a national coordinator for government response to the pandemic, rejoining the World Health Organization, getting the vaccine on camera to prove its safety and efficacy—was Pandemic 101. But signing a 13-figure spending package to invest in a vaccination infrastructure, reopen schools, put $1,400 checks in American pockets and extend unemployment benefits was far from a given, and may be the high water mark of Biden’s ability to successfully navigate razor-thin majorities in both chambers of Congress.

Nowhere will that challenge be more visible in the coming weeks than the push for Biden’s “American Families Plan,” an economic package aimed at families and taxpayers that is intended to address the structural inequalities in the economy. The plan, expected to be the centerpiece of Biden’s address on Wednesday night, would provide universal preschool, two free years of community college, and make the child tax credit permanent, among a host of other Democratic priorities that will cost $1.8 trillion in spending and tax cuts over the next ten years.

The plan would pay for itself by restructuring the tax code “to make sure that wealthiest Americans pay the taxes that they owe,” an administration official told reporters ahead of the bill’s unveiling. The plan would, for example, tax capital gains for individuals making more than $1 million a year at the same rate as regular income, and would eliminate the so-called “carried interest loophole,” which allows private equity managers to report income as carried interest to take advantage of lower capital gains taxes.

The rationale, the administration official said, is to make the tax system “about rewarding work in our tax code and not just wealth, something that the President has spoken to, on the campaign and as President consistently.”

The remaining and hardest part of the pandemic response may be dealing with the backwash of Trump’s most dangerous utterances about the virus—that it was fake news, and the mistrust in vaccines he has long espoused.

“The biggest problem going forward on COVID is persuading people to continue to do the social distance measures we need them to do until we get more of the population vaccinated, until everyone has a chance to get that shot—two shots—and finishing that vaccine distribution,” Klain said in the Georgetown livestream. “We made a lot of progress on that, but there’s still a lot of work to do.”

Biden has met the second of the four crises—an economy ravaged by the pandemic and the measures implemented to halt its spread—with a similar response. A pair of trillion-dollar spending bills—one infrastructure-slash-tax-slash-broadband-slash-green jobs plan, the other an as-yet unintroduced expansion of investment in childcare and family assistance—have either been formally introduced to Congress or are pending the president’s address.

Both of the proposals are wildly popular by modern standards, another key ingredient in the successful passage of the American Rescue Plan that Biden hopes to repeat.

The ‘Existential’ Threats

But where Biden’s response to the coronavirus pandemic and the recession has been methodical and largely without major political hiccup, that leaves two crises that can’t fit on an index card.

The president has described systemic racial injustice and the threat of climate change as “existential” threats both to America’s role in the world and humanity’s continued survival—and unlike COVID-19 and its economic wreckage, long predate the missteps of the previous administration. On both issues, Biden has made large—but also largely symbolic—strides, from record minority representation within his cabinet to rejoining the global community in committing to cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

But promises to sign historic legislation to address the issue in the near future, like so many other promises from the Biden administration, remain at the mercy of the Senate filibuster and its defenders. One hundred days into the administration, allies fear that the same crises that survived the Obama administration will continue unabated under Biden.

The most diverse cabinet in history was meant to indicate the importance that Biden would place on getting everyone a seat at the table for major conversations, a promise he has largely held to. The Congressional Black Caucus and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus have been folded in to every major conversation about COVID relief and economic recovery packages, with a large focus on vaccine and health-care equity, although early focus on vaccine hesitancy by Black people was later found to be overblown.

But with the withdrawal of Biden’s proposal for a national police oversight board, the future of law enforcement reform now hinges in the ability by congressional Democrats to pass a single bill, the George Floyd Justice In Policing Act—a bill that, unlike Biden’s other “Hail Mary” legislative accomplishments in his first hundred days, can’t be passed by using the reconciliation process to avoid the filibuster. While Rep. Karen Bass (D-CA), chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, and Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC), one of only three Black Republicans in Congress, have begun “serious” conversations about a path forward for the bill, the issue of repealing qualified immunity for police has been described by law enforcement unions as a political non-starter.

Meanwhile, another story that clearly has a racialized element—immigration—has been one of Biden’s more conspicuous missteps. With a massive glut of children at the border, the refugee cap nightmare, and a much ballyhooed bill on immigration that despite a big introduction has gone approximately nowhere, the Biden administration has essentially kicked responsibility elsewhere—although Harris’ role as the border czar indicates that they view it importantly.

Republicans have vowed to make immigration a focal point of their march to retake the House of Representatives, particularly in districts where Trump outperformed among Latino voters in the 2020 presidential election.

Climate and race are also two areas where the thinness of the Senate majority have limited Biden’s ability to pass meaningful legislation in ways that he has not struggled on COVID or the economy. Climate has been similarly optimistic, but with little concrete action or plans to make that happen beyond folding some aspects into COVID relief and jobs plans. Biden has rejoined the Paris Agreement and last week hosted a digital climate summit with unlikely participants including China and Russia, but remains silent on the “New Green New Deal” introduced last week by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR), which is even less likely to pass through this Congress than the American Citizenship Act.

On both these crises, Republicans feel clearly more comfortable fighting Biden, even though it’s through non-troversies about bans on hamburger meat or “woke”/union-busting corporations like Amazon or the Mx. Potato Head plastic toy empire polluting America’s public discourse as their forebears once polluted America’s public waterways.

Part of that inaction, however, may be strategic. Biden promised to neutralize the partisan rhetoric and learn from Obama’s mistakes. In his inaugural address, he called on his country to “stop the shouting and lower the temperature,” even while proposing dramatic policies to redress long-standing ills. “Politics need not be a raging fire destroying everything in its path,” he said. “Every disagreement doesn’t have to be a cause for total war.”

By not matching the Republicans grievance for grievance, reacting to every slight with a torrent of tweets, Biden has largely avoided inflaming already fraught conversations about race or climate even further.

But that doesn’t mean that attacks on more substantive grounds aren’t being tested out. Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK) accused climate envoy and former Secretary of State John Kerry of “arrogantly killing American jobs” for the sake of reducing carbon emissions on Monday. It was part of an increasingly aggressive posture on climate from Republicans who are increasingly likely to admit that climate change is real, but who add that fighting it isn’t worth the costs to the U.S. energy sector.

Opposition within the president’s own party, though, may be the real risk factor for defeating the final three crises. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), a staunch defender of the filibuster, has promised to stand athwart the massive American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan in the hopes of breaking them down into digestible pieces—and has promised to be hard to convince to change course.

“I am not going to be part of blowing up this Senate of ours,” Manchin told CNN on Sunday. “Why can’t we try to make this work? If you have the violent swings every time you have a party change, then we will have no consistency whatsoever.”