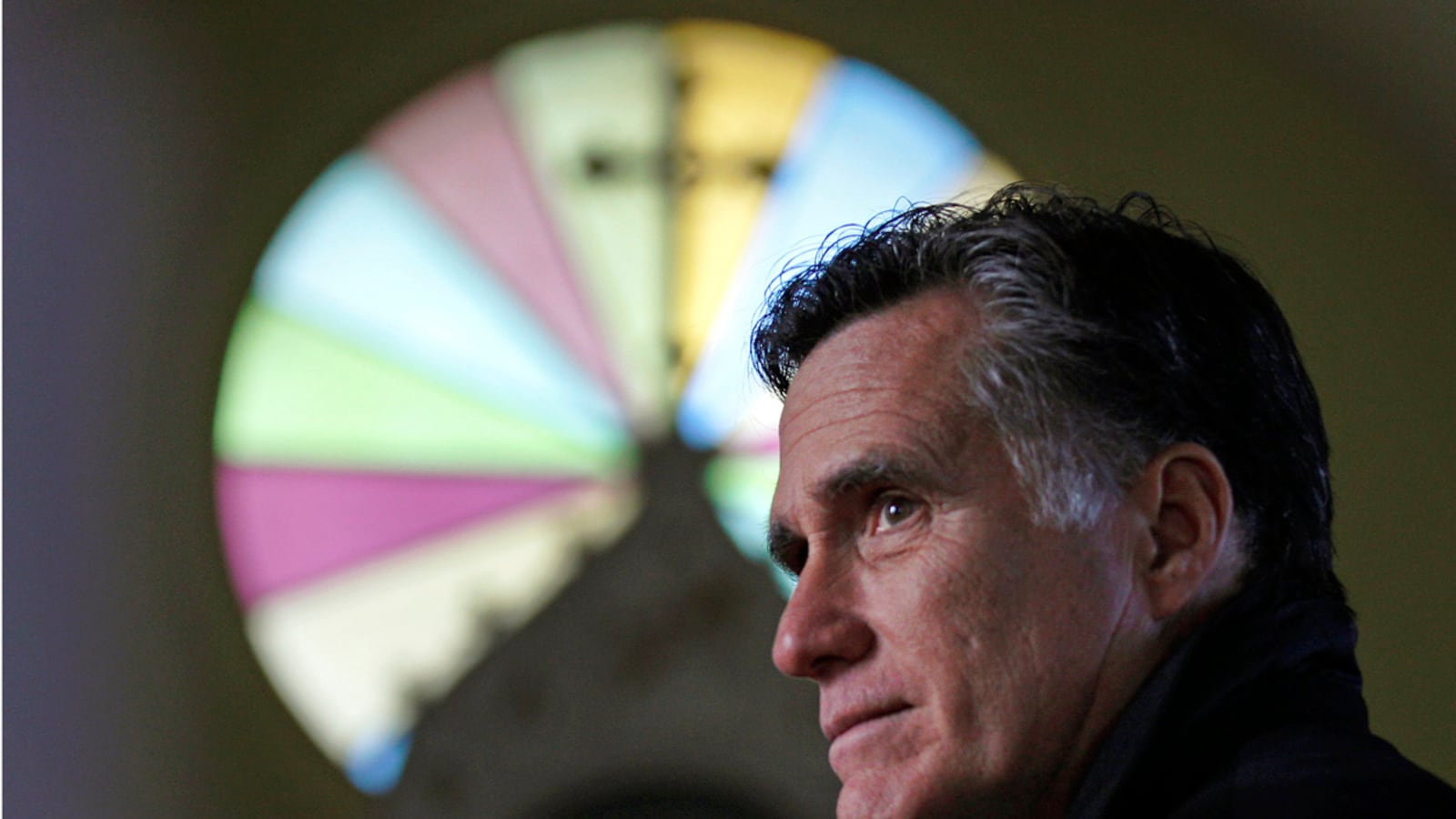

Same-sex marriage has taken center stage in the presidential campaign, and we know where President Obama stands. But while Mitt Romney has stated his opposition to it, less clear is the extent to which his own “evolution” on this and other thorny social issues are directly related to the Mormon church.

In Mitt Romney: An Inside Look at the Man and His Politics, the journalist R. B. Scott recounts the numerous trips Romney has taken to the mountaintop to square his positions on social issues like abortion and gay rights with church hierarchy.

Scott, a former staff writer and editor at Time, is Mormon himself and a distant cousin of Romney’s, and advised Romney early in his political career about how to deal with Mormonism in the public square. In his book he describes how Romney came away from these Salt Lake treks bolstered by a flexible understanding he reached with the brass: He was able to moderate his views during his runs for Senate and the governorship in liberal Massachusetts, yet he could still find his way back to doctrinal purity once in the governor’s mansion and safely on to his way to the White House.

After one such 1993 mission to the Church Administration Building, half a block from Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Romney returned to Boston and sought Scott’s advice in preparing for his Senate race against Ted Kennedy.

“I may not have burned bridges,” Romney told Scott, “but a few of them were singed and smoking.” Scott says that 1993 trip “established a pattern” that Romney “would follow in years to come when deliberating about whether to run for Massachusetts governor in 2002, and, especially, before announcing his candidacy for president in 2007.”

In the spring and early summer of 2005, while Romney was still Massachusetts governor and preparing to set up his first presidential PACs, he visited Salt Lake so often that one senior church official said he “basically camped out” at church headquarters, according to Scott. Gordon Hinckley, the president and prophet with decades of ties to the Romney family (he and Mitt’s father, George, went to high school together), reportedly found the frequency and “dithering,” as Scott put it, “a little tiresome.”

Romney “was left with the distinct impression that the Hinckley was not worried one whit about the additional scrutiny a presidential campaign might focus on the church and its teachings,” Scott writes.

A spokesperson for the Romney campaign declined to comment on Scott’s book.

While we cannot know exactly what Romney discussed with church elders in the meetings, the disquieting and under-reported side of this saga is that he made several more vetting trips to Salt Lake than John Kennedy ever made to Rome.

And these repeated visits raise questions about just how much the ever-flexible Romney has customized his social-policy views to satisfy—even temporarily—the Mormon church.

The other big difference between Kennedy and Romney is that when Romney made his first trip to Salt Lake, he was a stake president in Boston, meaning he oversaw 12 Mormon congregations and 4000 members across New England. In a lay church, Romney was roughly the equivalent of a bishop running as a candidate for senate. He “seemed oblivious to the fact that extra scrutiny might be warranted in his case,” Scott concludes, “given his long history as a regional ecclesiastical church leader,” which amounted to 14 years at that time.

“Surely no sitting stake president, particularly one with Romney’s sense of propriety,” Scott writes, would have “diverged from standard church policy” as Romney’s “nuanced views” favoring choice and “same-sex arrangements” did, “before sharing his views privately with the Quorum of Twelve Apostles and the First Presidency.”

In 1993, Romney went to Salt Lake with a Mormon pollster and poll results showing that he couldn’t win in Massachusetts without moderating his positions on those sorts of issues. “They realized it would serve no purpose to quibble—the greater good was to get him elected and give him a shot at realizing the victory his father booted 40 years earlier,” Scott writes. “Did they see him as a future presidential candidate? Did he? Do the statues of Angel Moroni atop every Mormon temple always face east?”

In other words, Scott is contending that the church in effect licensed Romney’s better-than-Kennedy promises on gay rights, as well as his pink flyers at the Gay Pride Parade in 2002 that beckoned: “All citizens deserve equal rights, regardless of their sexual preference.”

“Many Mormon moderates, even supporters of his approach to abortion and gay rights,” Scott writes, “figured Romney’s views put him crosswise with established church policies. Few seemed willing to acknowledge that his decision to preview his positions with senior church leaders in Salt Lake City had created additional elbow room for new faithful, if divergent, approaches to complex Gospel issues.”

But as soon as Romney took office, he reversed himself on abortion and gay rights, telling South Carolina Republicans in 2005, “Some [gays and lesbians] are actually having children born to them.” He derided Massachusetts as “San Francisco east,” and this year claimed he prevented it from becoming “the Las Vegas of gay marriages.”

He even eliminated the Governor’s Commission on Gay and Lesbian Youth, a panel that funded programs for gay teens and was founded by his Republican predecessor. Romney was proud of his gay-rights swing. “Now, someone will say look what you wrote in 1994 to the Log Cabin Club”—where he made his “better than Kennedy” boast—“well, okay, let’s look at that in the context of who it’s being written to.”

While the church may have given him a pass in 1994 and 2002, Romney is now back on the beam with a religion as hostile to homosexuality as any in America. The furthest he will go today is to say it is okay if states want to grant hospital-visitation rights to same-sex couples.

When the church took a formal position in 2008 supporting Proposition 8’s marriage ban in California (issuing a decree that “the formation of families is central to the Creator’s plan”), Romney covertly donated $10,000 to the cause, funneling it through a nonprofit PAC he controlled in Alabama that did not have to disclose such donations.

His daughter-in-law Jennifer Romney, who lives in Massachusetts with his son Tagg, gave another thousand. Fraser Bullock, who ran the Salt Lake Olympics with him (his “Sancho Panza”) and remains one of his top campaign fundraisers, gave $49,000, as did Robert Gay, one of his closest associates at Bain Capital.

Some of his big campaign donors, like L.E. Simmons and Frank Vandersloot (through his wife Belinda), also bankrolled Prop 8. “We don’t get involved to the degree we did on this,” the church spokesman told The New York Times, pointing out how unusual it was that the church issued a decree about a political issue. The son of a former Mormon president kicked a million dollars in to Prop 8, and the Times reported that 80 to 90 percent of the early volunteers knocking on doors on behalf of the measure were Mormon.

So what does Romney really believe? Both Scott’s biography and The Real Romney, by Boston Globe reporters Michael Kranish and Scott Gelman, report that Romney called homosexuality “perverse” in an appearance at a Cambridge Mormon ward in 1993. Romney has denied it, but Kranish and Gelman count four witnesses who said they heard it.

To that, the leaders back in Salt Lake might say, “Amen.”

Research assistance provided by Jillian Anthony, Irina Ivanova, Clarissa León, Nicole March, and Kyle Roerink.

CORRECTION: A previous version of the story stated that as a stake president, Romney was the "equivalent of a cardinal running as a candidate for senate." The article has been corrected to reflect the more accurate comparison to a bishop.