Everyone knows what a novella is, but try to define the genre. The easiest and most flat-footed definition would be the one I frequently use: a novella is a long short story that is not a novel. But this can hardly pass for a definition. The American Heritage Dictionary, my favorite dictionary, is scarcely any better, though it provides two outs and leaves it up to you to choose which of the two your prefer: “1. A short prose tale often characterized by moral teaching or satire.” Or “2. A short novel.” The Merriam-Webster Dictionary also gives you two choices—though they’re hardly more informative: “1. a story with a compact and pointed plot.” Or “2. a work of fiction intermediate in length and complexity between a short story and a novel.” In fact, if you didn’t already think you knew what a novella is, you’d never grasp it from these definitions. In the end, I sought out the opinion of the grand-daddy of all dictionaries, the authoritative Oxford English Dictionary. To my complete surprise, it fared no better—actually worse: “Originally: a short fictitious narrative. Now (usually): a short novel, a long short story.” Stumped, I finally sought out Wikipedia. “A novella is a written, fictional and prose narrative, usually longer than a novelette but shorter than a novel.” Clearly unsatisfied by this, I clicked under the hyperlinked “novelette” and this is what I got: “A novelette is a piece of short prose fiction. The distinction between a novelette and other literary forms is usually based upon word count, with a novelette being longer than a short story, but shorter than a novella.” This gets us absolutely nowhere, and we are back where we started.

Everyone is familiar with the list of famous novellas: Death in Venice by Thomas Mann, The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy, Mozart’s Journey to Prague by Eduard Mörike, The Royal Chess Game by Stefan Zweig, and, my favorite, though it is always sold as a short story, James Joyce’s “The Dead.”

I’ve always loved novellas, namely because they exhibit a degree of concentrated psychological acuity, which novels, because they need to provide so much material devoted to plot, simply end up diluting. A novella is focused on one issue—doggedly. Space is a premium, but not time. A novella can span years, months, or days—provided there is a revelation at the end, and provided the story—or is it an elegy—is about a tremulous, forbidden desire. Best of all, and unlike a short story, a novella does not need that idiotic move called a twist at the end. Revelation is one thing; twist quite another.

So here is my list.

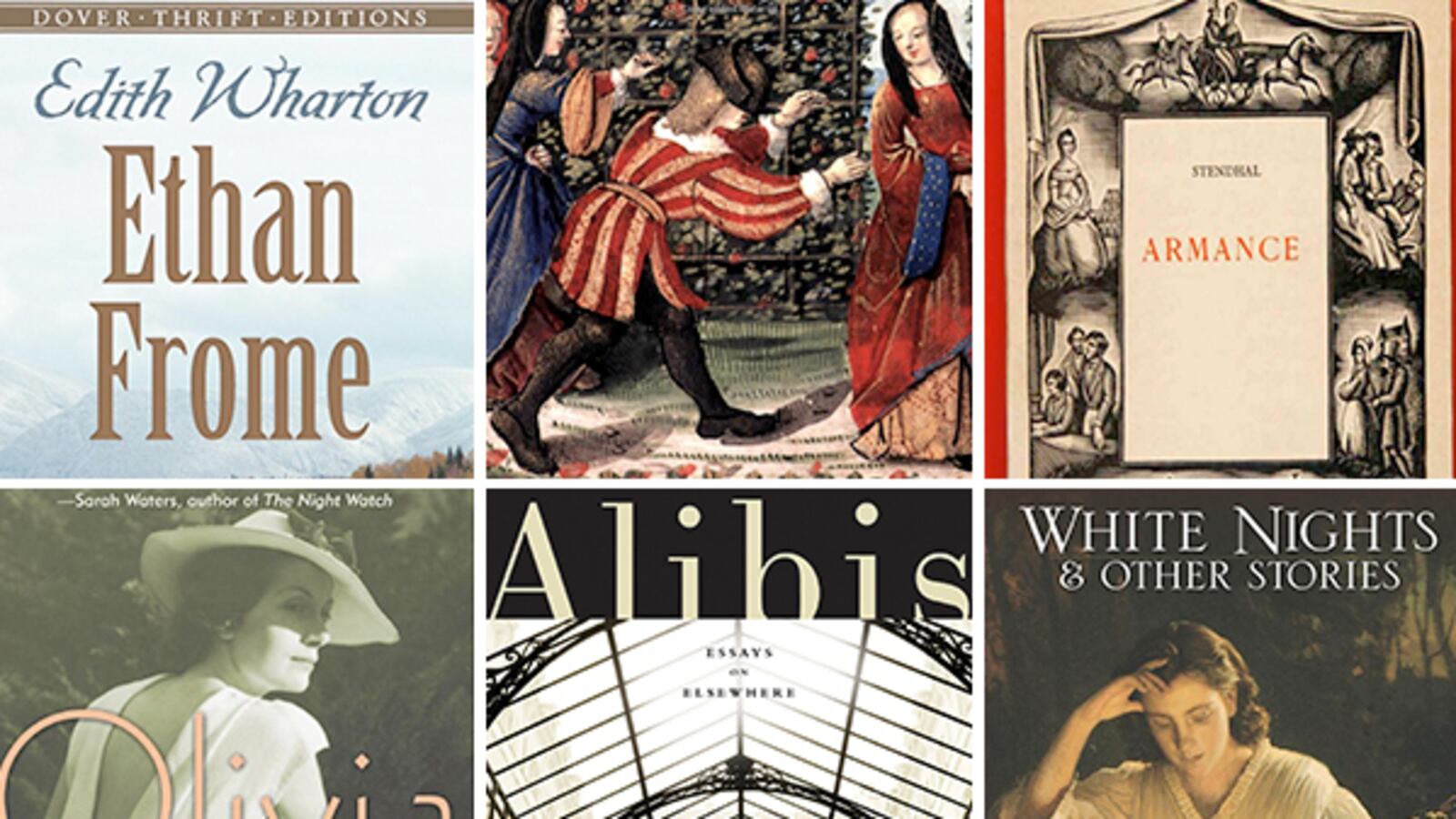

OliviaBy Dorothy Strachey

Dedicated to Virginia Woolf, Olivia by Olivia is the story of an English teenage girl in a boarding school in France and of her love for her school teacher, Mademoiselle Julie. The signals, countersignals, ambiguous inferences between two individuals scared of the love that dares not speak its name have never been so beautifully and elegiacally dissected. Olivia is the pen name of Dorothy Strachey, Lytton Strachey’s and James Strachey’s sister, who became André Gide’s English translator. Lytton wrote the classic Eminent Victorians and James, once Rupert Brooke’s lover, translated the complete works of Sigmund Freud. The Stracheys were part of the Bloomsbury Group, frequented by the Woolfs, T. S. Eliot and E. M. Forster. The book was translated by the famous French novelist Roger Martin du Gard and adapted for the screen by none other than Colette herself. It is a pity that this novel, after Penguin took it off the shelf, has never been published by a big enough house to keep it permanently on the shelves.

White Nights By Fyodor Dostoyevsky

White Nights is also an elegy to a love that never was. A young man called “the dreamer” walks along the canals of St. Petersburg on one of those nights in June when the sun never sets, and meets the proverbial damsel in distress. She is waiting to meet a young man who had promised a year earlier to return from Moscow on that very night to marry her. It seems he has failed to show up, and the girl is weeping. The dreamer tries to help, and fends off a man who is about to accost her with lecherous intentions. The dreamer has no friends, lives alone, and leads the most superfluous life so brilliantly portrayed by so many Russian novelists. But faced with this girl, his hopeless life prospects are suddenly illuminated. When he comes back the next white night, there she is again. She tells him of her life, he of his, and the two are practically determined to spend the rest of their lives together. But on the fourth white night, her beau returns from Moscow and whisks her away, leaving our dreamer to dream away the tremulous romance that never was.

ArmanceBy Stendhal

Armance was Stendhal’s first novel, published at the age of 44. It is the story of Octave, a young aristocrat who is disenchanted by life and whom nothing seems to move or captivate—until, that is, he meets his cousin Armance. The two are clearly attracted to one another. But for all their capacity to probe their own feelings, neither seems aware of what he or she feels for the other. Moreover, they are constantly misreading each other’s signals and, even when something seems to bring them together, some rumor or some mistaken guess will always draw them apart. Theirs is a courtship that cannot find the courage to speak their love, and though they will at the very, very end confide their love for one another and indeed get married, their love is never consummated. It has been speculated—with the encouragement of none other than Stendhal himself in a letter to Prosper Mérimée, the author of Carmen—that the reason why things never lift off (pardon the metaphor) between the two is because Octave is impotent. But this might be a red herring. I suspect that André Gide, who was a most canny reader of this novel, might have guessed that the real reason may have something to do with sexual inclinations that Stendhal was not comfortable describing.

Heptameron By Marguerite de Navarre

The 10th tale of the Heptameron is no longer than a short story, but falls in line with the original definition of the Italian novellas by Boccaccio and Bandello that inspired the collection of tales by the 16th-century author Marguerite de Navarre, sister to King Francis I. Marguerite de Navarre was a woman of unparalleled genius, and her ability to probe the human psyche until its most shameful, cunning motives are exposed was not to be equaled until another French woman a century later wrote what remains the first modern novel, The Princess of Clèves. In this 10th tale, Amador and Florida are not only of unequal social station, but she is naive and much younger than he is. But they are in love—or might be, we never really know—although their hesitant courtship is the stuff of legends. One thing or another is always keeping them apart, until it becomes clear that when all hurdles are removed the last thing that foils them is both her ambivalence and his own addled love turned into rapacious lust. Unable to fend off his desires, she finally takes a stone and damages her face in the hope of no longer attracting him.

Ethan Frome By Edith Wharton

Ethan Frome is the story of a docile husband who lives with his sickly wife and his wife’s impoverished niece, who has nowhere to turn except to work as a housemaid for her aunt. The wife is an embittered, odious, and vigilant presence in the house. But one evening, while the wife is away in another town for treatment, the two sit face to face and during a tremulous moment when both are about to avow their love, the cats break a pickle bowl to which the wife was attached. The wife suddenly returns and the couple is never even able to speak their love. They make a suicide pact, but this, too, like everything else in their brief love, fails.