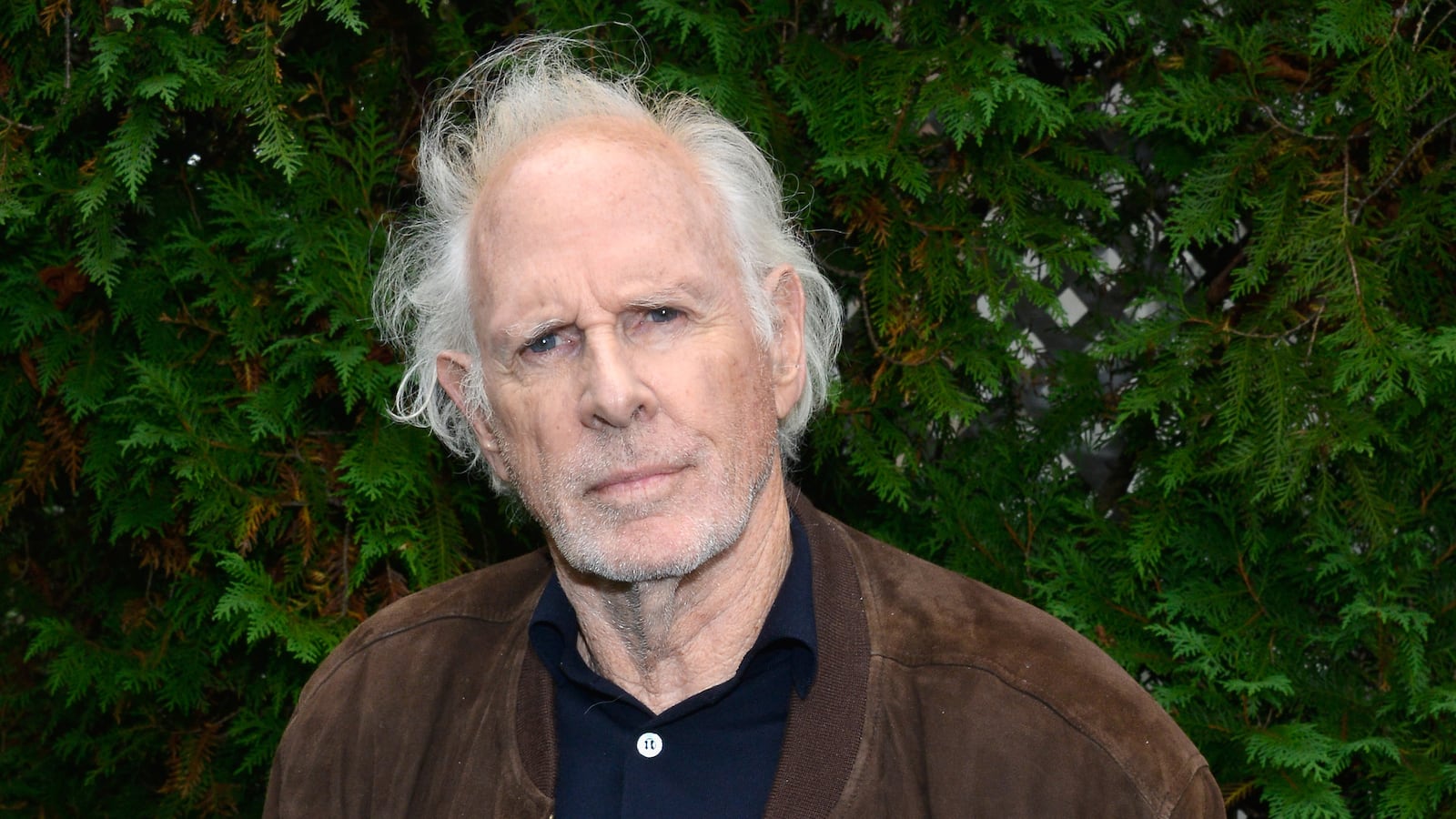

In the much-maligned 1974 film adaptation of The Great Gatsby, Robert Redford plays Jay Gatsby, a flashy pseudo-aristocrat who pines for the wife of Tom Buchanan, a philandering blue-blooded ingrate portrayed by Bruce Dern.

The harsh reality for Dern is, in Hollywood, their roles couldn’t have been more reversed.

For years, Dern looked on as his contemporaries like Redford, Duvall, and Nicholson—many of whom he called pals—transformed into bona fide movie stars.

“You put in your time, and then you get a break, but I never believed that,” says Dern. “And, as my age group ascended, Brucie was still on the bottom rung, saying five lines on an episode of Gunsmoke, and always playing bad guys.”

Forty years after the release of Gatsby, Redford and Dern are poised to go mano-a-mano once more, only this time the stakes are a wee bit higher. The pair of 77-year-olds (Dern has him by two months) are two of the front runners for the Best Actor Oscar, for Redford’s turn as a marooned seaman in All Is Lost, and Dern’s as Woody Grant, an ex-boozehound suffering from dementia who convinces his son (Will Forte) to accompany him on a road trip from Montana to Nebraska to try to cash in a junk lotto ticket in Alexander Payne’s Nebraska. Both are largely silent, beautifully modulated performances showcasing two different sides of courage from two disparate actors.

Dern’s is certainly the more surprising of the two, since, for starters, he’s never been given a role so perfectly tailored to him in his career. The crisp, black and white lensing, courtesy of Phedon Papamichael, emphasizes each and every crack and contour on his grizzled face, like a Grant Wood painting. It’s a character that demands Dern to constantly shift back-and-forth up to a dozen times in a given scene from zoned out to readily engaged, and by the end of his futile journey, he emerges as a Midwestern Don Quixote, a near-mythical paragon of dogged persistence in the face of adversity. Woody is the cinematic embodiment of Bruce Dern, and vice versa.

When Payne, Dern, and co. unveiled the movie at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, it was Dern’s third time premiering a movie at the ritzy Côte d'Azur fete. The first was in 1976 with Alfred Hitchcock’s Family Plot, which he describes as a “good experience,” because the screening coincided with Hitch’s 75th birthday. The second one, 1978’s Coming Home, didn’t go so well. Despite eventually receiving heaps of accolades, including Oscars for leads Jon Voight and Jane Fonda, and Dern’s only Oscar nod for his fiery turn as Fonda’s cuckolded husband, the film wasn’t received well because of “the subject matter, and they also wanted to pick on Jane,” says Dern. With Nebraska, however, the movie received a 10-minute standing ovation by the famously ornery French crowd. “I was shocked,” says Dern. “They seemed to clap for me when my picture came up during the credits, and Alexander turned to me and said, ‘Make no mistake about it, that’s for you.’ I just never had people clap for me in any kind of situation.”

The praise was so effusive that the Cannes jury awarded Dern the Best Actor prize.

“Bruce just popped into my brain when I read Bob Nelson’s script for the first time nine years ago,” says Payne. “When it came time for me to make it two years ago, I met a bunch of other people his age”—including Gene Hackman—“and circled right back around to him. In real life he’s so garrulous, and in this movie, he’s so laconic. And who else could have hair like that, walk like that, and be realistic as a Midwestern dude?”

Dern is indeed garrulous, and one helluva storyteller. He loved working with Payne, whom he calls the Vince Lombardi of directors—an expert, he says, at delegating authority. In an interesting twist, his daughter from his first marriage, Laura Dern, starred in Payne’s debut feature Citizen Ruth. In another interesting twist, while filming Hitchcock’s Family Plot, Dern says a then-7-year-old Laura would often visit the set and sit on Hitch’s lap. The set’s other frequent visitor was a young filmmaker by the name of Steven Spielberg, whose Amblin Entertainment offices were a stone’s throw from the soundstage.

“Hitch would say, ‘Bruce, what does that boy back there want?’ And I’d say, ‘Hitch, he just wants three or four minutes to tell you how much you’ve meant to his career,’” says Dern. “And Hitch goes, ‘I-I-Is that the boy that made the fishhh movie?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, that’s him.’ And he said, ‘Ah, I could never speak to him. He makes me feel like such a whore. Bruce, two years ago, Lew [Wasserman] asked me if I wanted to make $2 million in 20 minutes, and I told him, ‘I’m not a fool, of course!’ So I can’t look at him, or shake his hand, because I’m the voice of the Jawsss ride.’ He was freaked out by it because he took the money and felt it wasn’t right! And they never talked.” (Laura Dern would, however, go on to star in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park.)

He may not look it, but Dern does descend from nobility. His grandfather was George Henry Dern, former governor of Utah and secretary of war under FDR, while his father’s law partner was two-time presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson. Another family friend was FDR’s wife, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

“When I was about 4, we went back east for the summer, and they were at Hyde Park,” says Dern. “I rode a little bicycle, smacked into a tree, and had a concussion. In those days, when you had a concussion they’d strap your head to a pillow with a big belt. When I woke up, it was 11:30 at night, and I saw an old lady in a rocking chair. My eyes were woozy as I woke up, and I saw these spindly, veiny legs in slippers and a nightgown. I thought it was my grandma, but when I saw her face, I realized it was Eleanor Roosevelt.”

But the story that’s stuck with him the most happened early on in his acting career when, at the age of 21, he enrolled at Elia Kazan’s Actors Studio in New York. There were five up-and-coming actors under Gadge’s (their nickname for Kazan) tutelage—Dern, Rip Torn, Pat Hingle, Geraldine Page, and Lee Remick—and Dern was the baby of the group. After starring in the Kazan plays Sweet Bird of Youth and Shadow of a Gunman, and making his screen acting debut in an uncredited role in Kazan’s 1960 film Wild River, Dern felt it was his time to shine. He caught wind that Kazan was working on a film about college kids called Splendor in the Grass, and wanted in.

“Gadge said, ‘There’s no part for Brucie,’ so I said, ‘Why not? Fuck, I can go back to college. I just quit two years ago!’” exclaims Dern. “And he said, ‘It’s not right for you. Your acting is not the kind of acting I need in that movie. I need stars. Young stars.’ I said, ‘You really think Warren Beatty is that good of an actor?’ And he said, ‘I do. He’s a young star, and you’re not. No one will know who you are for a long time. You become the characters you play. You’re not a conventional leading man.’ So I said, ‘Then why did you bring me here? Why did you make me come to New York? I’m driving a fucking cab! I’ve got a baby, and I’ve got a wife!’”

Kazan paused, and said, ‘I’m not ignorant to where you are, or who you are. I’m the one that put you here, and I’m going to get you there. But it’s going to be an endurance contest.’”