Every January 25, Scots around the world gather to celebrate Burns Night, which pays homage to the birth of the country’s national bard, Robert “Rabbie” Burns. It’s a welcome joyous respite from the country’s long, cold and dark winter, when the glorious Scottish summers are a distant memory.

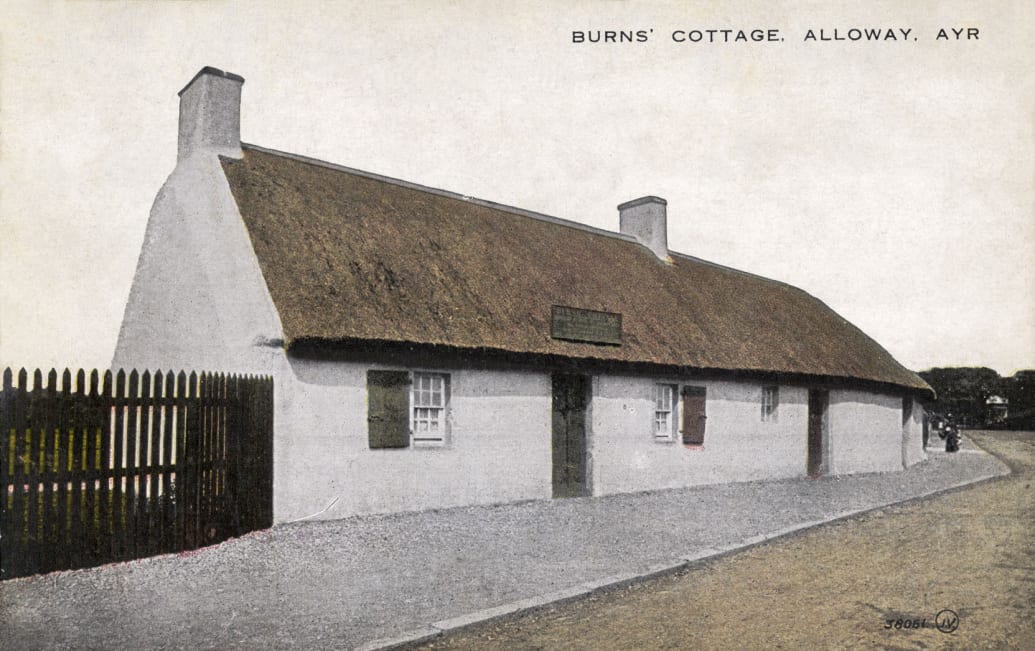

Perhaps most widely known for works like Auld Lang Syne that have been adapted numerous times over the years, Burns had a prolific career as a poet and lyricist. Born in the town of Alloway, Scotland, in 1759, he died at the age of 37. Five years later, his friends and family decided to commemorate the poet by hosting a party that would become a beloved tradition across the country.

Universal History Archive/Getty

He was lauded then and still today by artists, including singer Bob Dylan, for his political and social commentary. All these years later—2021 marks the Bard’s 262 birthday—Burns Night is a quintessential Scottish holiday featuring bagpipes, tartan, whisky fueled toasts, folk dancing and, of course, plates of haggis. Burns called the hearty delicacy the “Great chieftain o the puddin’-race,” in his famous Address to a Haggis that plays a central and essential part of the celebration.

And these days, the holiday has seemingly only grown in importance and is key to modern Scottish national identity.

“What I’ve noticed is that in Scotland, it’s become more popular among younger people [in their late 20s and early 30s],” says Andrew Weir, a self-described Burnsian and brand leader for Aberlour Single Malt Scotch Whisky.

Weir is originally from Ayr, just a two-and-a-half mile walk from Burns’ Alloway home. He links the increased prominence of Burns Night to the growing thirst for Scotch around the world. “When I was growing up, whisky was always what your older family members drank. But as people travel more, you realize that wherever you go, our culture has seeped into these far off places—and we should be really proud of it.”

Culture Club/Getty

While festivities may vary slightly from town to town and family to family, Weir says that the “traditional Burns supper does have a very well-known and well-accepted format.”

The night typically begins with a recitation of Burns classics Selkirk Grace and the obligatory Address to a Haggis. A savory, offal-based dish, haggis is traditionally encased and boiled in a bag made from the lining of an animal’s stomach. “A lot of people are always very, very curious as to what is in a haggis,” says Weir. “And I always joke, you know, what’s in the New York hot dog?” (Touché.)

But the unveiling of the haggis is no laughing matter. It enters accompanied by a kilt-clad piper and is ceremoniously cut before attendees who feast on the dish and a host of other traditional foods. You’re likely to find hearty Scotch soup as well as the classic side neeps and tatties (mashed turnips and potatoes). And be sure to save room for dessert, which is often a sweet and spiced clootie pudding made with dried fruit and treacle, a trifle or cranachan (made from cream, fresh fruit, Scottish oats and whisky). This is all, of course, accompanied by plenty of Scotch and more readings of Burns’ poems.

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty

Beyond the time-honored culinary elements of Burns Night festivities, it’s an inherently social event. But that aspect of the celebration is out of reach for many revelers this year. However, in spite of the strict lockdowns in place across the country, Scots have every intention of celebrating, replacing raucous dinners with Zoom toasts and haggis-to-go.

So if you’re looking for an excuse to extend the holiday cheer just a bit longer this year, here’s a look at how Scots are going to celebrate Burns Night and what they’ll be doing to pay tribute to the Bard during lockdown.

Burns’ work resonated with Weir from a very early age. By the time he was six, he was reciting his poems in the Lallan tongue (a dialect that Burns often wrote in) to rooms full of people with ease.

“My grandmother spoke in the language of Burns, so the language is familiar to me—it wasn’t foreign,” says Weir. “My joke is always that when I grew up, everything from a bath salt to a chip shop was named after Robert Burns. It’s just part of our culture, it’s everywhere.”

Though he says he wasn’t a “particularly studious child,” his knack for reciting Burns’ poems and lyrics gave him focus and confidence. Upon winning his school’s Burns supper competition, his connection to Burns only strengthened.

“I would be rolled out as this almost kind of curiosity, this little boy who just seemed to be very good at this,” says Weir. “There were times in my life, when I would show up at about 20 or 25 of these things in the month of January. I was maybe the youngest person in the room by 20 years. I just seemed to have a grasp of the language.”

In 1997, when he was 16, Weir won the Scottish championship for recitation—“which is entered by 182,000 people”—with his rendition of Holy Willie’s Prayer. (It’s Burns’ commentary on religious hypocrisy.) For nearly a decade, Weir channeled his love of Burns into his acting career and continued to appear frequently at Burns Night celebrations in costume as Robert Burns (including gigs at royal palaces and Disney’s Epcot Center).

“It’s been a real golden thread throughout my life,” he says. “I love his work and I defend him a lot, because he’s a complicated character. But I think his work has just been so impactful and powerful and has really taken Scottish culture global.”

His favorite poems include the romantic A Red, Red Rose and A Man’s a Man for A’ That, which is a song written by Burns in 1795 outlining his dream of an egalitarian society. These days, while Weir is still intent on sharing his love of Burns, he goes about it a bit differently.

“When I was growing up, it could be a very backward event—all men,” he says. “I started in my late teens refusing to show up at all-male Burns suppers. My thing is trying to present his work in a way that will interest people who would never in a million years think they would ever get anything from listening to 18th century Scottish poetry. I’ve done it in schools, in old folks homes, in drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs—whenever you can find something in his work that resonates with people.”

Aberlour Scotch Whisky

Weir has been working in the whisky industry for the past 12 years, during which time he’s also sought to dismiss the idea that Scotch and Burns’ poems are the domain of old men. He hosted a Burns brunch in New York last year and this year is putting on a virtual Burns Night with Aberlour for about 300 people. The event will feature musicians performing modern interpretations of Burns’ songs and recitations and poems by Scottish actors.

He had a haggis delivered to his home in Mount Kisco, New York, to enjoy during the virtual celebration with his wife and sons (who, at one and four years old, have not fostered a deep appreciation for Burns just yet). His guests will receive Scotch and haggis-flavored potato chips to enjoy during the event. He is particularly looking forward to hearing another of his favorites: Auld Lang Syne.

“It’s this incredible story of friendship and togetherness,” says Weir. “It’s so important right now, this idea of us being together. In some ways, the current environment and people’s appetite and attitude towards virtual events has allowed us, actually, to take the event to a new level and to involve people who may not have previously been able to be involved. I think it might be one of the Burns suppers I’ve been most excited about in my life. Burns’ work seems to make sense, almost all the time.”

Sue Lawrence, a prolific Scottish author whose writings include 19 cookbooks like Scottish Baking and A Taste of Scotland’s Islands, would typically be headed to a ceilidh (pronounced KAY-lee) for Burns Night.

A ceilidh “is a traditional Scottish gathering with traditional music—fiddle and accordion—and traditional Scottish country dancing,” says Lawrence, whose latest book, The Unreliable Death of Lady Grange came out last March. The event would generally include popular folk dances Strip the Willow, the Gay Gordons and the Eightsome Reel. “The men would often dress in kilts and the women perhaps wear a tartan sash or ribbon,” she says.

While she recalls learning and reciting Burns’ poems and songs throughout her childhood in Edinburgh, she didn’t start attending ceilidhs until later on in secondary school. “And then at university [in Dundee] there were always Burns suppers with haggis, riotous Scottish country dancing and far too many drams of whisky for some,” she says.

Country dancing is a given at parties and gatherings across the country.“Where there is traditional music, we will dance,” Lawrence says. “It is extremely energetic and often you end the evening with sore arms from all the ‘burling’—turning a partner around with wrists/arms.”

While she won’t be cutting up the dance floor tonight, she and her husband will be enjoying an array of Scottish culinary delights at home. There will be haggis, of course, but with a twist. (It turns out, it’s as versatile as Thanksgiving turkey.)

“We will be having a delivery from a wonderful French/Scottish restaurant on Burns Night of haggis bonbons served with mustard mayonnaise and a pickled turnip and red onion salad,” she says. “I love any dishes involving haggis and now often serve it in a haggis lasagna, a haggis grilled cheese toastie, haggis b’stilla or little haggis tartlets served warm with red onion marmalade.”

Also on the menu tonight: Scotch beef and root vegetable stew, local cheeses with oatcakes, Cranachan cheesecake and homemade shortbread (Scotland’s national cookie). Perhaps, she’ll end the night with one of her favorite Burns works Ae Fond Kiss, “whose words about love and parting and unrequited love are so very poignant.”

As a child, Iain McPherson celebrated Burns Night all over the world with his parents. The award-winning bartender and co-owner of Edinburgh bars Panda & Sons, Hoot The Redeemer, and Nauticus was born in Australia and moved frequently, living for periods in Thailand, Vietnam, Hong Kong and elsewhere, before moving to Scotland as a teenager.

“There’s always a strong Scottish community, wherever we’ve been,” says McPherson, whose father is Scottish and whose mother is South Korean. “We’d always find a community to celebrate Burns Night with no matter where I was living. Growing up was really cool, just experiencing new cultures, but also being able to celebrate Scottish traditions at the same time.”

Laura Meek

He’s always been partial to the Burns poem Selkirk Grace.“I like it because it’s very short—my patience isn’t the longest.” He also likes A Red, Red Rose,“from what I’ve gathered, Burns is quite a dreamer and quite a romantic.” And then there is the classic Tam O’ Shanter.

“It’s basically about the drinking classes of the time he was growing up in and it’s a really interesting and quite a funny poem,” he says. “It talks about a few characters that he obviously knows and it’s hilarious.”

One of McPherson’s favorite parts of the Burns Night celebration is being able to introduce newcomers to the uniquely Scottish food and drink served at the event.

“It’s very much a welcoming for people that aren’t from Scotland and make them feel part of the community,” he says. “It’s a good time for us to open their eyes to the variety of Scotch whiskies available. I always find that everyone has their mission by the end of Burns Night to win over people that are maybe a bit scared of Scotch.”

This year, with Scotland in a strict lockdown, McPherson and his business partner Kyle Jamieson are determined to at least keep the haggis-and-cheese toasties and Scotch flowing at Nauticus with take-out service.

Nauticus will also be releasing its own single cask whisky—a Glenglassaugh aged in Sauternes wine casks—for the festivities. “It’s a very easy drinking Scotch,” he says. “And, of course, goes amazingly with haggis.”