It is just after 7:30 in the morning at the CBS Broadcast Center, a gigantic former dairy distribution depot on the west side of Manhattan. Bill O’Reilly, the firebrand Fox News host, had just breezed through the lobby after a seven-minute interview on CBS This Morning, in which he, sounding very un-O’Reilly-like, announced his (qualified) support for gay marriage and immigration reform, suggested that he may have to move to Switzerland, and described himself as the only person at his network who acts as a legitimate journalistic watchdog.

Meanwhile, in the darkened shadows of the control room, Chris Licht, a 41-year-old blond bulldog and executive producer of the show, is screaming for Boston’s “More Than a Feeling” to introduce the next segment. Dozens of screens show what is happening on the morning shows on the rest of the networks and on cable. The mix of cooking segments, pop concerts, and celebrity interviews is met with an unappreciative murmur. “Oh, look, a red brick background,” Licht says, gesturing to CNN, a reference to how the cable network’s new morning-show set bears a resemblance to the one Licht is orchestrating from the control room.

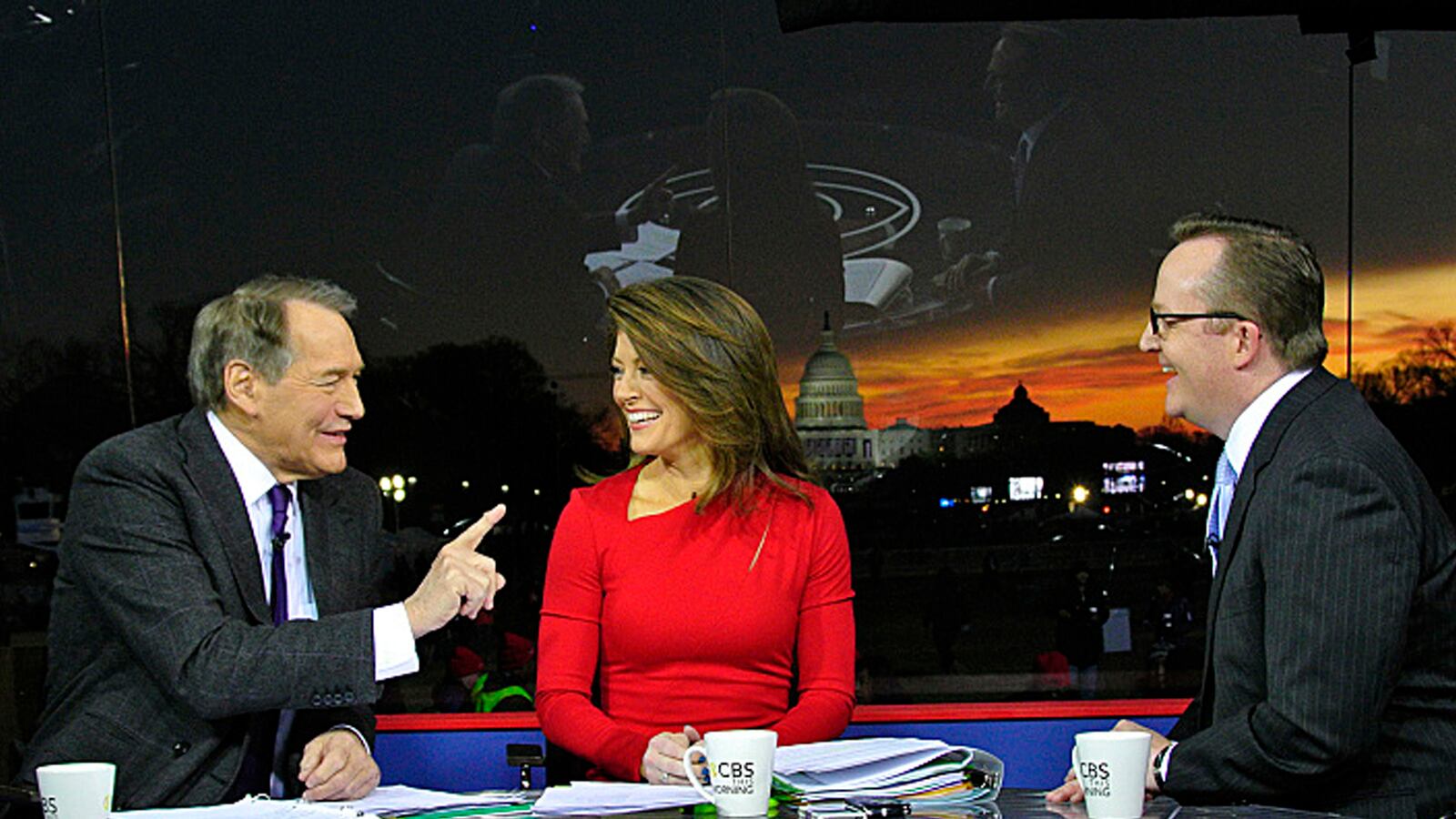

On the set, hosts Charlie Rose, Gayle King, and Norah O’Donnell are interviewing Michio Kaku, a theoretical physicist who explains why so much of the country is baking under the summer heat. Kaku has long, white hair and is an impish presence on the air, and the trio tries to keep the segment light in the morning-show style. The planet is warming, Kaku says, which means more air-conditioning units will be sold, more electricity will be consumed, “And,” he adds nonchalantly, “more people are going to die.”

The light banter stops. Rose’s mouth drops open. “AND GOOOOOOODDDD MORNING!!!!” shouts Licht.

CBS has lagged in the morning ratings race since roughly the beginning of morning television. At the end of 2011, especially dismal ratings led the network to scrap The Early Show altogether. It hired Licht, who had helped create Morning Joe on MSNBC, which despite ratings that are small compared with the networks had become must-see TV for political tastemakers.

The task Licht was given, he said, was simply to “blow up the morning. Not to tinker around the edges but to do something completely different.”

“There is a morning-show formula that is very successful. It is basically the format of the Today show,” he added, referring to the NBC program that had dominated the morning until some recent slippage. “The game plan everywhere was ‘Why not copy something that is successful? But just as people tried to copy Morning Joe and failed miserably, I think when you are basing your product 100 percent on trying to be somebody else, you fail miserably. Why would anyone see a copy when they can see the original?”

The vision, as Licht tells it, was to dispense with a lot of the dross that had made morning shows morning shows—the live pop concerts, the centenarian birthdays, even the weather man, and focus on what makes people turn on the TV in the first place. Instead, CBS This Morning would find out what is going on in the world.

They made the set similar to Morning Joe, with one large table instead of a series of smaller studios. They rely heavily on the CBS correspondents out in the field. Interviews in the studio are not one-on-one affairs typically but with all three co-anchors together.

Licht brought on King, a sunny, more traditional morning-news presence who co-hosted a show on Oprah Winfrey’s OWN and is close friends with the media mogul. O’Donnell came on the show after a stint as CBS’s chief White House correspondent. And Rose, of course, has hosted his high-minded eponymous PBS show for two decades. That program, with its black-box background and back-and-forth with leading newsmakers, is about as far from a morning show as can be imagined.

Rose, who is—or was, at least—a regular presence in the New York media cocktail-party circuit, said that to a person, everyone he spoke with about taking the morning-show gig warned him against it.

“I was in a certain place in my life, etc, etc, etc.,” he said. “And people said, ‘Don’t do this, you have nothing to prove, you have a great career, a great life, whatever whatever whatever.’ And because they were looking at what CBS had done in the past, they said this is not for you.”

So far, he says, no regrets, and none either for Licht and his grand experiment. Ratings released last week showed CBS This Morning with double-digit yearly gains in the 25-54 demographic and a 20 percent bump in overall viewership, closing the gap with the Today show.

Plus, it has been one of the few places on the networks where newsmakers go to make news. It is where Colin Powell announced his endorsement of Barack Obama, where Mitt and Ann Romney had their first joint interview of the 2012 campaign, and where Eliot Spitzer kicked off his 2013 comeback tour.

And with success comes a certain swagger. Not of a top dog, as This Morning remains comfortably in third, but one that says to those other guys, “We are coming for you.” It is impossible to talk to the crew at This Morning without what is happening on those other screens creeping into the conversation, even if they are an absent presence.

“I don’t think any show on the air beats our first 20 minutes at 7 o’clock,” said King after the end of a show last week. “When you look up and see what the other guys are doing, and I look every day at 7:30, quite often they are doing the same thing and we are doing something different. The first 20 minutes, I don’t think anybody can touch us, and it just goes up from there.”

King and her co-workers now expect to see others copy their formula, if they have not already, “I hear that from the other competitors, who say, ‘We are watching what you are doing over there. You are doing what we no longer do,’” King said.

Added Rose: “That is why we say, reimagine the morning. We don’t ask, this is what the Today show does, this is what Good Morning America does, this is what whoever does, and so therefore we have got to do that because this is what morning shows do.”

And Licht: “When we built the show, we sat in a room and said, ‘There has never been a morning show before. And we are not going to do something because the other guys do it and we are not going to not do something because the other guys do it. We are going to do what we think should be done in the morning. And that perpetuates itself every day. What are you going to lead with, what stories are you going to cover. There has traditionally been a culture of trying to be competitive in the sense of being the same, and we are trying to be competitive in the sense of being unique and original and on brand at CBS, and that is it.”

If others stick to their formulas, he said, it is because they are taking the easy way out.

“If you look at what the others guys do at the 8 o’clock hour, it is light and fluffy because that is easier,” he said. “It is easy to say three weeks out that you are going to do a demonstration about how hot it is and latest fall fashions on October 14. We agonize and sit and go over every minute of this broadcast to make it relevant.”

That’s not to say it can’t be fun. A couple of hours after Rose was contemplating the extinction of human life on the planet, the cameras were off and he was talking with O’Donnell and King about the interview with Kaku and trying to describe how he felt about it.

“A man crush?” offered O’Donnell.

“No, that’s not it. What was I thinking of?”

“A bromance?” asked King.

“Yes! That is it!” Rose said, his curiosity about contemporary slang apparently satisfied. “A bromance.”