Fledgling rapper Lil JoJo’s dreams of fame and riches ended in the bargain-rate graveyard of choice in Chicago’s endless gang wars.

“Right here,” said groundskeeper Lamar Davis as he raised a sheet of worn plywood from the dirt filled hole that is Grave 1, Row 2, Lot 63, Block B, Section 30 at Mount Hope Cemetery.

The tombstone, if the family has the means and the inclination to purchase one, will be inscribed with the name by which his loved ones knew him, Joseph Coleman. Onlookers say the 18 year old’s funeral procession was typical for a gang-related send-off, with 100 cars or more, the occupants flashing gang signs and the occasional pistol and swerving deliberately into oncoming traffic.

But, however much it resembled the two or three other such gang-related processions a week to Mount Hope, this cortège was unique in the procession of events that preceded it, in its genesis.

Here was a killing that might very well not have been were it not for the serendipitous fame-making powers of the Internet. That, and what appears to be the heedless greed of a big-time recording company, Interscope Records.

It all started on Jan. 2, when somebody posted on the World Star Hip Hop site a 4 minute, 40 second video in which a youngster maybe 6 years old goes wild with joy about somebody named Chief Keef.

“Chief Keef’s out of prison!” the youngster exults.

The youngster shouts and jumps wildly about, reciting lyrics as if rap were pure rhapsody.

“On that gangbanging s--t, this is what I do … Them guns super loud, will shoot a n---a down!”

The video went viral and with that came the question of who exactly was this Chief Keef. He proved to be a 16-year-old Chicago rapper named Keith Cozart who police say is affiliated with the Black Disciples gang. He had indeed been freed after a brief stint on gun charges.

Keef had made a few videos of his own, a number while under house arrest in his grandmother’s residence. These included “3Hunna,” with 300 being a reference to the Black Disciples.

His videos, in turn, went viral and there was big buzz on the Internet about this newcomer talent, his charisma, his screen presence, his tingle of real danger. One of his videos, “I Don’t Like,” would eventually score more than 16 million hits on YouTube.

Kanye West did a remix of “I Don’t Like.” A number of recording companies are said to have approached Keef, unperturbed by the gang-related lyrics and images at a time when the rising murder rate in Chicago was getting national attention. He decided on Interscope, reportedly signing a contract for $3 million plus a bio pic.

“[Interscope] was talking good to me,” he was quoted telling MTV’s RapFix. “They was talking like I was talking and I liked that.”

From the turf of another gang just three blocks away, Lil JoJo apparently decided to seek his own fame and fortune by starting a rap feud with Keef in the East Coast—West Coast style of Biggie Smalls and Tupac.

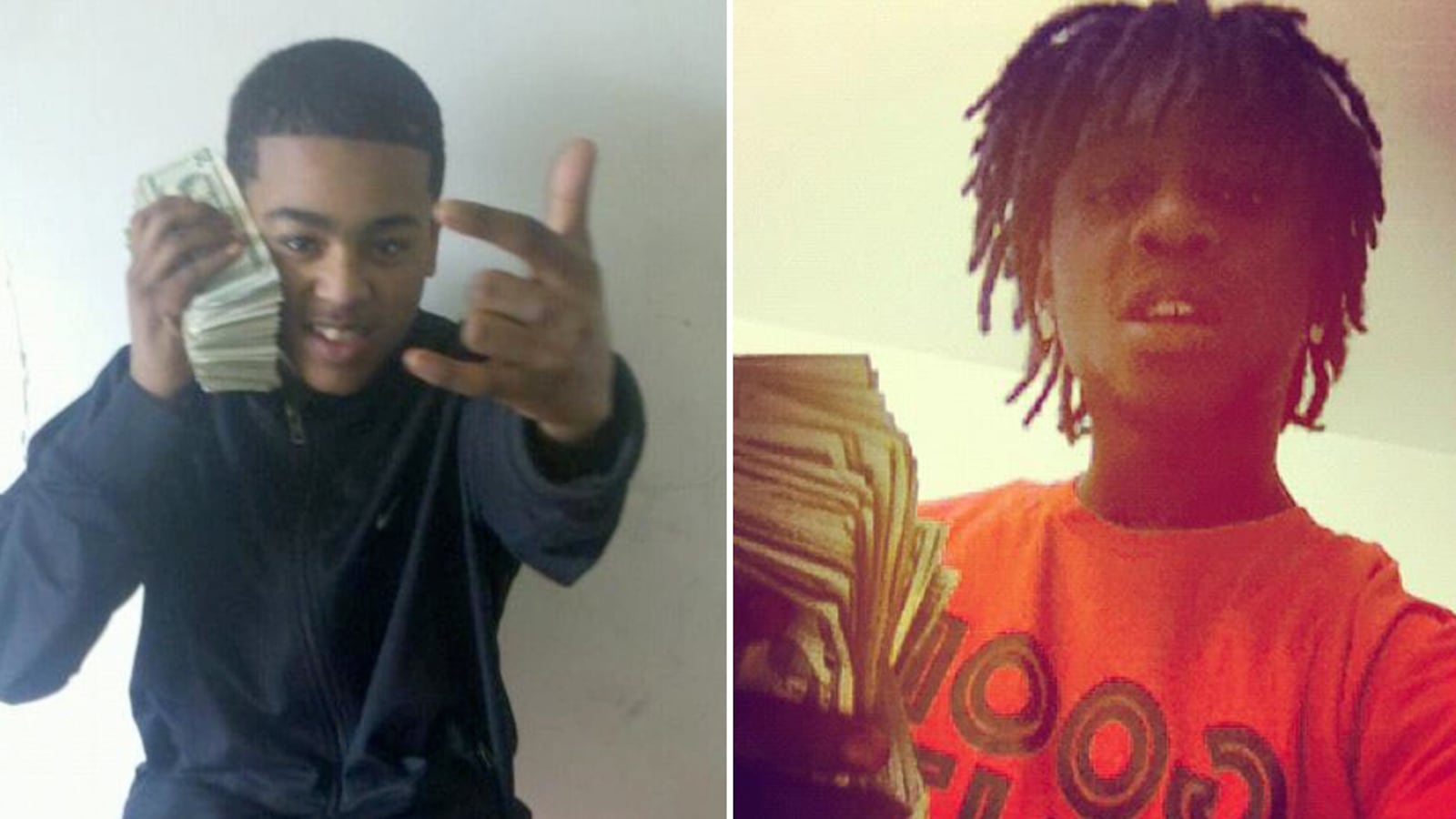

JoJo began posting videos, including “3HunnaK,” adding the letter “K” to the title of Keef’s apparent homage to the Black Disciples, the K standing for “killer.” Police say that Lil JoJo was affiliated with the rival Gangster Disciples. The footage shows an impossibly young looking JoJo and his buddies waving various firearms to the beat, including a Tech 9 and an AK 47.

“These n---as claim 300, but we BDK,” they chant, using gang shorthand for Black Disciple killers.

On top of that, JoJo’s brother, Cashout, posted a video of himself calling Keef’s mother, with him leering at the camera as her voice crackles over speaker phone.

At 4:04 p.m. on Sept. 4, JoJo posted a video of himself and his comrades driving into Keef’s territory. It recorded them shouting insults at one of Keef’s best buddies, Lil Reese.

“I’m a kill you!” somebody can be heard saying in reply and this was not just some rap lyric.

As evening neared, JoJo announced over Twitter that he was on 69th Street. He was riding on a friend’s bike, standing on the rear pegs, at 7:30 p.m., when a tan Ford Taurus pulled up and somebody began shooting. JoJo fell mortally wounded.

In the immediate aftermath, Keef tweeted, “Its Sad Cuz Dat Nigg-a JoJo Wanted to be Jus Like Us #LMAO,” the Internet shorthand for Laughing My Ass Off.

Nobody in cyberspace had seemed much bothered that Keef rapped about gangs and guns, but mocking a dead teen sparked Internet outrage, including among his 240,000 Twitter followers. There was even talk that Interscope might cancel his contract.

Keef, now 17 and sporting a watch said to cost $50,000, denied sending the mocking tweet.

“My Twitter acct was hacked,” he tweeted, saying of Lil JoJo, “i didn’t know him but he was young just like me. I can assure everyone that I had nothing to do with this tragedy.”

Keef declined to make any direct comment to The Daily Beast.

“He only gives interviews when he is guaranteed the cover,” said a caller who identified himself as Keef’s manager.

Keef’s grandmother, 63-year-old Margaret Carter, an upstanding school bus driver, insisted to me that her grandson was interested in “shopping and girls,” not gangs.

“If he doing gangbanging, he is very, very good at hiding it from me,” she said.

Keef might be interested to hear that she also said her appearances in the videos he made in her home were cinema verité when it came to her appearances.

“When I said, ‘Get out of my dining room,’ that was real,” she reported.

At Lil JoJo’s wake, so many fans and gang members surged in for a last look that they nearly tipped over the coffin. His mother, Robin Russell, had to call out "Back up!"

Outside in the funeral home parking lot, somebody blasted Lil JoJo’s “3HunnaK,” and some of the younger mourners began dancing, rapping along with the murdered teen.

“BDK!… BDK!”

The funeral procession became the latest to roll through the tight-knit, working-class neighborhood surrounding Mount Hope, where residents have traditionally paused to pay their respects whenever a hearse passes.

“You bow your head and you pray for that deceased person,” says Kathleen Walsh.

But of late there have been so many gang-related processions, some 100 a year, that the residents have become fearful somebody will be struck by a car or hit by a stray bullet. Those who once bowed their heads are now raising their voices to demand greater oversight and a new cemetery entrance to facilitate a more orderly arrival. Walsh and fellow resident Tony Bansley organized a peaceful protest by more than 200 on a recent Saturday.

“We are not trying to get in the way of anybody mourning,” Bansley says. “This is a valid public safety issue.”

Bansley has been compiling incident reports of the some 100 gang-related funeral processions to Mount Hope a year. Lil JoJo’s cortège led Bansley to add reports of shots fired, the recovery of a loaded .45 automatic, and numerous instances of dangerously reckless driving.

At the graveside, the ritual became too much like any young person’s funeral as Lil JoJo’s mother crumpled in grief. The prayers were led by Corey Brooks, the famed “Rooftop Preacher” who once spent 94 days living atop a derelict motel to dramatize the need for a community center and who walked 3,400 miles across America to raise money for efforts to curtail violence. But words of peace are hard pressed to compete with a record company that can put up $3 million for words of inner-city war.

Among the cemetery workers in attendance was Lamar Davis, who is from the same neighborhood as Lil JoJo. Davis has been working at Mount Hope for 12 of his 28 years and he has buried more than enough young people of his acquaintance to perpetually reconfirm his wisdom in choosing honest toil over the streets.

“I’m glad I work here,” he says.

After the grave was filled, the groundskeeping crew covered it with plywood. Davis said the next step would be to plant grass seed on the surrounding expanse of barren ground.

“Then the grass starts growing,” he added.

But with summer gone and winter approaching that may have to wait until a spring that Lil JoJo will never see. The spring will also bring something for Davis.

“I got my first child on the way,” he is happy to report.