BEIJING— As the controversy surrounding the blind rights lawyer Chen Guangcheng continues to roil Sino-U.S. relations and dominate headlines in the foreign media, the dissident on Friday denied seeking political asylum and stated he merely wants to attend New York University, which it was announced had offered him a fellowship. China’s Foreign Ministry then released a two-sentence statement saying that he can apply to study abroad, just like any other Chinese citizen.

In a press conference in Beijing on Friday evening, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton responded to the developments, telling reporters “progress has been made today over the future that Chen wants, and we will stay in touch with him."

These are the most recent twists in a careening saga that has ensnared the Obama administration and the Chinese government in a tense standoff over the fate of one man.

Yet most Chinese remain blissfully unaware of his plight and its diplomatic impact.

That ignorance is by design. A search for Chen’s name on China’s largest microblog, Sina Weibo, comes back with this enigmatic response: “According to Chinese laws, regulations and policies, the search results about ‘Chen Guangcheng’ are not shown.”

Until Friday, Chinese citizens were given little to no information about their compatriot or his daring escape from extralegal house arrest. Conspicuously absent from the Chinese media was any account of the abuse he endured while a prisoner in his own home, let alone a mention of his legal advocacy on behalf of thousands of peasants who have been beaten, sterilized and forced to undergo abortions by Shandong province officials.

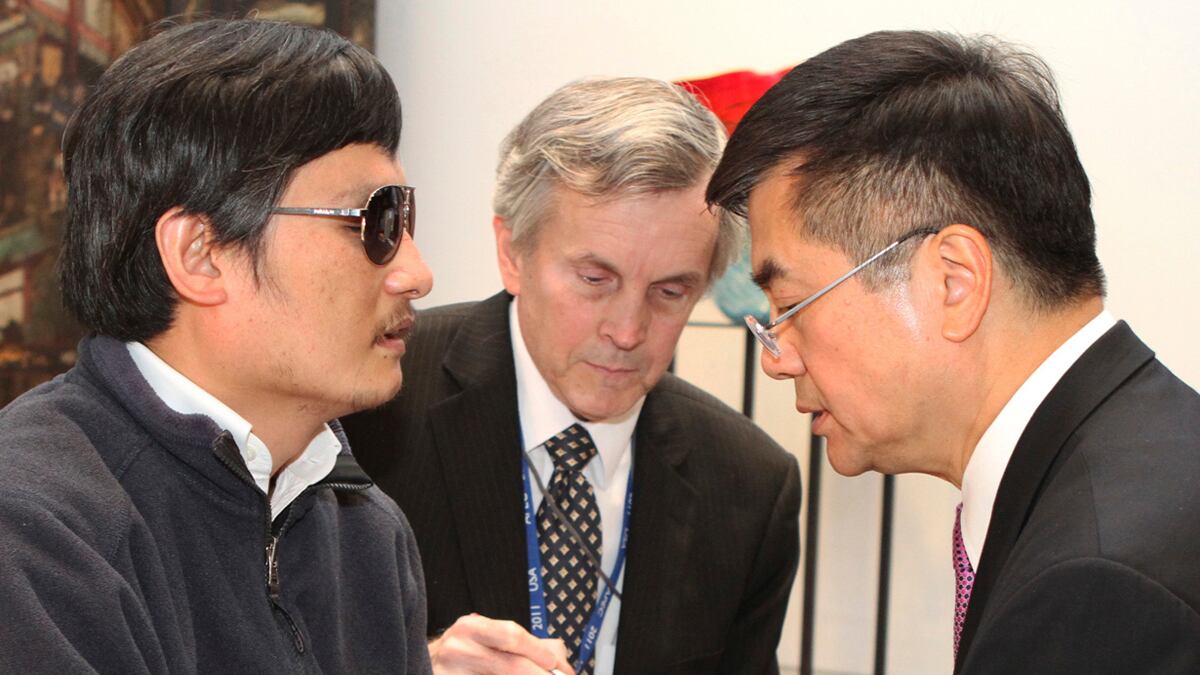

When word hit Twitter that Chen had reached an agreement with the Chinese government to leave the embassy on Wednesday, reporters massed at Beijing’s Chaoyang hospital to watch him arrive with U.S. Ambassador Gary Locke for what was supposed to be a joyous reunion with his wife and children. At first China’s state media reported the event, saying he had left the embassy of his "own volition." His name was visible again on Weibo. The prospect of Chen living as a free man in his homeland looked good.

Until the agreement unraveled, within hours. Left alone in a hospital room surrounded by Chinese agents, he began to have second thoughts about his fate. He then asked for asylum in the United States, telling The Daily Beast he wanted safe passage aboard Hillary Clinton’s plane. China’s propaganda wardens began having second thoughts too. Soon “Chen Guangcheng” vanished once again behind the censors’ online walls. The rapidly evolving situation has kept the censors racing to block each new development from the eyes of Chinese citizens, one word at a time.

Today, Chen is unsearchable on Weibo, as is any language that might refer to the case. Wondering about the quality of doctors at Chaoyang Hospital? Find another way of describing that esteemed medical institution. Curious about who represents the United States in China? “Gary Locke” is banned. Same goes for “U.S. Embassy,” and that most subversive of international relations lingo: “political asylum.”

China’s efforts to stifle online discourse among its citizens has long caught their more creative wordplay in its grasp. In Chen’s case, various iterations with the same meaning have been scrubbed from the digital ether. These includes what sounds like a morbid commentary on the plight of many Chinese rights activists—“Frozen Corpse Bone”—but is actually a homophone for Chen’s hometown, Dongshigu, where he was kept locked away in his stone farmhouse for 20 months.

The censors, nimble as ever, have largely accomplished their goal.

While a diverse group of Chinese activists and China watchers hunt for the latest breaking news about Chen beyond China’s Great Firewall, the rest of China is clueless.

Asked about Chen Guangcheng on Friday, a student at Peking University—China’s equivalent to Yale—furrowed his brow, blinked and replied “Who’s that?” Other students had the same confused reaction.

The complete information blackout on Chen Guangcheng is rife with metaphor. Call it a case of the blind leading the blind: a man who lost his sight as an infant can perceive the matrix of unceasing controls while those with working eyes see nothing and know less.

At some level, the Chinese government is aware of the Kafkaesque nature of the Chen case, made only more absurd by an official damage-control policy familiar the world over: deny, deny, deny. But in China, where truth is often wiped out by the official version of reality, that strategy yields spectacularly efficient results.

To wit: on Thursday, a Foreign Ministry spokesman claimed that Chen was never, ever kept under house arrest, despite obvious evidence to the contrary. “After Chen Guangcheng was released from prison, he is a free person as far as I know. He has been living in his own house,” said the spokesman.

When journalists challenged him on that inaccurate fact, he stuck to his government-crafted script. “As far as I know, he’s living in his hometown,” he said.

In the official Chinese account of Chen Guangcheng, the hero and villain roles are reversed. An article in the state-run Global Times newspaper portrays Chen as a criminal who “resorted to extreme and violent ways.” His crime? “According to the local government, he led some people to smash a police car,” the article states. Keep in mind that at the time of the incident, Chen was already under house arrest for calling attention to the local government’s practice of forced sterilizations and abortions.

Rather than acknowledging the brutal treatment of Chen and his family, China is trying to shift the blame. “Reports of Western media on Chen are simple and monotonous, mostly centering on how he was beaten, imprisoned, and silenced,” the article said. “Chen's case has been hyped as a dark reflection of China.”

So in other words, the Chinese government is the victim. And who, then, is the oppressor? A "backpack-wearing, Starbucks-sipping troublemaker"—also known as Ambassador Gary Locke, according to an editorial in the Communist Party mouthpiece The Beijing Daily.

Ambassador Locke was photographed last year flying economy class and buying Starbucks coffee with coupons. The photos went viral on Weibo, where Chinese marveled at a high-ranking official behaving like an average citizen, rather than a privileged member of the nobility. China’s propagandists are spinning that incident as a subversive plot.

"Ever since he flew in economy class, carrying his own backpack and buying coffee with coupons, putting on a charade of being a regular guy, what we have seen is not an ambassador to China who is prudent in his words and actions, but a standard-issue American politician who goes out of his way to stir up conflict," The Beijing Daily editorial said.

Attempting to convince readers across the globe—and particularly Americans, the editorial compared Chen’s desperate flight from unlawful house arrest to the U.S. Embassy to a fictional case where Occupy Wall Street protestors were allowed refuge in a foreign embassy.

Consider, first, the Chinese government’s level of tolerance for those who gather in the streets to demand political and economic justice. How safe would those protesters be in a Chinese embassy? Just ask Chen Guangcheng.