The Gucci Museo in Florence is less than two years old, but already it’s been established as a mecca of modern art in a city defined by its Renaissance heritage. In addition to the permanent exhibition of archival pieces—which, by the way, includes a 1979 Gucci Cadillac Seville—the museum has presented solo shows of some of the world’s most established contemporary artists, including video artist Bill Viola (whose exhibition opened the museum in September 2011), British sculptor Paul Fryer, and now, American artist Cindy Sherman.

Cindy Sherman: Early Works, which opened there this week, offers a rare snapshot of the work from the artist’s formative years in Buffalo in the mid-’70s. The selection comes from the private collection of Francois Pinault of PPR (the Gucci Group’s umbrella brand), who is renowned for his extensive collection of modern art, much of which is housed in the Palazzo Grassi and the Punta della Dogana in Venice.

“He is a true follower of what is happening in contemporary art today,” Gucci Museo curator Francesca Amfitheatrof said at the press preview yesterday. “And he has an incredible selection of Cindy Sherman works. He’s a complete fanatical believer in her work throughout different stages of her career.”

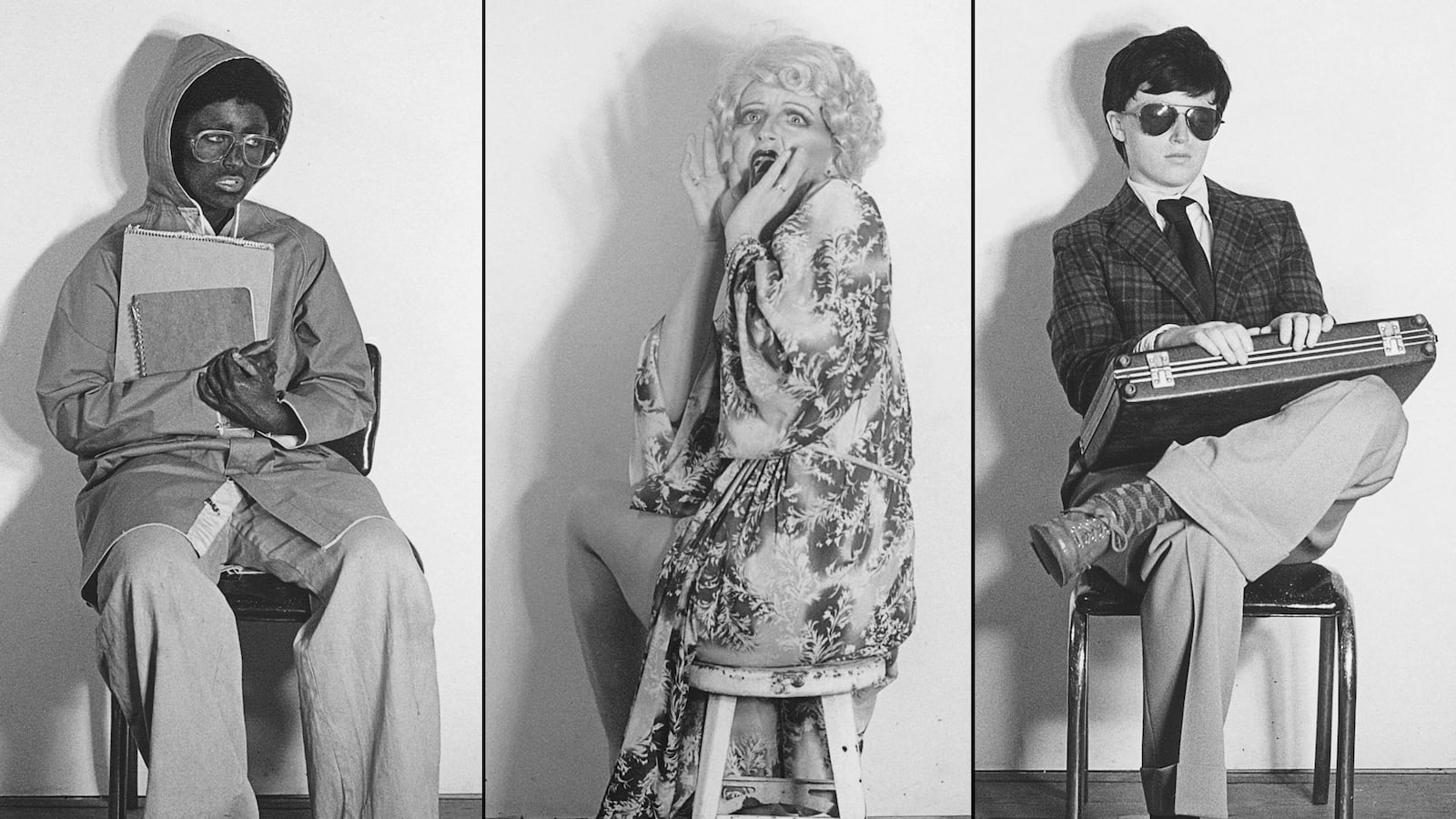

On display are three bodies of Sherman’s work: a short film, Dollhouse, and two photographic series, Murder Mystery and Bus Riders. The work comes from her final year at Buffalo University and her first year after graduation when, along with a group of fellow artists, she established an artist commune and gallery space called Hallwalls.

“They had three exhibition rooms: photography, studio, a film room and a library, and it was a very vibrant moment in the ’70s when artists, on their own steam, would put on a shows,” explains Amfitheatrof. “In New York at the time there was such a vibrant art scene, so they [the Hallwalls commune] felt a bit like they were in the middle of nowhere. But they would invite people like Bruce Nauman and Bob Irving, Vito Acconci to come and visit, and they would spend 10 days lecturing, chatting, and working with them. For someone like Cindy Sherman, it just opened up the whole world of performance and conceptual art that wasn’t about technique: it was really about the idea.”

The body of work on display is evidence of Sherman’s longstanding fascination with gender and identity, themes that became integral to her work. In the black-and-white stop-motion animation Dollhouse, Sherman casts herself as a cutout doll from a book. Wearing only underwear, she searches for something to wear from the clothing featured on the other pages of the book. She eventually settles on a dress that she attaches to her body using paper hooks, but almost immediately an oversize human hand appears in the frame and snatches the dress from her, returning her two-dimensional form back into the pages of the book. “This sort of society putting her back in her place,” says Amfitheatrof. “So it’s extremely endearing and natural and real and honest, but risky as well.”

The prints from both the Murder Mystery series and the Bus Riders series were lost or discarded after they were exhibited in the late ’70s. The former, originally 250 photographs, was created as a film noir–style narrative in which Sherman plays different characters, with the plot unfolding in a series of frames. In Bus Riders, Sherman re-created every day characters that rode the Metro Bus 535 in Buffalo—the pimply teenager, the grandmother, the working woman—and photographed them in various “bus travel” posses. In the year 2000, Sherman reprinted a limited number of these images and Mr. Pinault was lucky enough to get his hands on them.

The two photographic series show many crucial developments in Sherman’s career. “What’s amazing [in this work] is that she evolves from an art student into this incredible artist,” Amfitheatrof says, “and she does it by doing the following: she chooses photography as a medium; she uses herself as a canvas, and then she realises that she doesn’t need to narrate stories—she can put the whole story all in one image.”

It was not long after she completed this work that Sherman moved to New York and began the Untitled Film Stills series that ultimately launched her career. In these earlier works, however, one can certainly already see the makings of a master. “I don’t know anyone else that can transform the environment and themselves so subtlety without it being about pure feminism—it isn’t aggressive,” agrees Amfitheatrof. “You always think that something is going to happen, you know? Is this sad? Is this ironic? The viewer asks questions, which is exactly what an artist should be encouraging.”

For future exhibitions, Amfitheatrof says that they won’t be limiting themselves to solo artist shows. “It’s important that one show follows the other. This isn’t just about one similar exhibition: we are starting a dialogue with the city. And, in a way, doing these shows in Florence is ideal because Florence is surrounded by art from the past. So it has a different function.”