I’m picking up my son, Primo, at his preschool later for a two-night stay with us, and that means one thing: it’s time for a visit to the Coinstar machine. I need to stock up on his favorite yogurt, milk, cereal, eggs, apple juice, and a blue bag of Pirate’s Booty. The pantry at home is pretty well supplied thanks to the big shopping trip we made the last time I got a check, but these are Primo’s staples. They are part of his routine when he is with me, and I do everything I can to store them in. Including scouring the closets and the kitchen drawers for forgotten change, collecting what I can find in a Ziploc sandwich bag, and carrying my stash to Coinstar—or the Penny Arcade; both accept the tiniest offerings, however tarnished, and redeem them into legal tender—for food money. I have no shame when it comes to resorting to the people’s ATM. Perhaps I should. Until recently I had much higher standards for turning in change, waiting, at least, until my proceeds broke the $20 mark, but I’ve been going through one of those periods of late when I can’t afford to maintain even that small dignity. I take what I have, calculating in my head what I’ll need to buy each of Primo’s staples, pour my baggie into the collecting tray, and hope for the best. The lowest I have gone so far is $8.41. That bought Primo’s yogurt and a giant carrot, with a little left over for coffee. (I knew it was going to be bad, so I didn’t bring him with me.) The cashier gave a little smirk when she saw the measly figure on my slip, but I didn’t let it bother me. Coinstar is my miracle slot machine, a movable green altar to prosperity (at a 9.8 cent sacrifice for every dollar), and I have never been unhappy with my winnings.

I realize that I’m long past the age and the station in life where it’s acceptable to carry around baggies of loose change. Tipping the tray into Coinstar and hearing the telltale rattle as the counter spins is not providing. It’s not even getting by. It’s losing. If I polled a sample of the people who I’m closest to, I wonder how many of them have had to redeem change for calories within the calendar year. And out of those who have resorted to Coinstar for a meal, how many would admit it? I know that my father, who has considered being broke a protest vote against the American Dream for most of his life, would never submit himself to Coinstar. He would rather die than sift his coins into the belly of a beast that ate 9.8 percent of what he’d dropped in, and in front of everyone in the supermarket, too. Certainly my grandmother, a lifelong saver of coins, buttons, sugar packets, mini shampoo bottles, and anything else of value would disapprove of cashing in my change for short-term gain when I could sock it away and let it accumulate in the bank at interest. Eventually, I could use that same money to open a five-year CD—and then I’d really be living the dream of every hardworking Greek immigrant. Nana, wherever you are, and I hope it’s at the reception desk of a nice office nestled on a fair-weather cloud over the Aegean: I’m sorry to embarrass you by bringing this up. It’s not your fault. I should have saved the five-dollar bills we got from you every Christmas in envelopes from the bank with an oval cut out to show off Lincoln’s portrait, the ones you took down from the mantel with so much pride, instead of blowing my money as soon as I could on video games and Cheetos. By now, I could be feeding Primo with it. That would have made you happy, and it also would have saved me the task of trying to wash the bitter smell of change from my hands in a preschool bathroom just the other day while Annabel, one of Primo’s classmates, slipped inside the stall behind me to pee.

“You’re Primo’s daddy,” she said behind the stall door.

“That’s right,” I said. “And you’re Annabel.”

“Why are you in here?”

“I’m washing my hands.”

“I can do that.”

“I bet you can. Once I’m all clean and dry, I’m taking Primo home.”

“I’m peeing!”

Early in my relationship with my girlfriend Eliza, while I was teaching at two universities for $9,000 total in salary, finishing up a ghostwriting job for a Christian oilman that had kept me afloat for the year, trying everything in my power not to beg or borrow another dollar from anyone I knew and visiting Coinstar when I needed a quick fix, I found this post on Facebook by a journalist who specialized in celebrity profiles for a big glossy magazine. I had friended her in the big initial flurry of activity after I’d signed up, when I was trying to reach a personal milestone—one hundred or two hundred friends, I don’t remember which—and I am pretty sure that we’ve never met in person.

It was Valentine’s Day weekend. Eliza was staying in a rented carriage house on an alley behind the main drag in Hudson, New York, a town I have always loved for its dissolute charm. She had only a few months left before she had to deliver a draft of her first novel to its publisher, so she had packed her library in a duffel bag, put her cat in his carrier and smuggled him aboard Amtrak to the Hudson Valley for a working holiday. Primo was with his mother and her boyfriend that weekend, so I had left the city and driven up to join Eliza in Hudson. I had just enough money for a full tank of gas, a Valentine’s Day dinner for the two of us and coffee in the morning. I’d be cutting it close, though, and if the restaurant was too pricey, there was a risk that I wouldn’t have enough gas to get me home to Brooklyn. I was a prisoner of my own scarcity, as per usual. It wasn’t as bad as the time, late that previous fall, when I had found myself in Midtown with nothing left in my wallet, no money on my MetroCard, and no way of getting home except to ask a stranger for a swipe at the turnstile for the F train, or make the long trip home on foot. (I walked from 53rd Street to Park Slope, across the Brooklyn Bridge, in something like two and a half hours. I had to take it slow. Blisters.)

So you’ll understand, maybe, why I was immediately taken in by the thread on Facebook, when I saw it, devoted to the question of what the celebrity journalist should do with her “old change.” I could see the vase on her dresser, one of the thin glass globes, I imagined, that come free with flower arrangements. It was full to the rim. Perhaps a little of her change had spilled over the mouth, leaving a halo around the globe of scattered riches; the layering of copper and nickel inside the vase would be undulating, like a desert rock formation, or a painting. I was almost breathless at my laptop, upstairs in the bedroom of the carriage house while Eliza worked on her novel a floor below. This was urgent. I knew what the celebrity journalist had to do. But someone else—a smiling man with a goatee—had already stepped in.

Never seen one in NYC? Anybody know if such a thing exists? My heart sank. It seemed impossible. It couldn’t be true. But then I read the celebrity journalist’s opening post about her change again and checked her other recent posts, most about the musicals and other classic films she was watching, and I had to admit it: she sounded sincere. Maybe she was blessed, or incredibly hard-working, or so resourceful that it hadn’t ever come to turning in her pocket change for groceries. Maybe she glided through her days on the upper tiers of currency and only used quarters for parking meters, tipping baristas, gumball machines. Then there was the alternative: the celebrity journalist needed the change, and the breezy tone of her initial post had been calculated to make it seem as if she didn’t. In either case, from the time of the celebrity journalist’s first post on Facebook asking the hive for advice about what to do with her change, it had taken only two minutes for her to get her first reply from the smiling man with the goatee. Two minutes. And more poured in from there. Despite the arm’s length approach to Coinstar (“one of those machines at the supermarket”), I did feel partially vindicated. At least I wasn’t the only person reading the thread who had a highly developed relationship to my pocket change.

Ask your parents? I thought. Really? You don’t need to ask your parents in New Jersey. I may not use emoticons or write in all lowercase or sing to my barista about how I broke my piggy bank, but I can tell you, the celebrity journalist and the rest of her Facebook friends the precise location of every bank branch with a Penny Arcade below Fourteenth Street, and a few more above that boundary too. They are trail markers for me, signposts for helping to navigate a city—and a life—that runs on lucre and all that it can purchase. My heart kept up its pitter-patter as I continued reading down the thread. I could hear Eliza downstairs, filling up another kettle for tea.

The post had been written by one of New York’s media elite. He had been the editor of major magazines, founded Internet start-ups, written opinion columns on politics and culture and technology, published novels for large advances that made it to the bestseller list. I didn’t know the media insider personally, not well enough to call him a friend anywhere but on Facebook. He was as much of a mystery to me in life as the celebrity journalist. My ex-wife Marina had worked with him for a while on the relaunch of a design magazine, and we had been invited to the same dinner party once. This was back in flusher days. I was still working for the nonprofit and had visions, on my good days, of finishing the novel in a sudden flurry of inspiration and selling it for six-figures. Marina was consulting for the magazine and waiting for her book to meet the world. It was a good memory, what I could recall from that dinner party: bagna cauda bubbled in a fondue pot on the coffee table, the wine flowed freely, we talked of restaurants and the upcoming presidential election and current writing projects and gentrification worries. The stuff of media professionals and opinion makers, people who weren’t busy counting their own change. I have to admit, the media insider’s post on Facebook bothered me. It spoiled my afternoon. I shut my laptop. I stood by the window and looked down on the little backyard behind the carriage house, with its flattened gardens, empty clothesline, and footprints in the snow. I am not often envious, no matter how low into the negative my bank account dips. Envy, of all the Cardinal Sins, comes about as naturally to me as anger and greed do, which is hardly at all. But I couldn’t help thinking, while I stood at the window, of the media insider’s gazillion coins jingling in the bank lobby and how nice it must have been to need reminding of the childlike excitement, the innocent pleasure, that comes from being rich.

Thanks to an unexpected bounty of change from a jar in Eliza’s office I decide to hit the Penny Arcade and to bring Primo with me. By all rights, visiting the Penny Arcade with a four-year-old should be a scene right out Mayberry. We’ll waltz into the bank branch with our bag of coins, use the counting machine to tally up our savings, stand in line together with our slip, the excitement building, and stand in awe at the counter—Primo in my arms, straining to see—while the teller counts out our take in crisp virgin bills and freshly minted change. Mayberry had no banks, however, as squalid and rapacious as mine. There was a time, back when they were new in the market and were trying to make inroads, when coming into a branch was almost a pleasure and sitting down with one of their agents at a shared workspace felt like banking in a more egalitarian country. Like Sweden, if it annexed the population of Queens. I’d opened an account with them to escape an abusive relationship with Chase, which had been fleecing me for years with their service charges and fees. For a while I was happy. My checking account cost me virtually nothing. They cleared deposits the next day, no matter the size or how far the check had traveled. They gave away pens, lollipops, dog biscuits. And then there was Penny Arcade, admittedly a gimmick—I cringed every time the cartoon kid on the touch screen yelled, “Wow, you sure saved a lot of coins!”—but it delivered an implicit message that appealed to me: We don’t care how much or little you earn, where you come from, or how fraught with stress your financial history is. We’ll take your money. You earned it. It has value, even if your last bank turned up its nose at your tarnished change and pushed it back at you through the window in its bulletproof sheathing.

My honeymoon lasted a while, with only minor slippages in fees, transaction charges and customer service. The bank multiplied. Penny Arcade was a breakout hit. So were the bank’s extended hours, which were duplicated by the competition. Then overnight, the bank changed its name. The color signature went from red and blue to green, just green—the color of the same money that it started bleeding from me with $35 overdraft fees. I hate them now. They are indifferent to me, even if, on the day that Primo and I visit the bank branch closest to his pre-school with our sack of coins, they have shaken me down for more than $3,000 in service charges, penalties and interest for the current calendar year. That’s the price the broke pay for playing the zero line, and it’s entirely legal. I have the added insult of having to explain to Primo, on our way inside from the street, what the glowing ad box in the window featuring the smiling, disembodied heads of Regis Philbin and Kelly Ripa means.

“What’s she saying, Daddy?” Primo asks from my arms. I am trying to balance him, a tote bag with books for the subway and after-school snacks, his backpack and our bag full of change, which is in danger of breaking.

“‘Dogs are some of our favorite customers,’” I read aloud from the sign. “See,” I say, pointing my elbow at the bottom of the ad, “that’s a dog biscuit.”

“Why are dogs some of their favorite customers?” he asks, gazing deeply into the ad, as if it holds a great secret. Maybe it does.

“It’s a slogan,” I tell him. “They give out free dog biscuits and put down water bowls in every branch.”

“Why?”

“That’s just what they do, I guess.” He is slipping in my arms, so I bounce him up once to get a better grip around his bottom. The change clanks. “They treat dogs like people, and people like dogs.”

“Daddy!” Primo squeals. He gives me one of those full-faced smiles that travel straight to my lizard brain. The gauze falls over my camera lens. When I look at him in close-up now, he is all soft and shimmery, like a four-year-old romantic lead in an old Hollywood star vehicle.

“All right,” I backtrack. “Maybe they just like dogs.”

“Why do they like dogs, Daddy?”

“Let’s go in and do the change now,” I suggest.

“I don’t want to!”

“C’mon, we’re going in.”

The one Penny Arcade machine in working order at the bank that night has seen better days. It is deep inside the branch, near the corridor where tellers have a way of disappearing for long stretches in the middle of a transaction and the regular post for the police officer who stands there looking lost all the time, presumably as a deterrent against bank robberies. The crowd is sparse at that hour. The darkness in the windows lends a middle-of-nowhere feel to the branch. We could be in a mall on the outskirts of Albany, or onboard a spaceship. The customer service desks are all cleared and vacant. There are only a few tellers left, busy doing tallies and ignoring the customers who come in. I put Primo up on the Penny Arcade machine, clearing away some of the day’s debris from the counter first. It reminds me of the seating area of a bus station: hundreds of people must have emptied their vases and Ziploc bags and tea tins and pockets here. I see lint and thread and old subway tokens and bobby pins. I wonder if someone has actually been sleeping on Penny Arcade; could someone just come in and lie down on top of the machine and sleep? It feels, to me, like a place where someone has been sleeping.

Luckily, Primo doesn’t seem to be aware of the human imprint. He just wants to pour the coins into the tray.

“I wanna do it!” he hollers.

“I’m just helping you a little,” I say. “Here.”

“I wanna do it all by myself! No, Daddy!” I let him keep the bag of coins in his lap and spill them out into the collection tray by the handful. That keeps him busy. I follow the steps by tapping on the touch screen, and we’re in business. We shovel in our coins together, listening to them drop into the machine’s gullet, and then I point out to him the display of numbers—a fake version of our tally—spinning on the screen.

“Wow,” Primo says, eyes glued to the numbers. “Look at that!

“I know,” I say. “It’s like a slot machine.”

“Are we getting a lot of money, Daddy?”

“Well, I wouldn’t say a lot.”

“How come?” He sounds disappointed.

“That’s all we have.”

“How come we aren’t getting a lot of money, Daddy? How come?”

“We have plenty for groceries,” I say. “And you know what? We’re getting you a bag of Pirate’s Booty.”

I pick him up off the coin machine and he tries to squirm away, keeping his head turned to watch the numbers spinning on the screen. It is the end of a school day; he is tired, probably hungry, and in one of his edgy, borderline cranky moods.

Primo doesn’t often stump me with his questions. No matter what he asks, whether it’s the constant volley of “whys?” that help him learn about the world, or any one of the odd technical questions that arrive out of nowhere (“What’s fluoride, Daddy?”), I usually have some kind of answer for him, even if it’s incomplete or turns out to be wrong when I think of it later and resort to Google. He stumped me the first time he ever memorized a joke (Primo: “How does a pig shovel gravel?” Daddy: “Let me see. I don’t know. How does a pig shovel gravel?” Primo: “With a shovel!”) and I am sure that many of my answers to his questions about NASCAR engines are useless. But at Penny Arcade, while the last of our borrowed coins rattle through the counter, I find that I have no answer when he asks me why we aren’t getting a lot of money. I can’t tell him how come we don’t have a gazillion in change to cash in, other than the fact that we don’t have it. I am confronted with the reality of being a broke father, and I am reminded of all that I am in danger of losing because of where I am. This makes me gloomy.

Wow, you sure saved a lot of coins! It’s the dickish little mascot, Penny, from the innards of the counting machine again, pretending that it’s on my side while its employer screws me, keeps me coming back for more.

“I wanna go, Daddy,” Primo whines.

“We need to get our slip and wait in line,” I say.

The tears swell in his eyes. “But Daddy! I wanna go!”

And so our outing to the Penny Arcade ended in tears (his), a bruised ego (mine) and a respectable $39.83 haul for groceries. Enough for what I needed that night, but not for what I want—not even close. Besides, I had paid too high a price for the trip in wounded pride. That’s how it works at the Bank of Desperate Times: you walk in with your offering, pour it into the computing machine, and walk away with another debt against your soul’s collateral, another figure to repay at interest. This time I owe my son.

Please, let him not remember.

Let that trip to the Penny Arcade be our last.

Unless it’s for the joy of it. Not because I need to feed him, keep him in milk, yogurt, additive-free turkey bologna.

Let him know what it’s like to have a father who can pay his bills.

Let him never have to ask, once he’s old enough to know the difference:

Daddy, how come you’re always broke?

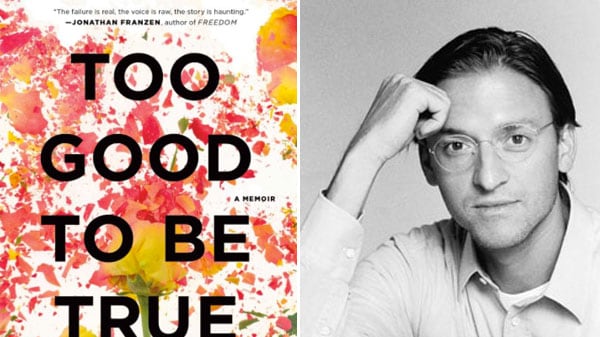

Excerpted from Too Good to Be True by Benjamin Anastas. ©2012 by Benjamin Anastas Published by Amazon Publishing/New Harvest October 2012. All Rights Reserved.