I spent most of my Saturday playing Blackstar, the new album from David Bowie. Late Sunday evening, I was at home, planning my workload for the week. “I want to write something about Bowie,” I thought. But I didn’t want to write a review. Maybe something about his impact on me as a music writer. Maybe something about his decision to withdraw and let his music speak for him in recent years. Maybe about the value of music’s great enigmas. I don’t know what I thought I was going to write, exactly.

But I never thought I’d be writing about the death of David Bowie.

Bowie died late Sunday night after an 18-month battle with cancer. Even after I heard, I couldn’t bring myself to tweet anything remotely close to “RIP David Bowie.” It feels unnatural. It feels inadequate. It feels wrong.

For most of my most favorite artists, I can recite when they crashed into my world and how. I remember the circumstances vividly—like a flash. A friend making a mixtape for me in high school made me aware of Marvin Gaye’s genius almost a decade after his untimely death. Classic-era Stevie Wonder was the soundtrack to the summer I turned 22—after I’d bought Songs in the Key of Life on a whim. I found the Beatles through sheer curiosity a year earlier and became the kind of obsessive fan most people hate. But there are only two such artists who have immeasurably shaped my perspective as a music fan, critic, and aficionado for whom I can’t recount exactly how and why I found them: Prince and David Bowie.

I’d heard Bowie as a kid during his Let’s Dance years, when singles like “Modern Love,” “China Girl,” and the classic title track were impossible to miss. And Bowie’s Labyrinth-era image was burned into my childhood consciousness; he was, after all, Jareth—the baby-stealing goblin king in that famous fantasy from 1986. But it was in my twenties that I really found Bowie. The only specific thing I remember was an ex-girlfriend giving me a compilation CD as a random gift. But I don’t quite recall when I became committed to understanding David Bowie.

There is something about Bowie’s enigmatic persona and creative restlessness that fascinated and intimidated me. His earliest years as a somewhat unremarkable late ’60s singer-songwriter belied the mercurial nature of his muse. His first big hit was the classic novelty “Space Oddity” and it took a while for him to nail down who he was as an artist. But on The Man Who Sold the World, the man born David Jones found his persona and his sound. Drenched in heavier rock sounds and buoyed by his collaboration with guitarist Mick Ronson and producer Tony Visconti, Sold the World is also remembered for his appearance on the cover in a dress. It was the beginning of his gender-bending public image and also a benchmark for glam rock, but Bowie was just getting started.

He subsequently moved from the grandiosity of Hunky Dory to the conceptual marvel that is his most iconic album: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars. The album made Bowie a rock star and his androgynous image took the rebellious long-haired aesthetic of the ’60s and amplified it tenfold. He was pushing buttons and tearing down boundaries. “I’m gay,” he said in a 1972 interview with Melody Maker, just before Ziggy broke big. “And always have been, even when I was David Jones.” The topic of Bowie’s sexuality would be the subject of rumors, contradictions, and clarifications for several years, but it can’t be denied that Bowie’s willingness to broach the topic in the still-very macho world of mainstream rock was groundbreaking only five years after homosexuality was declared no longer illegal in Great Britain.

Musically, he would go on to continue evolving and challenging his audience throughout the 1970s, going on one of the great album runs in popular-music history. Aladdin Sane, Diamond Dogs, Young Americans, Station to Station, Low, Lodger, and Heroes showcase an artist who is creatively restless but never conceptually aimless; Bowie was traveling through his own bevy of ideas, not artistically wandering. Along the way, he gathered an enviable list of collaborators; from Brian Eno to Carlos Alomar to Luther Vandross to John Lennon to Robert Fripp. He wrote and produced for Lou Reed, Mott the Hoople, and Iggy Pop. He began acting—appearing in films like The Man Who Fell to Earth and Just a Gigolo. He also developed a cocaine addiction, and made bizarre claims; he believed Jimmy Page was attempting to possess his soul, thought that witches were trying to steal his semen, and claimed to see Satan in his swimming pool.

By the mid-’70s, Bowie had gone through the glam rock of Ziggy and the soul-funk-influenced sounds of Young Americans. On the cusp of his “Berlin Trilogy,” he’d created his latest character: The Thin White Duke. Gone were the sly grooves and rhythms of Young Americans and Station to Station. Gone was the fire-red hair and androgynous makeup and in its place was a dapper, colder, more conservative image—like Sinatra with a Third Reich fetish.

“You’ve got to have an extreme right front come up and sweep everything off its feet and tidy everything up,” he said in 1975. A year later, he told Cameron Crowe during a Playboy interview that “Television is the most successful fascist, needless to say. Rock stars are fascists, too. Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars.” Bowie would later say that he was drug-addled and saying ridiculous things (when Crowe closed with the question “Do you believe and stand by everything you’ve said?” Bowie responded coyly: “Everything but the inflammatory remarks”), but when he was photographed giving what appeared to be a Nazi salute, his image took another hit and he was cited as a catalyst for the founding of Britain’s Rock Against Racism in 1978. “That didn’t happen… I just waved,” Bowie said at the time. “On the life of my child, I waved.” After he’d moved to West Berlin, Germany, in late 1976, he’d learned more directly about racism and fascism and he renounced any interest in Nazi imagery. “I was out of my mind, totally, completely crazed,” he told Rolling Stone.

In spite of the controversy swirling around The Thin White Duke, the period marked Bowie’s most innovative and arguably, most influential period. From Joy Division to Radiohead, the more avant-garde, industrial, and atmospheric leanings of Bowie’s “Berlin” albums (Low, Lodger, and Heroes) may stand as his most enduring musical legacy. Even if it was born of pain. “Life in L.A. had left me with an overwhelming sense of foreboding,” Bowie told Uncut years later. “I had approached the brink of drug-induced calamity one too many times, and it was essential to take some kind of positive action. For many years Berlin had appealed to me as a sort of sanctuary-like situation.”

Bowie’s shift into pop hits in the 1980s was another unexpected change in both music and persona. In a bit of a more polished update on the soul-funk of Young Americans, Bowie worked with producer Nile Rodgers on the multiplatinum smash Let’s Dance and collaborated with fellow rock legends like Queen and Mick Jagger. The subsequent Serious Moonlight Tour further cemented David Bowie as a megastar in the age of MTV and it was my first experience with his music. And he was still willing to push buttons in interviews. He spoke candidly about MTV’s lack of support for black artists during an interview with network VJ Mark Goodman in 1982.

“There seem to be a lot of black artists making very good videos that I’m surprised aren’t being used on MTV,” Bowie said in the interview.

“We have to try and do what we think not only New York and Los Angeles will appreciate, but also Poughkeepsie or the Midwest,” Goodman responded. “Pick some town in the Midwest which would be scared to death by… a string of other black faces, or black music. We have to play music we think an entire country is going to like, and certainly we’re a rock and roll station.”“Don’t you think it’s a frightening predicament to be in?” Bowie asked.“Yeah, but no less so here than in radio,” said Goodman.Bowie pounced: “Don’t say, ‘Well, it’s not me, it’s them,’” he countered. “Is it not possible it should be a conviction of the station and of the radio stations to be fair… to make the media more integrated?”

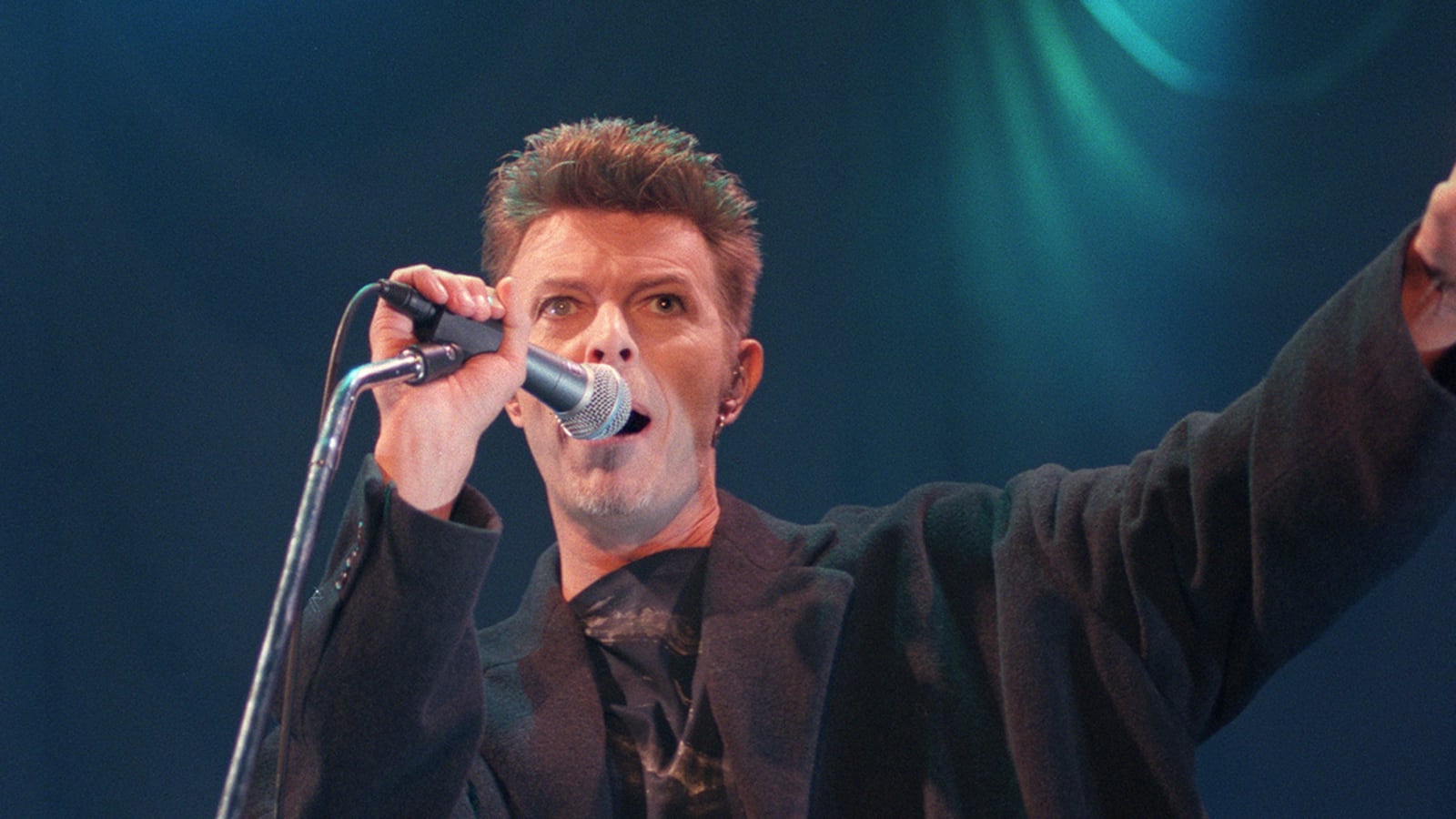

VIDEO: A Tribute to David Bowie

His status as a chart-topper (and more appearances in major films) raised his profile even higher, but it was always clear that Bowie would not be boxed in by anything—least of all, chart success. After ending the 1980s with a few lackluster releases, he regained his creative muse fronting Tin Machine for two albums before releasing Black Tie, White Noise, another collaboration with Nile Rodgers that was informed by his fascination with soul, electronica, and hip-hop. He’d famously married supermodel Iman in 1992 and was living in New York City. He would dabble in everything from industrial to drum ’n’ bass music for the remainder of the ’90s—as mercurial as ever in his mid-fifties. After a heart attack in 2004, he lowered his profile and his output.

But his impact was felt throughout music. Around the time that Bowie was slowing, I was beginning to fully appreciate his influence. I heard Bowie in the melodrama of Arcade Fire. I heard him in the nervous energy of Franz Ferdinand. I heard him in Bloc Party. I heard him in Vampire Weekend. I heard him in Janelle Monae. I heard him in Miguel. I heard David Bowie everywhere. I was glad to hear Bowie return to music with 2013’s The Next Day and blown away by Blackstar just two days ago.

He was complicated and he was confusing. He was ever-changing. And in being such, he was a constant. He loomed large even when we barely saw him. My appreciation for music and its deconstruction was infinitely raised by having heard David Bowie. He inspired me and challenged me to think beyond pop hooks and flashy guitar solos. He was a freak and a weirdo and a provocateur and an innovator and an icon. Even with his mistakes, I would want to be as creatively bold as David Bowie. Maybe he was insincere. Maybe he was manipulative. Maybe we shouldn’t believe artists must bare their souls to touch ours. I don’t know—even now. But I know that I wouldn’t be the appreciator of art and music that I am today without having discovered the genius of David Bowie.