There are few actors as accomplished, or as effortlessly cool, as Delroy Lindo, who for more than three decades has brought a commanding intensity, sharp humor and easygoing magnetism to a wide variety of film, TV and stage roles. That charisma is once again on grand display in Da 5 Bloods, Spike Lee’s Vietnam War film about four vets—played by Lindo, Clarke Peters, Isiah Whitlock Jr. and Norm Lewis—who return to their former battleground to recover both the remains of their dearly departed comrade Stormin’ Norman (Chadwick Boseman) and the millions in gold bars that they buried decades earlier.

With its quartet also accompanied by the son of Lindo’s protagonist (embodied by The Last Black Man in San Francisco’s Jonathan Majors), it’s a wild and sprawling odyssey of oppression, trauma, resistance and brotherhood. And it’s one that, while referencing the likes of Apocalypse Now and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, speaks directly to our tumultuous racial protest-fueled present moment—complete with overt shout-outs to Black Lives Matter and denunciations of President Trump.

At the center of Lee’s epic is Lindo’s Paul, whose severe PTSD is colored with hate—not only for the “Vietcong” he battled during his youth and the white America that sent him to war and then disrespected him upon his return home, but also for himself, as evidenced by the fact that he’s a proud and defiant Trump supporter decked out in a Make America Great Again hat.

For the accomplished 67-year-old actor, it’s an Oscar-caliber performance that’s as surprising as it is vigorous, exuding conflicted anguish, guilt, regret and fury that feels all the more timely amidst the country’s ongoing dialogue about racism and representation. Even in a career of scene-stealing triumphs, from Lee’s Malcolm X and Barry Sonnenfeld’s Get Shorty to Ron Howard’s Ransom, David Mamet’s Heist, and television’s The Good Fight, his latest is a blistering tour de force of pain, suffering and scars that won’t properly heal.

Ahead of the film’s June 12 Netflix debut, we spoke with Lindo about reteaming with Lee for the fourth time, playing a MAGA-supporting African-American veteran, the George Floyd protests, and his recent departure from CBS All Access’ The Good Fight.

This is your fourth collaboration with Spike Lee, but the first in 25 years. What took so long?

My go-to response is, ask Spike! [Laughs] Don’t ask me. I was ready, willing and able. Spike and I had bumped into each other intermittently over the years, and the conversation had always included, “Oh man, we have to do something. I want to work with you again. We should do something.” For whatever reason, it didn’t happen. But if I had to wait 25 years between Clockers and Da 5 Bloods, this was a fantastic one to wait for.

Da 5 Bloods is about prejudice, suffering and togetherness, and all of that—as well as its direct Black Lives Matter and Trump moments—make it feel extremely resonant right now. The film would have been vital regardless, but are you a bit taken aback by just how much it speaks to today?

Unfortunately, I am not surprised. Obviously, none of us could have predicted the country and the world would be in this moment. But my lack of surprise has to do with this horrific tradition of black men and women being murdered by law enforcement in this country. It’s “fortuitous” that these murders have happened in the last month. But unfortunately, I’m not surprised that we find ourselves in this moment, and again, unfortunately, it is making the importance of this film that much more acute. I agree with you—it would have been an important film under any circumstances. Its importance is increased exponentially, really, by virtue of these murders that have happened in the last three weeks. Well, Ahmaud Arbery was murdered back in February. But the exposing of those murders has increased the importance of the film and story exponentially.

What’s your reaction to the George Floyd protests? Are you hopeful that they’ll lead to meaningful change?

Probably the most accurate thing I can say in response to that is, I have a whole host of responses and reactions to what is happening right now that are really complicated for me, and I’m not able to articulate a lot of what I actually feel.

Having said that, I am “hopeful,” given that once again the youth are at the vanguard of the rejection of this status quo. Not only are the youth at the vanguard, but the fact that the movement—the rejection of the status quo—is as diverse as it is. Also, the fact that it seems to have become a global phenomenon—that’s hopeful. And the fact that, as of a couple of nights ago when I happened to be watching MSNBC, I saw these marches occurring in these really small communities in America. Communities in which black people don’t live there necessarily. But these communities are coming out and having their voices be heard. All of those things cause me to be cautiously hopeful. But the fact of the matter is, only time will tell if this is an extraordinary trend of the moment, compared to whether it will elicit substantive change for the future.

Your character, Paul, is a vet wracked by PTSD, as well as a Trump supporter. What is it about Trump that you think appeals to Paul—and was it draining to inhabit a character like that?

No, it was not draining. It was a challenge, absolutely. But in this interview, in this moment, right now, I’m considering your question in the context of the excitement that I felt at the prospect of taking on this part—specifically, the Trumpian piece. The Trumpian piece is connected, actually, to the PTSD, and I’ll try to articulate what I mean by that.

This is a man, Paul, who has experienced significant betrayals and significant losses. The betrayal of the country, when I came back from Vietnam. Rejecting me for my service, which is right in line with what a lot of Vietnam vets experienced, as you know. It is critical to understand that Paul volunteered; he wasn’t drafted. Volunteered, three tours in Vietnam. And in response to my stepping up and serving my country, out of the love of my country, as a young man, I come back and I’m told I’m a baby murderer. I’m rejected. I’m reviled. So that constitutes a huge betrayal.

In the process of creating a biography for Paul, I also placed in a number of other personal betrayals. So we have the large betrayal of the country and the culture, and then we have betrayals that I had suffered—the loss of my wife, the loss of my son. When I say the loss of my son, I mean the fact that the relationship is as fractious as it is. That constitutes a loss, because I cannot interact with my son and express the love that I have for my son in the way that I would like. So those are two very, very deep-seated losses.

The cumulative effect of all that is that this is a man who needs a win. I need a win. And here comes this individual in 2016 who says, “I can make you a winner. I can change your life. I can rearrange things in this country that will serve you positively.” That’s how Paul came to cast that vote in 2016. That’s the “political.”

In addition to that, we have the emotional and psychological effect of the trauma that I’ve experienced in Vietnam, and returning home, and not being able to get the help that I need. And in fact rejecting the help, when in the film Otis says to me, “C’mon man, I want you to come to a group with me,” and I reject it out of hand, “Nah, that’s not for me, man.” The bottom line is, I haven’t gotten the help that I so desperately need. And so this pathology has run rampant throughout my life, and we see the results as the story unfolds in Da 5 Bloods.

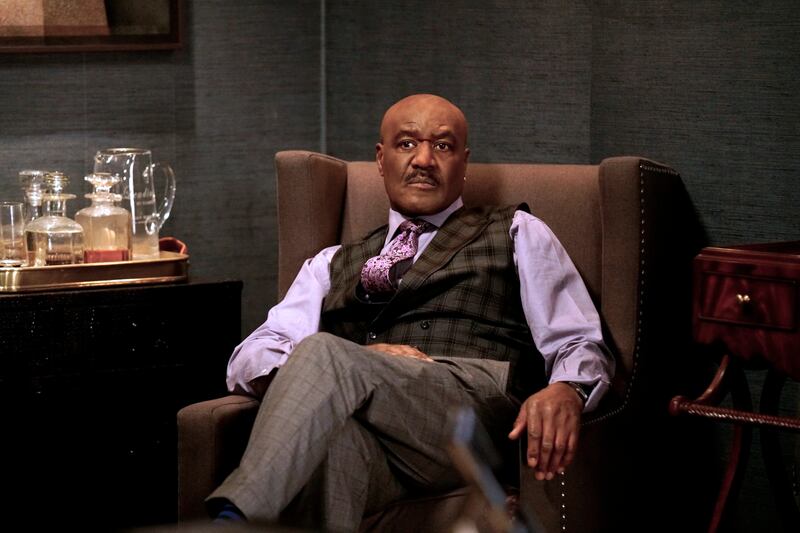

Delroy Lindo and his co-stars in Da 5 Bloods

NetflixPaul’s trauma comes to a head in a late, extended single-take of you in the jungle, which climaxes with your raised fist. It’s a sequence that exemplifies Lee’s ambitiousness, which—I assume—was part of what made the entire project so exciting? It feels like you, and the film, are swinging for the fences there.

Absolutely. Taking big swings, and if I can humbly say, every now and again you hit that thing out of the park, man. There are three runners on base, you’re at the plate, and you hit that thing out of the park and we all come home. And I’m not a baseball fan [Laughs].

The answer is yes, yes, yes, yes and yes again. That speaks to the ambition of Spike. As a co-creative worker on that journey, he creates space for moments like that to happen. Then when those moments happen, and I’m speaking specifically about the raised fist right now, he incorporates it into the film. That’s indicative of the kind of workspace that Spike created on the film, and frankly, in each of the three prior films that I’ve worked with him on. He trusts you. If he trusts you, he’ll give you space. That’s not to say that you can start improvising all over the place. You have to be in service of the story, and the scene. But so long as you’re in service of the story and scene, there’s space for you.

You’re leaving The Good Fight after four years, which I think came as a shock to many. What was the motivation behind that?

First of all, thank you for your shock at the fact that I’m leaving, because what that suggests to me is that you appreciated the work that was done, and the space that Adrian Boseman took up in that story. But yes, I’m going on to do something else. I signed to do a pilot for ABC called Harlem’s Kitchen, which is about an African-American family that runs a restaurant in Harlem.

Delroy Lindo as Adrian Boseman in The Good Fight

Patrick Harbron/CBSWe actually were literally three days away from filming the pilot. I had a break in my The Good Fight schedule, and in that break I was going to do this pilot, and then everything shut down because of COVID-19. Initially, it was supposed to be a two-week shutting down, and then very quickly thereafter, we learned that it’s a shutdown, at that time, for the foreseeable future. I just heard this morning about parts of New York City opening up. I don’t know what that will bode for the future of Harlem’s Kitchen. But I left The Good Fight to go do that show, and hopefully, when New York opens up, I’ll return to Harlem’s Kitchen and explore this family running this restaurant in Harlem. Very different kind of work than The Good Fight, but that’s a good thing. Variety is the spice of life.

You’ve been such an integral part of so many fantastic films, from Get Shorty to Ransom to Broken Arrow to Heist. Is there a key to your career’s diversity—or is doing varied work simply part of the job?

It’s more than a job; it’s absolutely more than a job. And it plays into something that I wanted to do at the very beginning of my career, and something that I did in my theater career, which is to tackle a variety of different kinds of parts, and to try to inhabit different kinds of human beings. Here, with Harlem’s Kitchen, I’m playing a master chef, which is phenomenal—well, a master chef with issues [Laughs], I’ll say that. So yeah, it addresses what I’ve always wanted to do, and what I assume every actor would want to do, and that is to take on a variety of different kinds of work.

Lastly, I’ll just say this. What I’m hoping as a result of Da 5 Bloods is that I will also start engaging feature films more fully than I have been in the last 4-5 years. In addition to Harlem’s Kitchen, I’m hoping very, very, very much that I can re-enter the world of feature films.