As the last model walked off the Christian Dior runway Friday afternoon and the lights dimmed in the stately tent erected in the courtyard of Paris’s Musée Rodin, the audience of more than 1,500 fashion insiders and aficionados stood and cheered.

But why?

It had been less than 72 hours since John Galliano, the creative director of the venerable French brand, had plummeted from grace after allegedly spewing anti-Semitic insults at a couple sitting in a tattered Paris bar, as well as in a jittery amateur videotape sold to a British tabloid. Galliano, 50, was swiftly fired and is now scheduled to go on trial in the spring for racist slurs.

By the time the show ended and the members of the atelier came onto the runway to take their bows, folks were practically ready to weep.

The mood among Dior’s guests that sunny afternoon was sober, with few of the usual fashion peacocks—those flamboyantly dressed eccentrics who provide flashes of color amid the industry professionals in their ascetic navy and black. A 196-foot-long, elevated runway jutted from a dignified backdrop of a mirrored salon—its glass artfully fogged by age—with crystal chandeliers hanging on either side of a wide arch. Gone were the scrums of TV crews battering their way through the crowd, the A-list celebrities who serve as paparazzi bait, the thick cloud of buzz.

As the show began, the first figure on the runway was not some coltish model; rather, it was Sidney Toledano, Dior’s CEO, dressed in a black suit and tie. He stood at the top of the runway and, in French, spoke of the company’s shame and sorrow. With that single gesture, he put a human face on this rarefied brand, one that last year boasted €826 million in revenue. He wrenched your heart. He went on to praise the seamstresses, the fitters, the artisans: “What you are going to see now is the result of the extraordinary, creative, and marvelous efforts of these loyal, hardworking people.”

The collection was charming and coquettish with its silk bloomers, fur-trimmed skirts, ruffled dresses, and sheer lingerie-style gowns. It wasn’t a breathtaking show, but it has been a long time since a Dior ready-to-wear collection made one gasp with pleasure.

What it did do, however, was remind everyone what fashion was before it became thick with theatricality and flamboyance. It was an acknowledgment of fashion as fine clothes. It was a repudiation of everything that Galliano represented.

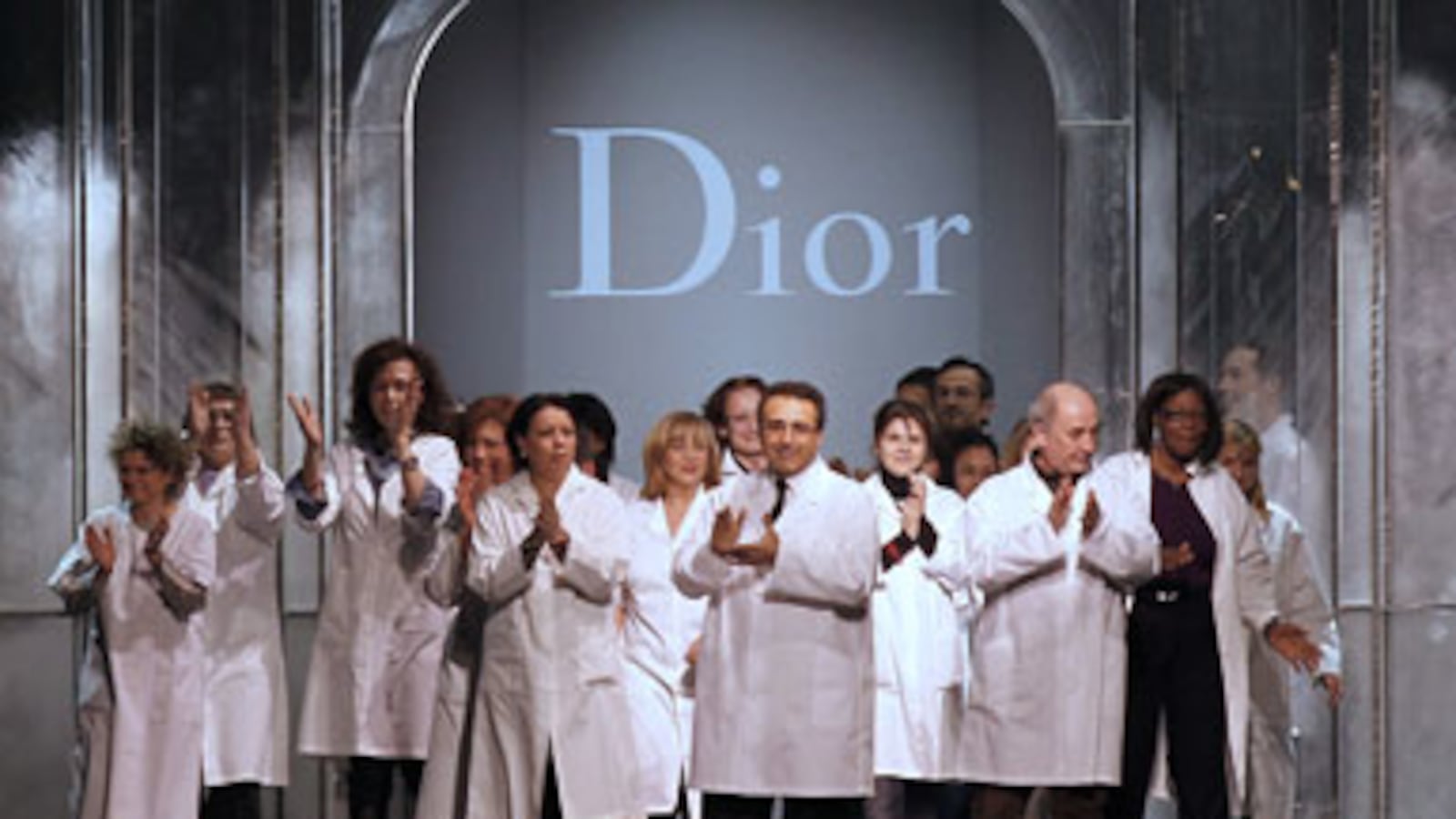

By the time the show ended and the members of the atelier, dressed in their white jackets, came onto the runway to take their bows, folks were practically ready to weep. The audience applauded madly. Someone shouted, “Bravo!”

If it was possible for this global brand to present itself as an intimate, Old World business trafficking in refinement and tradition, the stagecraft of the show did just that. The tightly controlled choreography stirred the emotions while celebrating the unsung heroes of the backroom. But it also left one feeling queasy and distressed about being so easily moved. Who really deserves the tears in this tragedy?

Dior? Did anyone really think it wouldn’t survive?

As a matter of corporate image management, the company handled this scandal brilliantly and could give a few lessons to Hollywood on crisis control. With this perfectly orchestrated show, Dior subtly shifted our attention and reframed the story. Those who usually labor in the shadows received their due. (Certainly, this ghastly episode could not have been easy for these modest men and women.) And now, we are inclined to talk about how the company prevailed, how it survived after a designer brought shame to its doorstep.

• Robin Givhan at John Galliano’s ShowBut last week’s tragedy was human, not corporate. The world watched a talented man’s career decimated at his own hand. (Dior owns 92 percent of the John Galliano brand.) Audiences heard anti-Semitic language at every click of the remote control. The tragedy was that a person who had reached the pinnacle of his creative talent seemingly fell apart alone and angry in a neighborhood bar.

Toledano never uttered Galliano’s name on that runway. It didn’t appear anywhere in the show notes. He had been erased.

It isn’t popular to allow for human fallibility, to admit that people are not perfect in our perfectionist world. But don’t we have to? People don’t implode in a vacuum. Our lives are intricately linked through a shared culture—some of it beautiful, some of it terribly, terribly ugly. This is not a call to excuse Galliano’s behavior or to forgive it. But it shouldn’t be forgotten.

Forgetting would be the greatest tragedy of all.

Robin Givhan is a special correspondent for style and culture for Newsweek and The Daily Beast. In 1995 she became the fashion editor of The Washington Post where she covered the news, trends and business of the international fashion industry. She contributed to Runway Madness, No Sweat: Fashion, Free Trade and the Rights of Garment Workers , and Thirty Ways of Looking at Hillary: Reflections by Women Writers . She is the author, along with The Washington Post photo staff, of Michelle: Her First Year as First Lady . In 2006, she won the Pulitzer Prize in criticism for her fashion coverage. She lives and works in Washington, DC.