Since launching his menswear line in 2001, designer Thom Browne has watched others mimic his shrunken suits—albeit in much less extreme ways—and profit from it. But he has refused to dilute or modify his aesthetic. This was neither good for his business, nor his psyche. “I was just very stubborn,” Browne said. “I wanted to do something that meant something.”

Slowly, however, Browne’s obstinance has begun to pay off. First came the moneymaking moonlighting jobs designing the Black Fleece collection for Brooks Brothers and the Moncler Gamme Bleu line of active sportswear. He recently found a financial investor, Japan-based Cross Company, which will give his signature business greater stability and allow him to expand it.

And Friday afternoon, Browne was fêted by First Lady Michelle Obama at a White House luncheon, where he was one of the 2012 honorees in the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum’s annual awards.

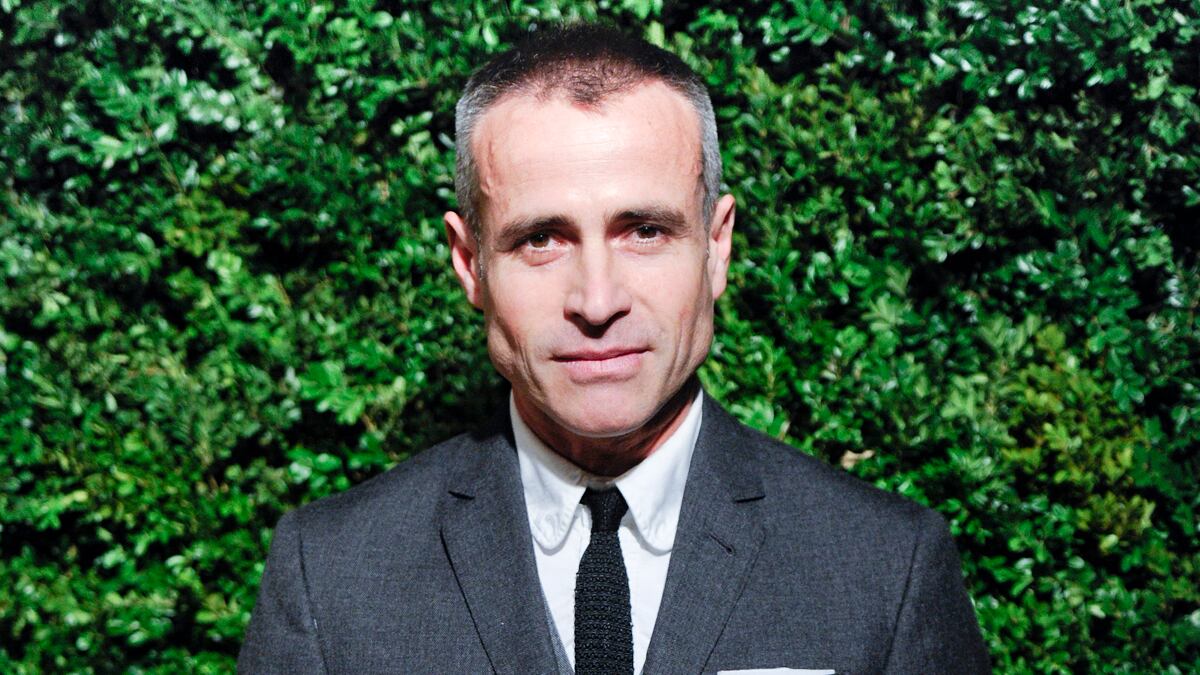

He wore short pants. The slender designer with the angular face chose one of his signature gray business suits that revealed a daring amount of naked ankle.

“Every day, these visionary designers are pushing boundaries, creating and revealing beauty where we least expect it,” Mrs. Obama said in her prepared remarks to an audience that included previous award winners Maria Cornejo, as well as Ruben and Isabelle Toledo. “All of them have done something really good for our country and our world. From the clothes we wear to the technologies we use to the public spaces we enjoy, their work affects just about every aspect of our lives.”

Browne has received all sorts of fashion kudos, but the National Design Award is a particular honor, “because it’s an award alongside other kinds of design,” Browne said. “We all influence and inspire each other, but I’m more inspired by other areas of design, not just fashion.”

“Fashion is more interesting when the references aren’t specifically fashion,” said Browne, who often looks to architecture for motivation. “Even the venues I choose for shows, in terms of the lines, the mid-century architecture, they’re always an influence.”

His brand was born, in part, out of his admiration for the Seagram Building, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, with its 1950s modernist lines. He has looked to New York’s Lever House, another 1950s glass box skyscraper. And when he moved his menswear shows from New York to Paris in June 2010 he chose as a location France’s Communist Party headquarters, with its undulating lines designed by Oscar Niemeyer. It was a fitting backdrop for the Paris debut of his perfectly calculated, spare gray suiting.

From its beginning, Browne’s work established a new menswear message in which grown-up business suits were re-imagined in mini Master of the Universe sizing. He did this at a time when most men resolutely believed that their clothes should be roomy enough to accommodate a village. This boldly shrunken sensibility made him highly influential in the world of menswear but put him at odds with the average guy in middle management.

Browne’s attack on the gray business suit was ruthless. He hacked it off at the ankles. He down-sized the jacket until it resembled something a father might have borrowed from his 12-year-old son’s closet. The clothes were all gray flannel and navy wool, so there was nothing particularly flamboyant about the collection itself. He had simply altered the proportions. And that was enough of a shock. “People didn’t always understand the proportion,” Browne said. “But they understood where I started from. Some people might roll their eyes and say, ‘Are you kidding me?’ But I do start with a classic point of view.”

Browne further muddied the aesthetics by presenting his clothes as elaborate happenings in which models somnambulated through wood-paneled rooms, rode in on horseback or ice-skated around a tiny indoor rink. His dream-like finales featured feathered jackets and evening coats with long, lush trains like something that might be worn by a bride. He toyed with the notion that a man could have plumage and that strutting and preening were wholly in line with the long history of men’s apparel... which they were.

More than any other American menswear designer, Browne has treated fashion as an inter-disciplinary pursuit—one in which a show is both artful happening and literary device. The New York fashion world is receptive to his ideas. But they have been particularly well-received in Europe. “They’re open to so many more provocative ideas of a show being a show instead of a commercially driven” presentation, Browne said.

A native of Allentown, Pennsylvania, there is little in Browne’s background that would suggest he’d become known for such a subversive approach to fashion. Before launching his menswear—and later, a women’s line—Browne tried his hand at acting and also worked for Club Monaco and Polo Ralph Lauren.

Despite his aesthetic eccentricities, Browne is adamant that he is a traditionalist at heart. His designs for Black Fleece, the financial success of which took Brooks Brothers by surprise, are rooted in Ivy League style suits, button-down shirts, V-neck sweaters and cardigans—albeit with his shorter, snugger fit and bolder colors and prints.

“Initially there were sales people questioning the designs and customers questioning,” Browne said. “But then they got new customers. The existing customers even got it because after a couple seasons they got that I wasn’t trying to do something that wasn’t right for the brand. It was all about 1950s, 1960s Brooks Brothers.”

He debuted his Moncler Gamme Bleu collection with a down-filled, gray flannel sport coat.

And for the presentation of his spring 2013 eponymous collection, which he presented in July, futuristic, silver, Slinky-men waddled onto a Paris green. Looking like giant articulated trash cans, each strange creature lined up behind a pair of silver shoes. After each model settled into his footwear, the cylinders slid to the ground to reveal a riotous elaboration on preppy style with madras plaids, whale prints and Bermuda shorts in a chaotic clash of delightful candy colors.

“Creatively, I’m never at a loss for ideas for shows and collections,” Browne said. “It’s been a good challenge to find a way to create a business to back it up.”

A nod of approval from the White House—and a fancy design award—won’t guarantee a healthier bottom line. But after all those years of being greeted by head-scratching and eye-rolling, they are certainly good for the psyche.