Andy Warhol once said, “Good business is the best art.” And while he wasn’t referring to art museums per se, he might as well have been. These days, museums across the country are fighting to stay in the black—and now some of them are asking folks to pay more in property taxes to make up the shortfall.

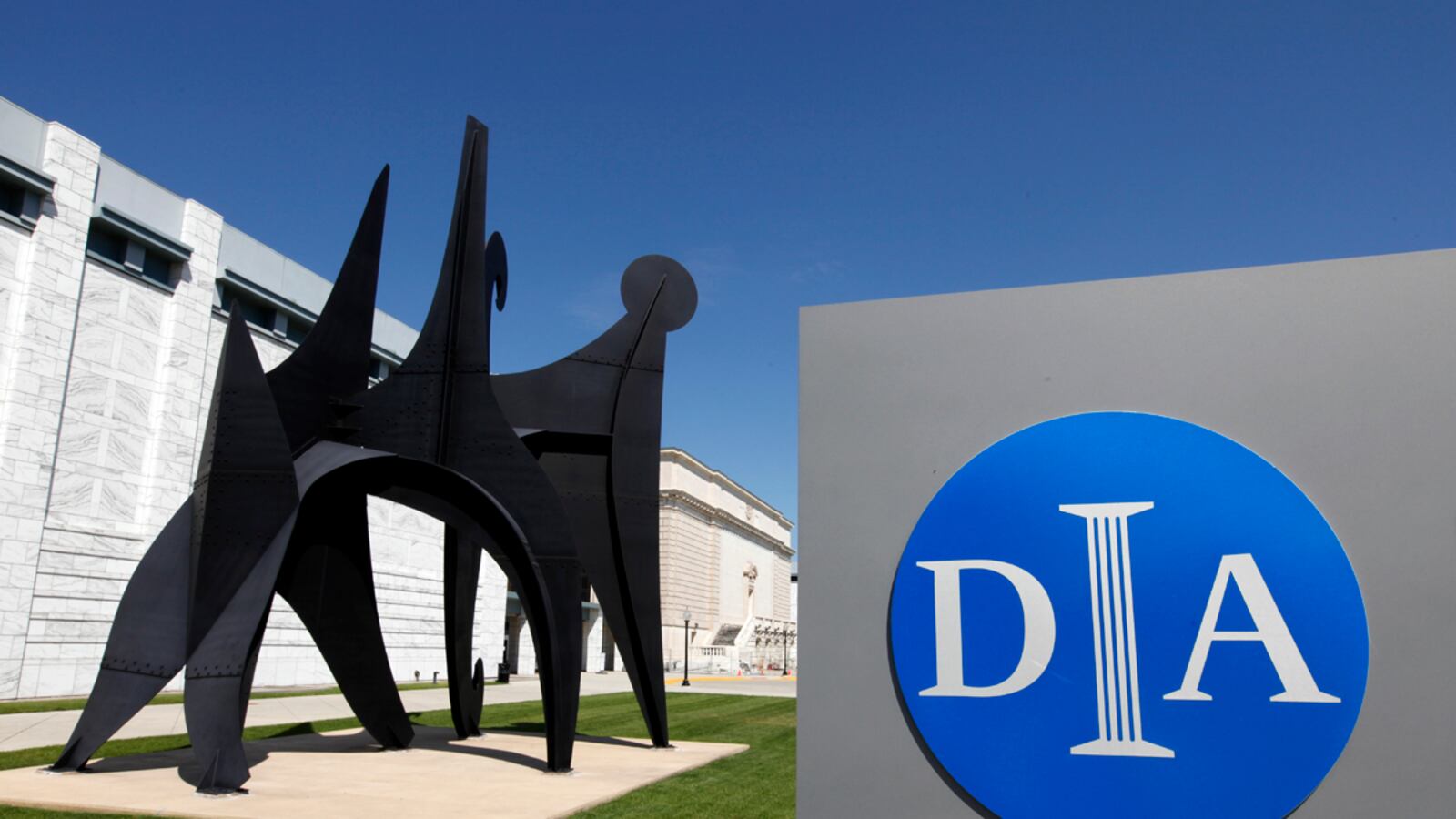

Last Tuesday, voters in three Michigan suburbs agreed to a raise their property taxes to save the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), which has struggled mightily with its finances for the past decade. Unlike most major metropolitan museums, the DIA operates without a significant endowment and receives no financial support from the city of Detroit or the state of Michigan.

Voters approved what’s known as a millage tax, a fee assessed on the value of your home. The more your property is worth, the higher your tax. In this case, the DIA levy costs approximately $15 for every $150,000 of a home’s fair market value, and will raise around $23 million a year from Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties (the last of which includes Detroit).

According to the DIA, residents of these three counties make up 79 percent of the art institute’s 400,000 annual visitors. The museum plans to use the new funds to cover basic operating expenses, not to increase its endowment—and it’s giving free, unlimited admission to residents of the counties who approved the tax. And since the election, The Detroit Press reports, attendance has more than tripled.

As of last week, the DIA now joins a handful of museums, including the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the St. Louis Museum, which rely on property taxes to make ends meet on their everyday operation costs. In fact, voters in the same three Michigan counties approved a similar tax hike to fund the Detroit Zoo in 2008 and the suburban SMART bus system in 2010.

But Richard Pomp, a law professor at the University of Connecticut and an expert on state and local taxation, warns that the average hard-pressed voter may not always choose to fund public goods such as art museums. In today’s world, taxpayers may ask themselves whether they really need to support a brick and mortar museum, when more and more of the world’s best art collections are available for a virtual tour online, through programs like Google Art Project.

“During more affluent times, we could afford to bury this kind of conflict,” Pomp explains. “On the other hand, in an era of diminishing resources, there’s an aspect of culture war going on here that can’t be denied. People will ask themselves, what good is it to go look at paintings? We know people are voting to fund public goods like libraries and bike paths, but are millage overrides going to be the new paradigm?”

The Detroit museum was keenly aware that asking people to pay more taxes to fund art might not be well received in some circles, and that the millage vote placed the reasons for having an art museum in the first place front and center.

“There’s a significant anti-tax movement here in Michigan,” says Annmarie Erickson, executive vice president and chief operating officer of the Detroit Institute of Arts. “And they took the position that, as we’re only now emerging into an economic recovery, any tax increase should pay for other, more important services—not art.”

Getting ahead of critics, the museum hired a professional campaign team and mobilized every resource at its disposal to run what was, in effect, a political campaign to ensure that the museum stayed open. According to Erickson, in the weeks before the election, the museum’s 700 volunteers as well as the DIA’s auxiliary groups worked the phone banks, reaching out to voters in all three counties. And last Tuesday, museum employees stood outside the polls, making sure art was the first thing on every voter’s mind as they walked into that voting booth.

“We’re certainly sympathetic to people who don’t want to pay more taxes,” Erickson explains. “We don’t like to talk about it. But taxes are the price we pay for a civil society.”

In this economic climate, art museums everywhere know just how hard it is to show the communities they serve how indispensible they are.

For instance, while the Birmingham Museum of Art receives half of its operating budget from the city, the museum is all too aware that these municipal funds are not an indefinite promise.

“We followed the vote in Detroit very closely,” says Jeannine O’Grody, the museum’s deputy director and chief curator. “Every day, we look for new ways to share [the museum] with the community and become more meaningful to Jefferson County and the surrounding areas. For example, we have dedicated programs in our city schools that are part of the curriculum … We pay for the buses, and we develop the materials.”

But letting the public decide which art museums to fund through tax revenue may not be as problematic as it first seems. After all, a taxpayer’s elected representatives make the same decisions in their appropriations measures each year. And the income tax encourages taxpayers to make charitable contributions to the nonprofits of their choice and take an offsetting deduction on their tax returns.

As Jill Manny, a professor at the New York University School of Law, points out, “The charitable contribution deduction is, in effect, a matching grant from the federal government to charities selected by taxpayers.” For example, if a person with a marginal tax rate of 35 percent contributes $100 to the DIA this year, the contribution costs the taxpayer only $65, while the remaining $35 is effectively paid by the federal government.

So it turns out, Detroit’s new millage tax isn’t so far outside the box. Essentially, three counties have made a communal decision to make a charitable contribution in the form of higher property taxes, which are also deductible. In fact, Michigan might just be on to something—and we may have just glimpsed the future for America’s art museums.