Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me. By Harvey Pekar and J.T. Waldman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2012. 176 pp.

Last month, The Economist published a special report, Judaism and Jews: Alive and Well. Its author, a former Haaretz editor, drew out the dissonance between the Orthodox hierarchy in Israel and postmodernity of the diaspora. “Exactly what defines Jewishness remains a matter of much debate,” he wrote. That debate isn’t always welcome, especially when it comes to the role of Israel among the diaspora.

The new graphic novel Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me is a meditation on that theme. Harvey Pekar and illustrator J.T. Waldman emphasize the authenticity of the American Jewish experience and logic of anti-Zionism by riffing on Pekar’s conservative upbringing in 1940’s Cleveland. The trouble is, Pekar has never set foot in Israel or Palestine. Nor does he include a single Israeli or Palestinian voice in his chronicle of Israel’s founding and Palestine’s Nakba (catastrophe). And so the critique smacks of the same tribal hypocrisy he abhors.

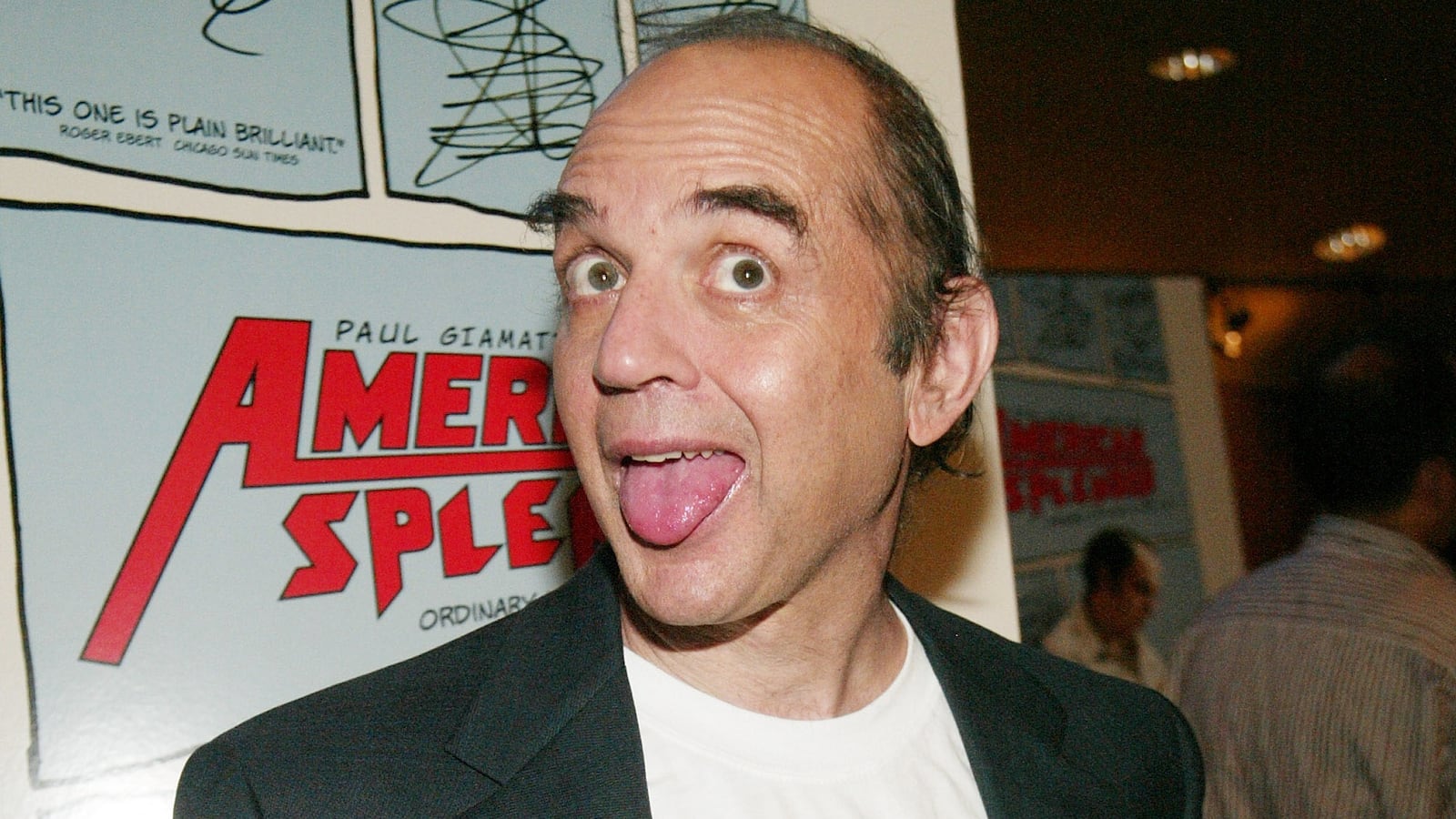

In life and in writing, Pekar’s attitude was self-effacing and sardonic, which propelled him to the forefront of the then emerging underground comic scene. This, his final book, went to press two years after his death. So in some ways Pekar is more of the book’s subject than its writer; banter between Pekar and Waldman drives the narrative. Yet despite his vast knowledge of Israel’s successes and excesses, the story of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory is told from afar. The story relies on interspersed historical glosses, with illustrations that add little (from pastiches of ancient history to composite characters, like a Tel Aviv urbanite saying, “These Orthodox fanatics want too much.”). Such a broad sketch of three millennia is by nature sloppy. And it clashes with Pekar’s overarching message. He says that he just wants “people to wrap their heads around what’s going on there today.” But where are the voices from today?

The graphic novel can be read as part of a new literature of proud Jews who are embarrassed by Israel’s position as eternal occupier of Palestinian and Arab lands. Readers of “Open Zion” know Peter Beinart’s thesis that non-Orthodox American Jewish youth are less connected to Israel than their parents and grandparents. Pekar seems to offer himself as a case in point. But his lament, that “Jews make awkward colonial overlords,” is not surprising—it’s part of a developing genre.

What separates this book is that an anti-Zionist perspective is driven home, albeit as Pekar and Waldman cruise around Cleveland and deliberate over where to eat lunch. The authors disparage the blind faith among American Jews toward Zionism, but then aren’t exactly sure how to develop the story arc of their comic. (One telling moment is when Waldman asks, “Harvey, what are we going to do with the middle of the story?” Pekar answers, “Oh, I don’t know. I’m just tired of people saying I’m a self-hating Jew because I’m critical of Israel.”)

Daniel Gordis, an American-Israeli columnist whose writing is a bellwether of Israel advocacy groups, would take issue with Pekar’s perspective. Recently he wrote, “The end of Israel would, in short, end the Jewish people as we know it.” In contrast, Pekar’s criticism of the Zionist project recalls “diasporism,” a philosophy detailed in Philip Roth’s 1993 novel, Operation Shylock. In the self-referential narrative, Roth grapples with his doppelgänger, a false prophet who asserts the centrality of diaspora to Jewish life. The lookalike prods him:

What happens when American Jews discover that they have been duped, that they have constructed an allegiance to Israel on the basis of irrational guilt, of vengeful fantasies, above all, above all, based on the most naive delusions about the moral identity of this state?

Pekar parallels this, notably in axioms like, “Nationalism and ethnic pride… delay human development.” And he repeatedly questions why Israelis would settle in the West Bank and Gaza (“This is a really stupid thing to do!”). Like Roth, he feigns surprise that the Jewish mainstream has shut out anti-Zionist perspectives.

There is a canon of comic literature on Israel/Palestine that acutely captures the conflict as journalistically as any broadsheet. For instance, in Footnotes in Gaza, Joe Sacco vividly illustrates daily life in the occupied territory. Palestinian cartoonist Naji Al-Ali has covered similar ground through the character Handala, a young boy who witnesses the tragedies facing Palestinians. Likewise Eli Valley interrogates the limits of free speech within the American Jewish community in the weekly Forward. His work is more effective than Pekar’s because he can laugh out loud at the contradictions of Jewish tribalism. Pekar, on the other hand, inadvertently validates such boundaries since, from the vantage point of his hometown, he suggests that the only way to overcome the prevailing sentiment toward Israel is to kvetch about it.