What has eight legs and just might have a soul?

The answer, surprisingly, is an octopus.

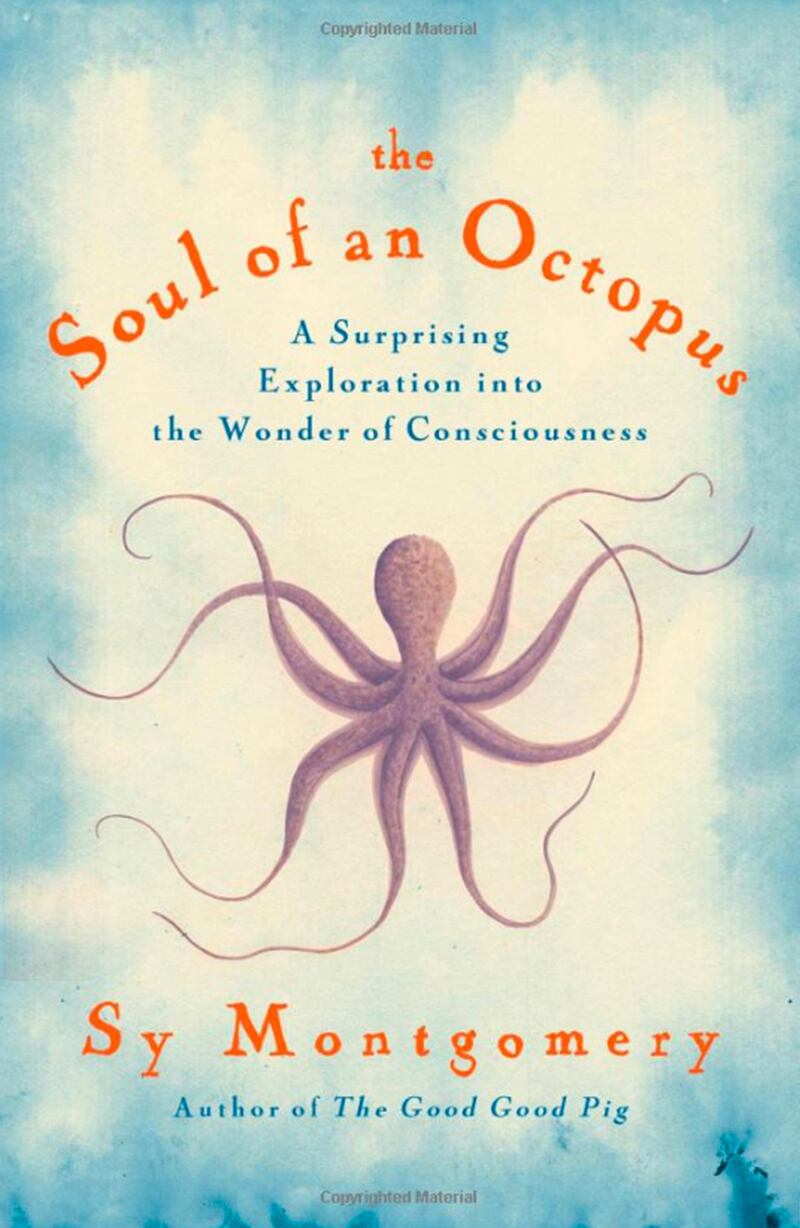

These leggy cephalopods, long a prominent player in human fear of the ocean depths, are the subject of a touching yet informative new book by Sy Montgomery, The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness.

In her attempts to understand the octopus, a creature that for a variety of reasons has caught her eye, Montgomery, author of The Good Good Pig, befriends the men and women of the New England Aquarium, and while there she develops what can only be called a relationship with its various octopus inhabitants. The book is sort of three in one. It is in part an attempt to grapple with animal consciousness as it relates to the octopus. It is part grab-bag of interesting factoids about this incredible species. And it is also a memoir, as Montgomery is very much a part of the story—it follows her relations with fellow enthusiasts, her struggles with scuba diving, and her own emotional connection to the creatures.

“The commonest of sea creatures are miracles,” writes Montgomery, and the octopus is a prime example.

Octopuses (not octopi) are fascinating enough to fill a whole book. Most of the book focuses on the giant Pacific octopus. One of these creatures can have 1,600 suckers, each of which can lift 30 pounds. Each individual sucker can work like our finger and opposable thumb, allowing it to pinch and grab things. They can taste with their entire bodies, but their suckers are especially powerful and attuned to chemicals. Their blood is actually blue, as it uses copper to carry oxygen, whereas we use iron. It also has three hearts and is literally mind-bending as its brain is found around its throat.

We may imagine that the octopus feeding itself tentacle to mouth, but as Montgomery points out, it actually runs its food along its suckers like a conveyer belt so as to enjoy and taste it. They can regrow limbs that are just as good as the one that was lost. They also sometimes mate at a distance because they might kill one another.

They are also incredibly slippery, and not just because they are covered in slime. One of the foremost problems with keeping octopuses in captivity is that they are excellent at escaping, and through holes that are tiny fractions of their regular size. “Any hole, they’re going right through it,” one expert tells Montgomery.

The more difficult part of the book for the author is trying to grapple with the level of “consciousness” octopuses have—do they feel? Think? Love? Experience complex emotions? Have free will?

While Montgomery admits she comes up short in this department, largely due to the lack of existing science, what she does manage to write about convincingly is the degree to which octopuses are far more complex and intelligent than I ever fathomed.

Octopuses are invertebrates, creatures generally considered on the dumber side. And yet workers at aquariums across the country find themselves constantly coming up with ways to entertain octopuses. One aquarium has given its octopus tools for it to paint. Another gave its octopus a ball to play with, only to find the octopus unscrewing and screwing it back together.

They are one of a select number of species that can follow a human pointing at something. Octopuses also can adopt anywhere from 30 to 50 patterns that allow it to camouflage itself, and can do so “in seven tenths of a second.” Oh, and they somehow manage to do this while being colorblind. One at the Seattle Aquarium famously picked off dogfish sharks in its tanks.

While that certainly makes the octopus interesting, and certainly much more complex than a clam, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a self-aware being. If one even accepts that free will exists for human beings, how does one measure it for an animal?

One way Montgomery looks to is something called theory of mind, or the “ability to ascribe thoughts to others, thoughts that might differ from our own.” She argues that the octopus succeeds at this test because in order to hide from predators, and to hunt its prey, it must command an astonishing array of methods that require understanding the motives of other creatures. “Of all the creatures on the planet who imagine what is in another creature’s mind, the one that must do so best might well be the octopus,” writes Montgomery, “because without this ability, the octopus could not perpetrate its many self-preserving deceptions.”

Prominent scientists, including Stephen Hawking, signed a statement in 2012 claiming “humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness” and included octopuses on this list.

Yet with octopuses this is especially tough, as so much of their “self” is spread out across its body, such as the neurons in its arms. As one philosopher who also is an expert diver, Peter Godfrey-Smith, posits to Montgomery, thinking about the octopus in terms of consciousness could mean using different criteria. Instead of a central consciousness, could it have a “collaborative, cooperative, but distributed mind” or even multiple “selves”?

The third component of the book, the memoir part, is actually incredibly sad. Octopuses live very short lives of only a few years. Montgomery finds herself building up a close attachment to these wonderful creatures, only to suffer heartbreak after heartbreak. But this personal aspect means that after reading the book, you will likely think the unthinkable and want to experience an octopus latching on to your arms and tasting you. But the creatures also die in a very tragic way. They become senescent, and act similar to a human with Alzheimer’s in that they seem lost at times, as if their mind is somewhere else.

The animal-consciousness debate is far from over, but its impact on subjects ranging from what we eat to conservation efforts is hard to overstate. What informative but entertaining books like The Soul of an Octopus do in the meantime is remind us of just how much we not only have to learn from fellow creatures, but that they can have a positive impact on our lives.