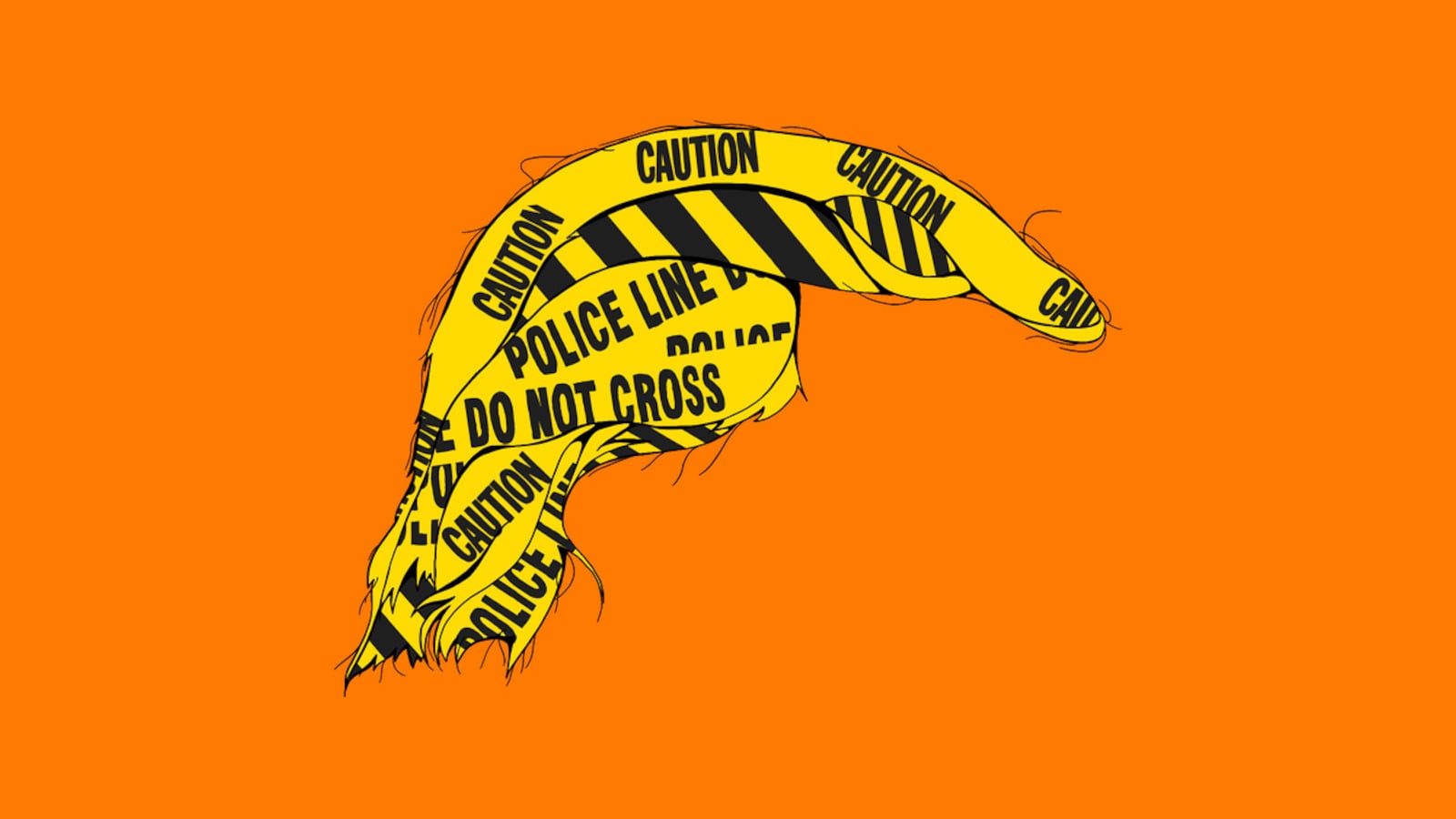

As Donald Trump’s Secret Service detail—and the size of his MAGA rallies—has ebbed and flowed, one standard operating procedure for the former president has remained constant: Whenever possible, stiff the contractors.

For all the “back the blue” merchandise one can buy at a Trump rally, finding an event where the cops actually working it had their overtime covered by the campaign is surprisingly difficult. But there’s a cost for Trump, too; the hefty bill that he tends to leave with local governments means the ex-president may have to search for even smaller, more obscure rally venues for his 2024 campaign.

In Sioux City, Iowa, for example, the former president owed more than $11,000 in unpaid reimbursements to the city police and fire departments from a rally he held there on Nov. 3, 2022. While overtime pay to cops and firemen totaled more than $10,000 on the overall tab, Trump’s Save America PAC also rented several parking lots from the city. After pressure from city officials and the local paper, the Sioux City Journal, they eventually paid up.

In Warren, Michigan, however, a city official—who requested her name be withheld—told The Daily Beast the city has yet to see any repayment from Trump for the overtime pay that cops racked up from a MAGA rally held on Oct. 1, 2022, at the Macomb Sports and Expo Center, a 2,800-seat dual arena and convention center.

In Lorain County, Ohio, Trump was joined at the county fairgrounds by Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and Jim Jordan (R-OH) for a rally in June 2021. On Tuesday, local police told The Daily Beast they couldn’t find any reimbursements for any Trump rallies.

Of the 30 counties and municipalities The Daily Beast contacted to ask whether they’d been reimbursed for local cops and firemen supporting a Trump rally, just one—the city of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania—responded to confirm they got any money back.

But an official at the city clerk’s office wasn’t even sure it was Trump’s money.

“I don’t write the name, I only wrote the check number,” said the official, who also requested her full name be withheld. She said it was unclear if Event Strategies—the main vendor for Trump rallies along with Save America—had paid for the reimbursement, or if it came from elsewhere.

The Trump campaign did not return The Daily Beast’s request for comment.

The evolution of MAGA events over the years is, in part, a story of the consequences of Trump’s pattern of leaving behind the tab. His 2016 insurgent bid was defined by the raucous crowds that gathered in packed arenas and stadiums across cities big and small, even as he reportedly began to burn bridges with law enforcement agencies over unpaid bills.

By the end of his presidential term in 2021, Trump still owed more than $2 million in overtime reimbursement and other expenses, according to an Insider and CTV News analysis.

The ex-president’s most recent venues have mostly been at fairgrounds and airports far from city centers. Officials have previously spoken to the connection between Trump’s indifference toward paying his bills and the quality of his rally venues.

In 2019, Richard Myers, a Colorado cop and the executive director of the Major Cities Chiefs Association, explained why police departments wouldn’t be thrilled to have a Trump rally come to a major downtown arena.

“When one considers how much money campaigns raise and spend, it does not seem unreasonable to expect some degree of reimbursement for such demands for service,” Myers told the Center for Public Integrity.

But as Trump’s 2024 bid gets off to a listless and low-energy start, there’s a deeper issue for the ex-president and his team if they hope to recreate the MAGA rally magic of his 2016 and 2020 runs.

The WWE-meets-megachurch manifestation of the former president’s political appeal isn’t dead yet, but the demand isn’t what it once was and may not come back for a while, one of his former top advisers told The Daily Beast.

“The reality is that if Donald Trump wanted to throw a huge rally, he might not get 20,000 people to show up,” Alyssa Farah Griffin, Trump’s former White House communications director, said. “Closer to primary season, that’s very possible, but he’s the weakest he’s ever been.”

Indeed, it’s been over 100 days since the last full-fledged open-air Trump rally, a frigid made-you-look routine at the expense of future Sen. J.D. Vance on a tarmac outside of Dayton, Ohio, where he prematurely teased his third presidential bid.

Since then, Trump has embarked on an uncharacteristic foray into retail politics, taking a watered-down version of the MAGA rally to closed-door events aimed at shoring up support among party brass in early primary states. In a visit to the disaster-stricken town of East Palestine, Ohio, last week, Trump played president again, touring the area with Vance and handing out McDonald’s to star-struck residents.

One recent rally indicative of Trump’s changed dynamic came on a rainy May 2022 night in Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

Although Trump had previously held events at the Pittsburgh airport and its downtown convention center, the Greensburg rally for failed Senate candidate and recovering TV star Mehmet Oz—who was repeatedly booed by attendees—fell about an hour outside the city center and relied heavily on a standing-room-only section. The two biggest seating areas protected from the rain along the grandstand were covered in a pair of oversized American flags, an apparent attempt to hedge off any empty crowd photos during the storm.

At the standard post-presidential Trump rally, around a dozen Secret Service officers operate the line where attendees and VIP guests go through a set of metal detectors. Beyond the first security line, the bulk of first responders in the given venue are local cops; county sheriffs and state police are also usually on the scene, along with emergency first responders with a fire department.

According to Farah Griffin, the first signs of shaky demand for Trump’s rallies emerged at the infamous debacle in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in June 2020. With the arena not even two-thirds full by the time doors closed, Farah Griffin recalled thinking for the first time Trump could lose re-election.

She noted that attendance bounced back when he traveled later in the pandemic, but the salad days were clearly done.

“We realized some of—let’s call it ‘the magic’—might be starting to die,” she said.

Another GOP strategist, who requested anonymity to speak candidly, said Trump’s far-flung events have underscored his core political problem. “You’ve gotta be appealing to somebody other than your base,” they said, “and people are tired of it.”

“It shows his limited range,” the strategist added. “I don’t think he’s in as much demand as he thinks he is.”

Trump’s 2020 operation always struggled to find a way to translate rally attendance into veritable voter turnout boosts, Farah Griffin said, though she added their political impacts are “hard to quantify.”

The sag in demand for MAGA rallies began to reach a critical level in the home stretch of the 2022 midterm season. When Trump traveled around the country to stump for GOP allies running in congressional and statewide elections, he was met with smaller crowds and stranger destinations.

The venues included a field on the side of I-95 an hour outside Raleigh, to the Richard M. Borchard Regional Fairgrounds in Texas—some two hours south of San Antonio and over three hours west of Houston—or any one of the other nine state, county, or regional fairgrounds Trump swung by over the past two years.

But Farah Griffin cautioned that it would be unwise to write Trump off based on his increasingly far-flung and less-attended events.

“I think Trump is the most diminished he’s ever been,” she said, “but I still tell people to never sleep on Donald Trump.”