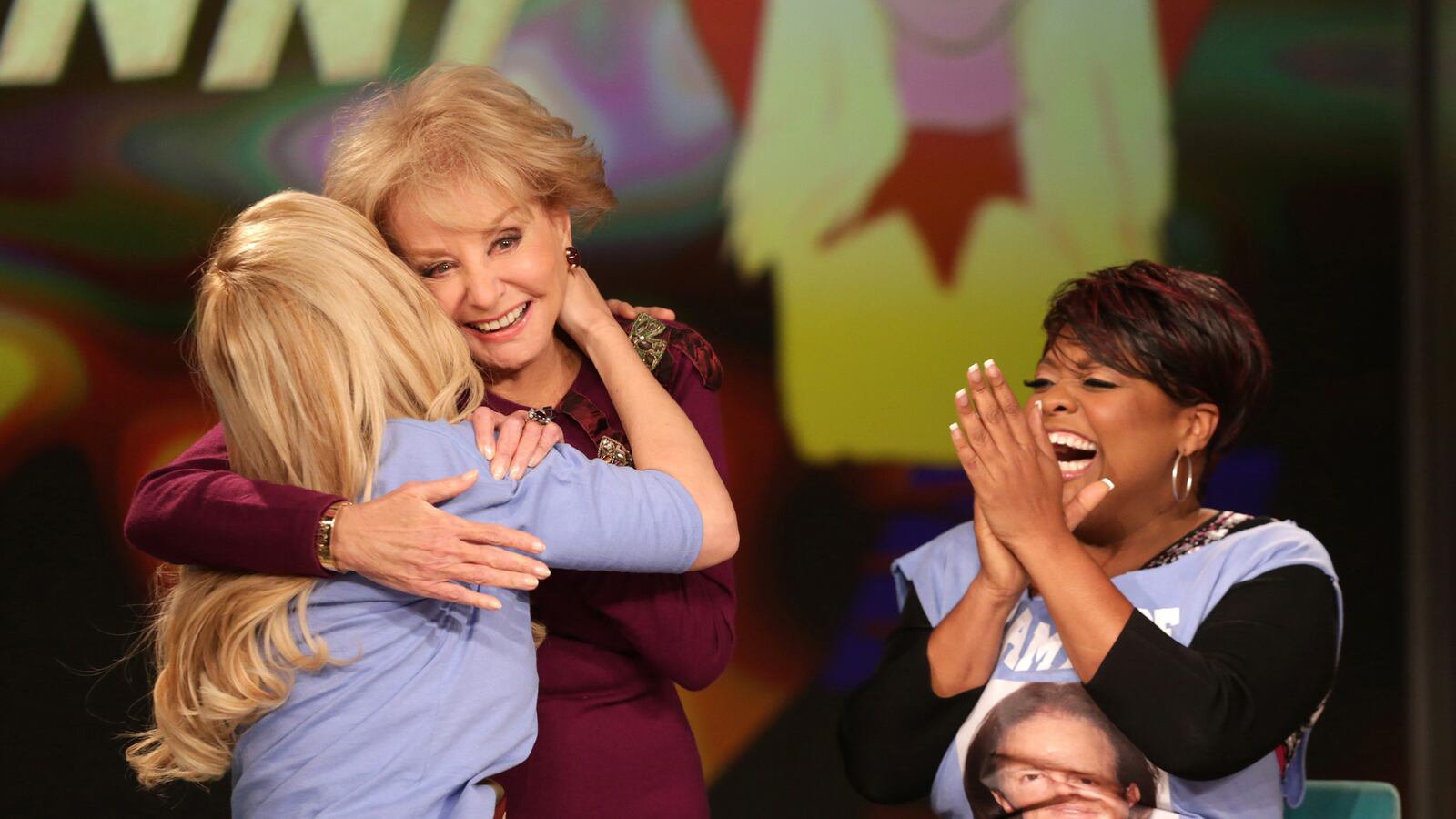

The audience was still cheering reverently for Barbara Walters on Tuesday’s edition of The View, the day after her announcement that May 16 would mark her final day presenting the ABC morning show. Her hair its usual whipped and spun golden halo, Walters came out of the wings, gingerly high-fived some folk in the audience, before her fellow host Whoopi Goldberg reminded us of her momentous imminent farewell again and—because this is all about product, ultimately—that Walters was the cover star of this week’s Variety magazine.

The magazine’s cover dutifully flashed up: Walters is shot starkly in profile, with the headline: “Her View.” The emphasis in the piece is that Walters is leaving our screens on her terms. She liked the profile shot, Walters mused; before she had always thought she should get a nose job.

It’s these nuggets of personal information, both the audience and tabloids lap up of The View. But it is also a forum in which Walters plays on, and plays up to, her own regalness. “I want to make this very clear. I’m leaving, she ain’t,” Walters, said pointing at Goldberg, during a segment about the succession rumors around David Letterman. There will be a week of View-centerd events around Walters’s departure, and a two-hour special. American television knows how to lionize its departing monarchs: Walters’ will be known as “ABC,” “A Barbara Celebration.”

All of this is merited: Walters, 84, became the first female co-anchor of any network news program with Today in 1974; two years later she became the first female co-anchor of a network evening news program on ABC. From 1979 to 2004 she co-hosted and produced 20/20, and created The View in 1997. The format of women sitting around a table hardly seems revolutionary now, as copied and hackneyed as the format has become (most shamelessly by CBS’s The Talk).

Walters is a seasoned ratings-chaser, and a politic one. She doesn’t waste her access; she says, like all of us who interview others for a living, that the worst thing would be to leave an assignment, thinking, “coulda shoulda woulda” about questions left unasked. Some of her questions have entered media folklore, asking Katharine Hepburn if she was a tree, and Monica Lewinsky if Bill Clinton was a “sensuous, passionate man.”

She interviewed Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat and Israel PM Menachem Begin in the late 1970s, and later Vladimir Putin, and the Obamas.

Years after she did them, Walters talked about what sounds a golden era of interviewing and film-making; of taking Henry Kissinger back to his hometown, where the players in a football match stopped to honor him; of riding alongside Fidel Castro in his car in 1983, him driving her into the mountains, blowing cigar smoke in her face.

In 2008, she interviewed Castro again, in which the Cuban leader flirtatiously told her she doesn’t look as if 25 years have passed since they last met. He tells her he is flattering her so she doesn’t ask him tough questions. She asks why he is wearing a suit, rather than military garb. “Precisely to seduce you…so you are kind to me,” says Castro.

In 1988, Walters interviewed Mike Tyson and his then-wife Robin Givens, eliciting Givens’s revelation that Tyson physically abused her. “He shakes, he pushes, he swings,” Givens said. ”Just recently I have become afraid. I mean very, very much afraid.”

The View, like its creator, was a trailblazer, which sadly over the years has mutated from a spirited round-table discussion to a shrill, on some days utterly off-kilter, mess. Ironically, the show that Walters has as her goodbye vehicle ill-serves her and her reputation. Its original distinctiveness is something to proud of, but not its current incarnation.

On Monday, Walters, announcing her departure date to a standing ovation led by Goldberg, predicted many happy future years of watching Bill Geddie, her fellow executive producer who lurks off stage, get older and balder, as she got blonder.

To the casual viewer Walters’s attitude seems split. She is a doyenne, she commands immense respect, yet she bats away the gloopy public adoration foisted upon her, and that does not seem like an act.

One senses she likes a fuss to be made of her, but the right kind of fuss. In the Variety article, it is revealed she still phones celebrity handlers to secure interviews: the pulse of Walters is still that of a jobbing journalist, regardless of the scale of her entourage and her grandeur. Whatever form her retirement takes, Walters does not rule out breaking it if an interview with, say Fidel Castro, if it presents itself. She still wants to be in on the scoop. There may be a male co-host for The View, she intimated. “Don’t cry for me Argentina,” she added, lest we all lapse into a Walters-style sobfest at her imminent departure.

For anyone younger watching her on this strange, high-pitched daily basis, The View should not be what she is remembered for. The show now desperately chases shorter and shorter tabloid returns: after Walters had made her announcement on Monday, the women discussed as a “hot topic” the marriage of Kandi Burruss, a cast member of the Real Housewives of Atlanta, and the interfering spectre of Burruss’s mother Mama Joyce.

Even the show she does every year, rounding up that year’s top “most fascinating,” people is now overwhelmingly the Kardashian end of the market. But she does this with as little eye-rolling as possible. On The View, she has spiritedly defended her friend Woody Allen, and joked about having a vibrator called Selfie.

The “hot topics” segment of The View—an editorially chaotic mix of showbiz stories and the kinds of stories (mother leaves child in a car, Fox News doctor calls for an end to anonymous sperm donors)—the producers hope will echo with their imagined heartland housewife audience. The departure of the leftish Joy Behar and the right-wing Elisabeth Hasselbeck has robbed the show of an innate political and cultural animus.

Were it not for Goldberg, the panel after Walters’s departure would fall far short of appointment viewing. Its recurring phrase is now the deadening, argument-stifling “As a mom,” cited frequently by Jenny McCarthy and Sherri Shepherd. The primacy of motherhood, as experience, as the great qualification to hold an opinion about anything or justify any action, is ploughed relentlessly. On The View, if you are not a mother, or if you seek to justify your opinions without recourse to your experience of parenting or “being a mom,” you are toast.

The View’s most defining flashpoints have been its rows, most famously between Rosie O’Donnell and Hasselbeck over Iraq, which led to O’Donnell leaving the show. After that incident, Walters put on her most honeyed tone to steady the ship: she is both diva and mother hen, and imperious and firm in either register.

On Tuesday’s show, consensus was quickly reached over leaving your children in a hot car (bad, although the woman concerned was at a job interview), and Vogue selling 400,000 copies of its “Kimye” issue (good, why were people so worked up about it in the first place). The emphasis, even on Queen Barbara, is to be as personal as possible, and so it was—when discussing anonymous sperm donors—that she claimed she would not be in favor of banning them.

Walters has a now-adult adopted daughter, Jackie, who she said didn’t want to know who her real father was, but did want to know his medical history: that should be made available with anonymous sperm donors, nothing else, Walters said, and nothing should be banned. Despite her she-who-must-be-obeyed air, sometimes the women break ranks, as when Shepherd signaled her strong upset over Walters using the n-word. The debates between the co-hosts, and interviews with guests, descend into chaotic babble-fests, which must be good for ratings and buzz presumably.

Goldberg and Behar walked off when offended by Bill O’Reilly, and in her visits Ann Coulter induced similar outrage.

In 2008, Walters imperiously asked Tina Fey, one of her “fascinating people” that year, what was it about The View that had made Fey satirize it, as a then-Saturday Night Live writer, years before?

Fey, to her credit, didn’t wilt under Walters’s beady challenge, and said with a smile on her face that the first impulse had been how all the women talked over each other. Walters, jokingly, immediately began speaking over her.

Is The View now as Walters wishes it was? It falls far short of radical, its voices are far from fresh. Its topics are the predictable pop-culture bellwethers of the day, reheated into screechy mush. Only Goldberg’s vinegary unpredictability keeps the viewer on their toes. The length of the segments mean the “debates,” such as they are, are abbreviated and unsatisfying, reduced to soundbites and talking points, and bids for applause.

For all their assertions of being “real mothers,” the women on the show are TV personalities, and cosseted and supported as such, and too often speaking squarely from the mainstream, rather than standing distinctively in the left, right or any other field.

Walters, a master of the one-on-one interview, must find this daily din frustrating—well we know she does, because even in the confines of the round-table View she has carved herself a one-on-one interview slot with a newsmaker of some kind.

This slot harks back to what Walters is most celebrated and venerated for—her interviews. She, Oprah Winfrey, and Diane Sawyer are the queens of confession. If you have erred, strayed, if you have done something you regret, if you have something to reveal, if you are seeking contrition in primetime, Walters will probe you, with that squirrelly, clotted voice of hers, then offer you a padded shoulder to weep on.

Whether you think this is terrible or mesmerizing (or even both), whether you find it intrusive or bizarrely open to leaving the subject able to wriggle off the hook with a dollop of therapy-speak, the style of Walters’s interviewing style—emotion first, how do you feel, show me something of yourself?—is now the dominant mode of the TV interview. It became so distinctive that Walters was satirized pretty early for it, alongside that accent which rounds r’s into w’s, by Gilda Radnor and her Baba Wawa impersonation. A later skit on 30 Rock featured the “Walters” interviewer, played by Rachel Dratch, encourage her interviewee to “glerg.” “Glerg” is actually the perfect word for the hyperbolic tears Walters is famous for eliciting; dictionaries worldwide should include it immediately.

In that sense, perhaps The View is the absolutely appropriate Walters vehicle to say goodbye with: a daily hour of controlled, glistening-eyed auto-emote and confess. Her reputation is predicated on the grandstand confessional, and her legacy is this mutation, its radical origins obscured by the ratings-grabbing necessity to follow the tabloid titillations of that day.

Walters signals in her Variety interview that The View must change, and she’s right. It needs re-bolstered, strong voices at the table (Kathy Griffin, pretty please), or it will sink. Walters wants a right-wing panelist reinstated into the mix, to spice up the conflict around the social issues the program considers “hot.” She is keen to emphasize she is still in charge of the ship. “I’ll be watching you,” she tells her co-hosts, smiling, but she means it.

Regular watchers of The View will know that occasionally the camera flashes to Geddie, her longtime colleague and the program’s co-executive producer. He is sighted just off-stage, harried look on his face, occasionally smiling. At commercial breaks we see him pow-wow with the hosts. Can you imagine Walters, his executive-producing partner, post-May 16, lurking with him behind the cameras? Barbara Walters, offstage? Unthinkable.