One day in the late 1980s, my wife and I visited a staffer at the U.S. consulate in Jerusalem for an off-the-record conversation. The walls of his office were decorated with large maps produced, he mentioned, by the CIA. One showed the West Bank, with the border between it and Israel precisely depicted. Our careful journalistic distance from the interviewee evaporated. We shamelessly begged him for a copy, which he politely gave us.

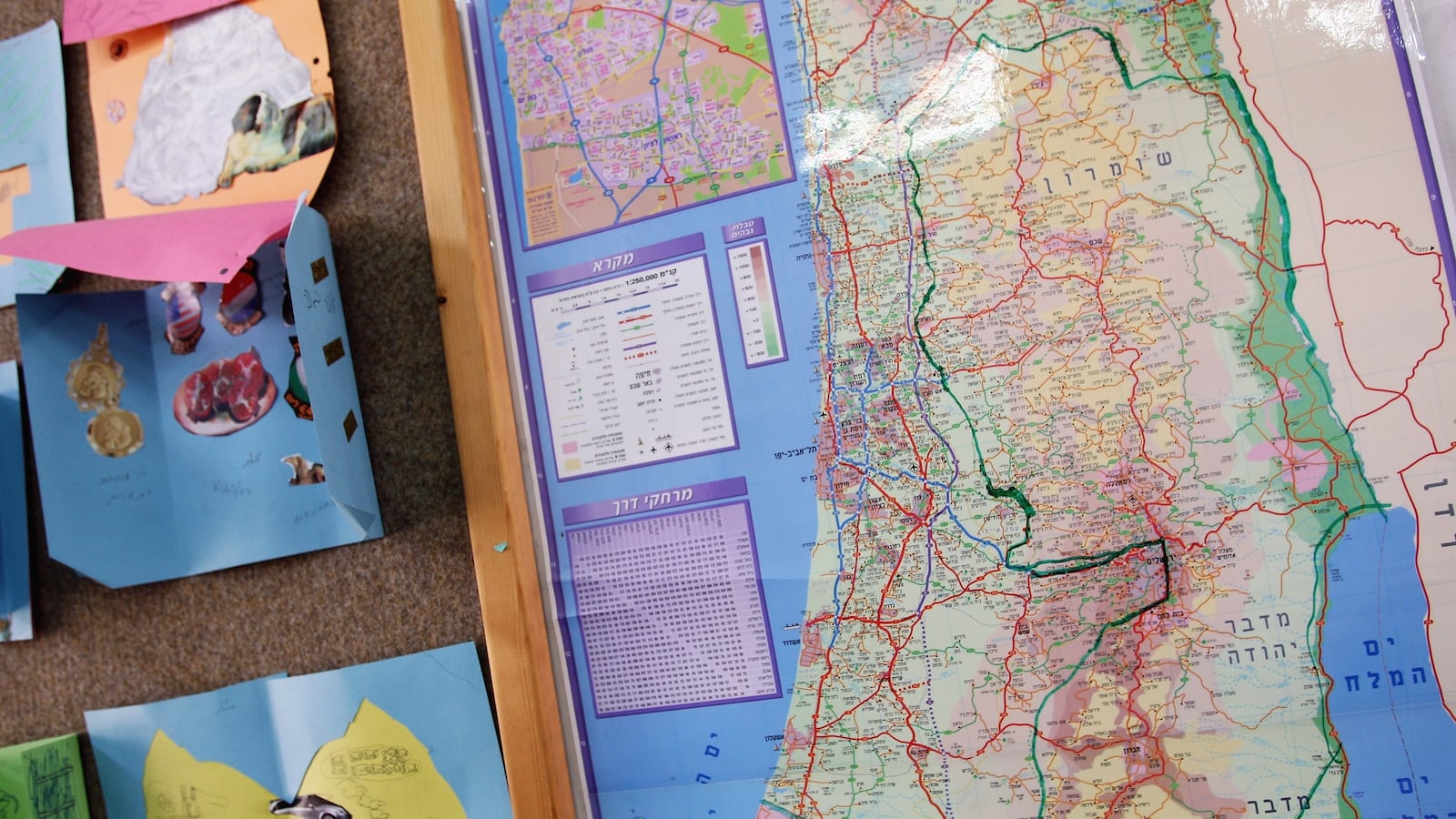

It was a treasure. In those days, the Israeli government had a near-total monopoly on mapmaking in the country—and government maps never showed the Green Line, the border between Israel and occupied territory. The Internet’s instant access to alternative maps was still in the future. To the best of my memory, so were the commercially published Israeli road atlases that today show the border in a barely noticeable gray. Even members of parliament weren’t always sure if a new community was inside Israel or was a West Bank settlement.

I point this out, firstly, to lay to rest any notion that erasing the Green Line is a recent or accelerating phenomenon. It’s not. Bibi Netanyahu did not initiate the cartographic cover-up, nor did his predecessors in the rightwing Likud. Nor was it inspired by the messianic fervor of religious activists, much as some Israelis would like to blame them for all the ills of the occupation.

To be fair, erasing the border is a game that Palestinians can play as well. A wall map that I’ve seen decorating quite a few Palestinian Authority offices shows the land from the Mediterranean to the Jordan, marked as Palestine, without any internal border.

The propagandists on each side of the conflict like to ignore their own maps and call attention to maps drawn by the other side that show a single, undivided territory. Israelis who do this say Palestinian maps deny Israel’s existence as a state. And yet, when carefully considered, Israeli maps without the Green Line do the same thing: They erase the State of Israel.

For years I wondered exactly when and how the Green Line was removed from Israel’s official maps. Then, in an Israeli archive, I came across a carbon copy of the original directive. It was written by Yigal Allon, then the minister of labor, on October 30, 1967, less than five months after Israel conquered the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the Six-Day War. Allon’s ministry included the government’s Survey Department. He told the department chief that from that day on, the pre-war boundaries should no longer be printed.

A kibbutznik and ex-general, Allon was a leader of Ahdut Ha’avodah, historically the most determinedly socialist of the parties that later merged to form Israel’s Labor Party. For Ahdut Ha’avodah, even the borders of the British Mandate for Palestine were an imperialist imposition that unjustly reduced the Jewish homeland. The borders of Israel between 1949 and 1967, created by armistice agreements, were even less acceptable to the party.

After the Six-Day War, Allon softened his hawkish views somewhat, realizing that if Israel annexed all of the West Bank and Gaza, it would turn into a binational state. His new proposal, which became known as the Allon Plan, was to keep the less populated areas and give up more populated parts of the West Bank and Gaza. Awaiting the drawing of new borders, Allon erased the old ones, with the acceptance of the government as a whole.

Allon’s action was a fiction, a self-deception. Even for internal Israeli purposes, the Green Line has remained the divider between the territory subject to Israeli sovereignty and the land under military rule. In Israeli law, the boundary was altered only by the annexation of East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. No other country has accepted those annexations, so for international purposes, the Green Line is still Israel’s border. What lies past the Green Line is under Israeli control, but it’s not part of Israel.

Since Israeli politics focus on the future of occupied territory, the Green Line remains the single most salient fact of Israeli life. It’s a bit like sex in Victorian society: crucial and repressed.

Other countries, especially the United States, have both rejected the fiction and acquiesced to it. A case in point: In 1986, Ariel Sharon was Israel’s industry minister—and was assiduously promoting construction of Israeli industrial parks in West Bank settlements. Covering that story, I asked the American embassy in Tel Aviv whether the U.S.-Israel free trade agreement applied to the products of settlements. The answer was an unequivocal no. “The occupied territories are not treated as part of Israel,” the commercial affairs counsellor told me at the time. But American officials did nothing to check whether products marked “made in Israel” really were. As the counsellor told me, “All of this is done on a lot of faith.”

The borderless map isn’t just a fiction; it’s a dangerous one. Allon thought he was creating a tabula rasa for new borders. But symbolically, he erased one of the basic elements of a modern state—a defined territory. His map shows a return to the reality of his youth, before the establishment of Israel: a single territory from river to sea, in which two ethnic groups fought for control.

Seen from one angle, the absence of the Green Line says that Israel has expanded. Seen from another, it removes Israel from the map. Seen both ways, it lends support to dogmatists, Jewish and Palestinian, determined to possess the whole land and to keep sacrificing lives until they achieve their goals.