Dominique Strauss-Kahn will not endure a criminal trial for the attempted rape alleged by a French novelist, but he could have faced charges for sexual assault had the statute of limitations not made prosecution impossible after 2006, Paris public prosecutors say. The everybody wins, everybody loses decision, the result of a three-month investigation into the alleged 2003 incident, has sparked a battle to claim the conventional wisdom before it’s too late.

Lawyers on both sides are racing to interpret the ambivalent statement, with its official suggestion that something reprehensible did happen in that empty Paris apartment in 2003, where Tristane Banon, 32, says Strauss-Kahn, 62, tried to rape her during an interview.

The former International Monetary Fund chief’s counsel declared Thursday on French television that their client had been “totally cleared” and suggested authorities had caved under media scrutiny in their assessment of sexual assault. Strauss-Kahn, they say, admitted only to trying to kiss a woman, without violence. Interpreting that as sexual assault “appears to be dictated by the circumstances, pressures, and hype,” Frédérique Baulieu, one of the lawyers, told Agence France-Presse.

Meanwhile, Banon’s attorney sounded like anything but the loser, calling the decision “a first victory,” proof Banon’s “dossier was not ‘empty’ and the facts she denounced were not ‘imaginary.’” David Koubbi told reporters his client felt “disappointment and immense joy,” while Strauss-Kahn, he said, was an “untried sexual aggressor.” Banon had already threatened to bring a civil suit if the case was dropped, and Koubbi promised more information about that in the days to come.

French counsel for Nafissatou Diallo, the Sofitel chambermaid whose civil case against Strauss-Kahn is pending in the United States, also spoke about the decision, telling French radio that the Frenchman had been “caught red-handed” in a lie and that the decision may serve Diallo’s own case.

Headlines in France on Friday focused on the assault suggestion, not the rape attempt ruled out. “Tristane Banon Affair: DSK Lied,” read the cover of France Soir, a tabloid daily. “DSK Really Did Assault Tristane Banon,” added a headline inside, above the analysis: “For Dominique Strauss-Kahn, it’s very bad news.”

On Friday, in an apparent bid to stop the bleeding, Strauss-Kahn’s lawyers released the excerpts of his statements to police that show he did not admit to any violence against Banon, only that he let go of her as soon as she refused a kiss. “I tried to take her in my arms. I tried to kiss her on the mouth. She pushed me away firmly. She said to me, in essence, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ I right away released my grip. She collected her things and left the apartment furious,” he said.

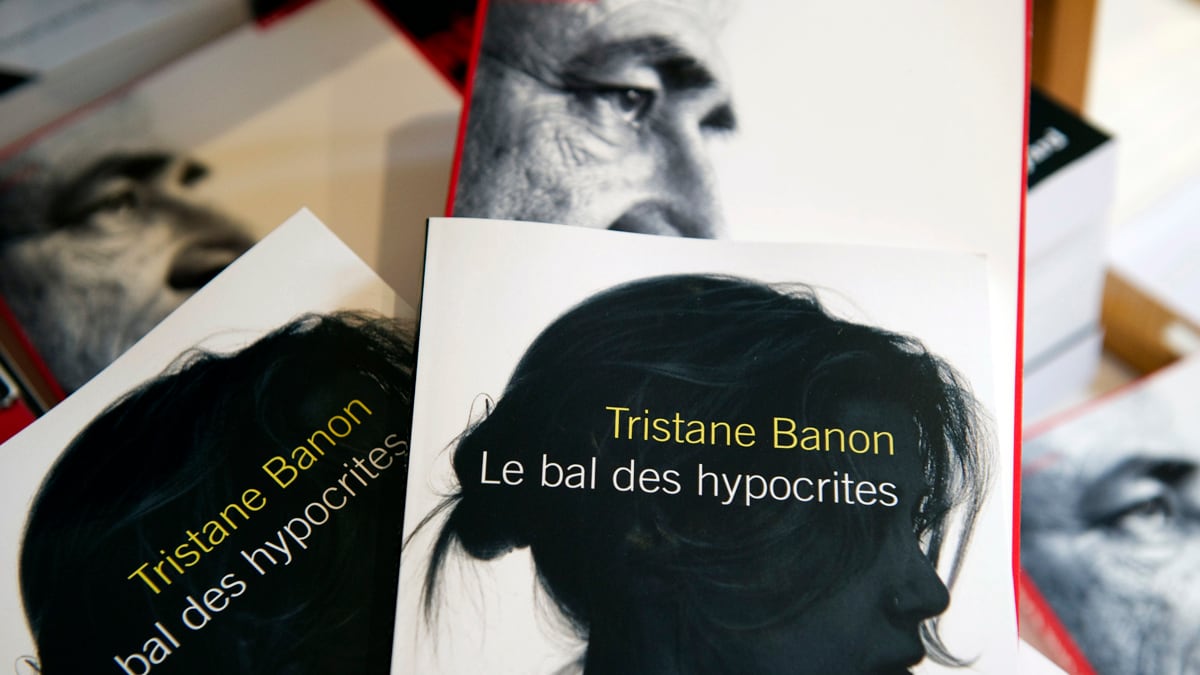

Banon’s own bid for the conventional wisdom, meanwhile, has already been launched. A novelist, she has something Diallo, the illiterate Guinean chambermaid, does not: a sharp pen. By coincidence, The Hypocrites’ Ball, Banon’s 126-page essay on the weeks leading up to her decision to take legal action in July, was released on the day the case was dropped.

The Hypocrites’ Ball will disappoint readers skimming for scoops or lurid details. The book doesn’t linger on the 2003 incident, relying on the aftermath to get the point across, and never once mentions Strauss-Kahn by name. But it is not timid, and from a writer now vindicated even as her allegation is thrown out, it will read more powerfully. “It was eight years ago and the pig stole my life,” Banon writes, referring to Strauss-Kahn throughout only with animal epithets. His wife “did not see, did not want to see the baboon behind the man. Her pig was not a full-time baboon, only intermittently ill.” She writes, “the baboon-man is my psoriasis... an illness that sticks to the skin and only wakes up when you no longer expect it.”

The book begins before Strauss-Kahn’s May 14 arrest in New York. “It is Saturday morning, 9 o’clock, and they are talking about the baboon on television,” she recounts of the morning before the Sofitel incident, when the former IMF chief’s future was still blindingly bright. “He is a superhero, messiah, savior. The specialists of anticipation say he is capable of anything: he is the one who will straighten out the country, lower taxes, understand the weak, and bring happiness and repose to every French home. Marvelous baboon.” Of the moment the story turns, Banon writes, “Dozens, hundreds of messages, my phone is overdosing, they are talking about the baboon inside it. The screen vomits his name, again and again...the baboon-man has been arrested.”

Banon’s book is tinged with doubt, though is not apologetic. She admits she wondered, like many of her compatriots, whether Strauss-Kahn was being set up at the Sofitel, so extraordinary was the news, and so close to the Socialist primaries and the presidential election. In lively prose, she recounts surreal scenes, sometimes with wry humor, and darker thoughts of suicide. She acknowledges feeling guilt over not pressing charges sooner and concedes it was cowardly to tell her story on TV before she had.

Thursday’s decision, technically a victory that means Strauss-Kahn will face no criminal charges on either side of the Atlantic, didn’t make Friday’s front pages for the most serious French dailies. They were concerned instead with Sunday’s deciding vote in the Socialist Party primary, for which Strauss-Kahn was once the overwhelming favorite.