Why is that ring seemingly suspended in air? How did those people get from there to there? To watch Antonio Díaz perform many of his illusions in El Mago Pop on Broadway (Ethel Barrymore Theatre, to Aug. 27) is thrilling in places. His magic has apparently been seen by almost 3 million people. Having already bought one theater in Spain, Díaz—the youngest illusionist to step into a Broadway theater, his Playbill says—has just bought another in Branson, Missouri, which will be his U.S. headquarters.

You may have seen a version of his most famous trick on the Today show recently, when—right in front of viewers’ eyes—he seemed to transport a group of people through thin air, from one see-through box to another. Dramatically bamboozling, it must have left thousands of spoons clattering into cereal bowls across the country.

Díaz repeats a variation of this on Broadway as a suitably gasp-worthy finale. Unless he has magically frozen time, or somehow there is an invisible screen between the audience and the stage and something fantastical happening with projections, how those people get from box to box is a mystery. He does say to the participants that if they feel something, not to move. And behind a piece of cloth we see some shaking as the supposed teleportation takes place. Whatever, it’s fabulous.

At 20, Díaz created his first company, and in 2018 he was ranked as the highest-grossing European illusionist in the world by Forbes. His Netflix show, Magic for Humans by El Majo Pop, was broadcast in 192 countries, “consolidating his internationalization” the program states.

The stage show has thrills individually. But it also, in between these tricks, a rather plodding bio-meets-advertisement for Díaz; what are clever pieces of illusion come to feel a little lost in a stage show with flaccidly interwoven bits of self-empowerment, self-hype, and blunt advertising.

In some ways it is gratifying to see an entertainer be proudly honest about what a show is really about: selling a brand, and selling stuff associated with the brand. The Broadway show is only around 80 minutes, and yet the strain of aspiring to be more than what it is—a succession of tricks—is obvious. Its pacing, construction, and tone need a lot of work to hide the joins.

The audience, via use of either being picked or the use of a ball flung, are prevailed upon for a watch, and for number choices and other mini-tasks and asks. These are the building blocks for setups of card tricks: one links together a series of answers shouted out from the audience.

Díaz’s skills as an illusionist are faultless, but the show feels off-kilter as a piece of theater. Díaz feels impressively in charge of his tricks, but not the show as a show. His audience interactions feel stilted and off. One little boy who was shepherded up on stage was lightly (not unpleasantly, but oddly) joshed with. Another amazing illusion required the participation of a female specifically, Díaz said. But, having watched the illusion (which really does have you rubbing your eyes in disbelief), this audience member was left thinking: that could have been a male. Why a female specifically?

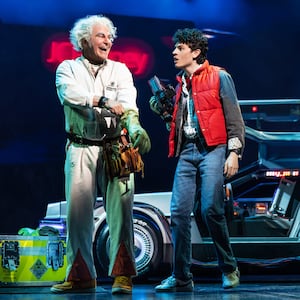

Antonio Díaz in El Mago Pop.

Emilio MadridNear the end of the show, there is a set-up where he flies across the stage and appears to walk on walls, but as we can already imagine fairly ordinary trapeze wires—as in so many stage shows—are facilitating the vision in front of us, it feels all too explicable. Segues from some set-ups to yee-gadzooks crescendos can feel uneven and swallowed up too quickly in the strange pacing of the show, rather than letting their wonder hang in the air.

In between the tricks, and to give Diaz’s team time to set up the next moment of wonder, we are given a potted journey through his life, or at least his inspiration to do what he does. This includes dramatized filmed scenes and comic strip panels of him as a little boy. These feel more like padding than revealing or profound. Around the edges of the stage we see the vibrating red vertical lines of the Netflix logo. At least for the show this critic attended, a camera crew was filming, in service of another, maybe Broadway-focused special.

As gratifyingly baffling and visually stunning as it was in places, El Mago Pop also feels very much in service of Díaz’s brand-building and product marketing, and he was being very open about that. Perhaps there is nothing wrong in this—Díaz is simply being more upfront about it than others in the fame game. But it is ironic, in a show that depends so much on sleight of hand and things we cannot explain happening right in front of us, that this most visible and obvious desire to shift product thrummed alongside the thrill of the illusions that Díaz delights in performing under the veil of concealment, mystery, and surprise. As with the best of his amazing illusions, a little less show and tell would really work wonders.