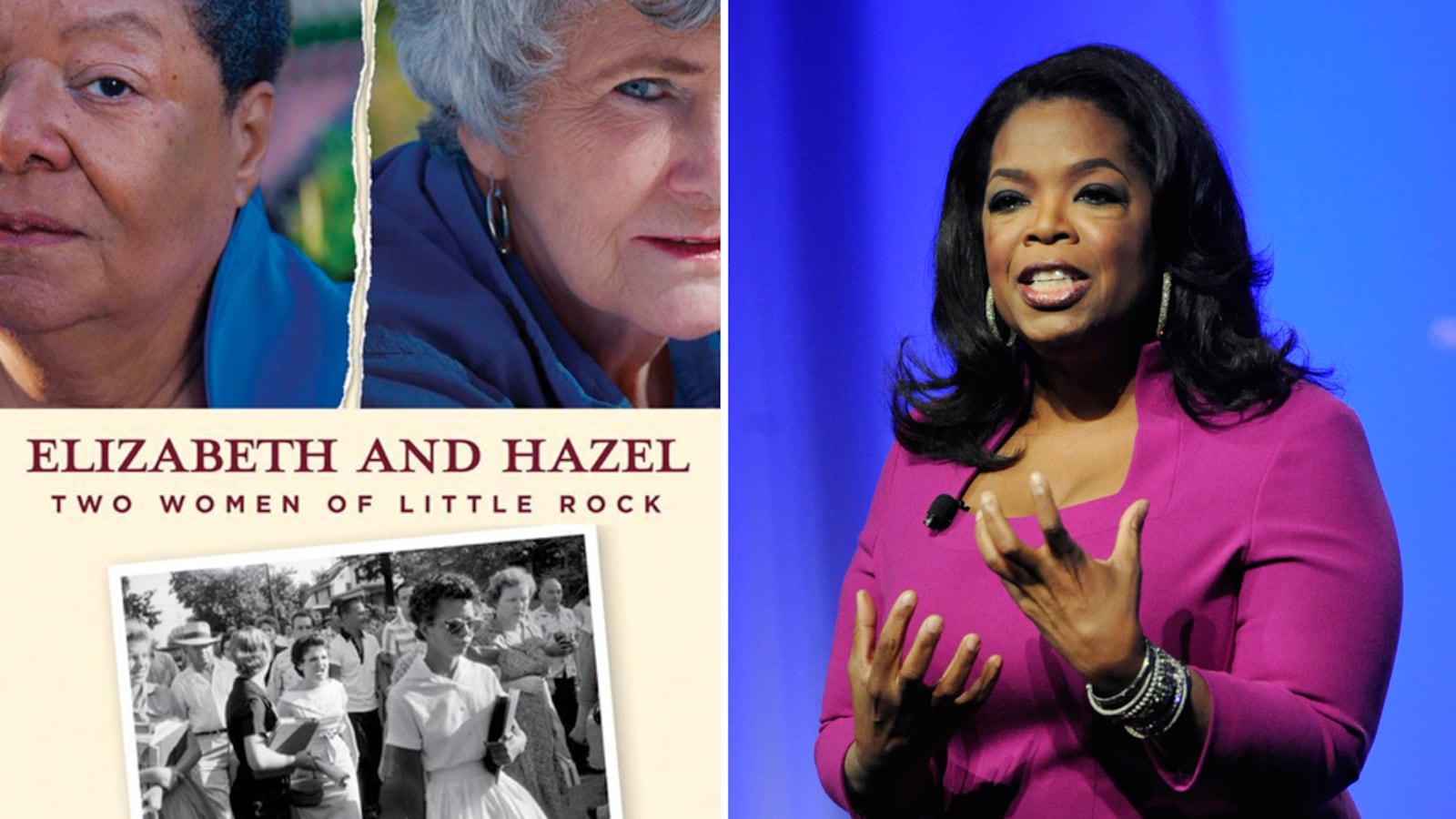

For a time, their story was the apex of Oprahism. In fact, it was hard to imagine anything more Oprahesque. But when Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan Massery appeared on Oprah in 1999, their experience was downright un-Oprahian.

Elizabeth and Hazel had first met two years earlier, on the 40th anniversary of the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. But it was hardly their first encounter. In 1957, for a fateful 60th of a second, they were both in front of Central, and linked forever by one of the most familiar, searing, and embarrassing photographs in American history.

Elizabeth was the 15-year-old black girl, dignified and stoic, being stalked by an angry mob outside the school after Arkansas National Guardsmen rebuffed her when she tried to get in. Hazel, also 15, was the white girl with the hate-filled face standing directly behind her, screaming epithets. “N***r, go home!” she’d shouted at Elizabeth, purposely trying to outdo her schoolmates walking alongside her. “Go back to Africa!” Will Counts, a young photographer for the segregationist Arkansas Democrat, had captured the moment, and the picture had flashed around the world. It was enough to get even the normally amiable Louis Armstrong indignant.

For a time, Hazel felt she had done nothing at all, and certainly nothing wrong. But a few years later, disturbed by images of black protesters being beaten and fire-hosed in the South and knowing that before long her young children would grow up to learn she was the girl in another infamous picture, Hazel had tracked down Elizabeth, called her, and apologized. The two then went their very separate ways, but Hazel continued to atone. While raising her own family, she tried to teach them tolerance, read up on black history, took underprivileged black children on field trips, and counseled unwed black mothers. To some, she grew extremely close. As for Elizabeth, she spent decades fighting the depression and despair that descended on her that first day at Central and continued through her hate-filled year there, when segregationist students incessantly tormented her and the other black students.

In the ensuing years, in which she struggled through college and the Army, Elizabeth twice attempted suicide. Eventually she was diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Though she never married, she had two sons; together, they survived (barely) on her disability checks, which would invariably be spent the first week of every month. She bought her sons’ clothes at thrift stores, several seasons and sizes in advance. She’d serve only casseroles, so that she could occasionally buy them toys. Living in a poor neighborhood, she and her boys took to carrying pieces of lead pipes in their pockets in case anyone mugged them.

Interviews, with reporters forever brandishing the famous picture or asking her to relive the day it was taken, were especially wrenching. She turned most of them down, including her first invitation from Oprah in 1996, to appear with the rest of the Little Rock Nine. In Little Rock’s black community, Elizabeth became a kind of specter, seen waiting at bus stops or walking alone, always walking alone—a living reminder that integration had come at a cost. But with the help of therapy and drugs and grit, she pulled herself out of the abyss, and in the late 1990s she went back to work: a black judge who realized she’d been poorly paid for her sacrifices hired her as a probation officer. Extremely intelligent and conscientious, she took to the work quickly, and did it well. Probationers learned she was tough: she’d pulled through, and so, she felt, should they.

Meantime, the picture kept popping up. Every schoolchild knew it, because every American history book had it. Every anniversary, every Black History month, the newspapers reprinted it. But when it re-appeared on the front page of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in September 1997, it was alongside a new and much larger picture: this one of Elizabeth and Hazel as grown women, standing—smiling—next to one another. Will Counts, who had returned to Little Rock for the ceremonies commemorating the 40th anniversary of the schools crisis, had convinced them to pose together. Hazel required little persuasion; at long last, she thought, the world could see what she had become, not just what she’d been. Elizabeth, characteristically, was more wary, but she was also curious, and she agreed.

The new picture thrilled the local movers and shakers. They seemed to believe that by coming together, these archetypal racial antagonists had magically absolved Little Rock of its sins. The photograph was promptly blown up into a poster and placed on sale at the visitor center across from Central. “Reconciliation,” it stated, or overstated. It sold briskly, especially to schoolteachers teaching tolerance.

Elizabeth and Hazel started spending time together, taking a seminar on racial tolerance, collecting awards from civil-rights groups and, though public speaking initially came hard to Elizabeth—she would have trash cans lined with Hefty bags placed alongside her, just in case she got sick—talking to schoolchildren. Along the way, something funny happened: they discovered they liked one another. For all their differences, it turned out that they shared a lot: a love of history, and thrift shops, and used paperbacks, and flowers. They were also loners, with few people, even in their own families, in whom they could confide. They discussed their lives and their children. And they began dreaming big dreams, like doing a book together. Their story, according to the proposal they had put together for publishers, was “a natural” for Oprah, addressing “the themes of triumph over adversity and redemption out of suffering that Oprah finds so compelling.”

As the millennium approached, Oprah came to them, for a program she was planning on the most famous photographs of the century. This time, Elizabeth agreed: it might help sell their book. For Hazel, it was a further shot at expiation. Tensions were already brewing between the two. The racial chasm was proving not so easily bridged: Elizabeth, ever skeptical even of those who’d tried to help her, and ever a stickler for history, found parts of Hazel’s story incomplete or unconvincing, and began treating her peremptorily. (Hazel was taking it from whites as well, particularly white contemporaries from Central who felt they’d done nothing wrong and were always having Hazel—and that confounded picture—hung around their necks.) Still, the two traveled from Little Rock to Chicago together. Joining them there were figures from other iconic images: the mother of the schoolteacher-astronaut killed on the space shuttle Challenger; the man and woman who’d embraced amid the mud of Woodstock; the crying girl, her skin burning from napalm, running naked down a Vietnamese road.

From the beginning that day, Elizabeth and Hazel felt marginalized, relegated to seats in the front row rather than on the stage with the other guests. So both felt more like bystanders than participants. Each was more of a reader than a television viewer; neither watched Oprah very often. As they followed the preparations, they were more clinical than star-struck. What most amazed Hazel was how pampered Oprah was: functionaries catered to her every whim. As for Elizabeth, who as a child had made her own clothes—including the immaculately pleated white cotton pique-and-gingham skirt she’d wore that first day of school, but was never to wear again—she’d still had her seamstress’s eye: the sleeves on Oprah’s pale gray knit dress, she noticed, were a mite too tight.

Surely, the women thought, Oprah would say something to them before the taping began, just to set them at ease, but she never did. Then, the cameras began rolling.

Reconciliation and redemption were usually Oprah’s things, but it soon became evident that here was one happy ending that was too much even for Oprah. Something about it, and them, seemed to offend her, and once on the air, she didn’t conceal her distaste for them. The famous picture flashed on the screen. “When we come back, how this shocking image of racism sparked a friendship, if you can believe that, 40 years later,” she teased.

“If you can believe that”: Elizabeth knew her relationship with Hazel had its skeptics, especially some blacks, including co-workers and some of the Little Rock Nine. (Knowing nothing about Hazel’s apology years earlier or her subsequent activities, nor caring sufficiently to learn about them, they assumed she was seeking atonement on the cheap or, worse, was just out for a quick buck. “Are you extremely gullible or are you just very, very forgiving?” one of them had asked Elizabeth.) But Oprah? The program resumed. “Elizabeth met Hazel for the first time two years ago in Little Rock, and now...they are friends,” Oprah said incredulously. She then repeated herself for emphasis: “They...are...friends. They are friends.” Now she sounded both indignant and resigned.

She turned first to Hazel. What had gone through her mind as Elizabeth showed up at school that morning? Integration, Hazel replied: her parents, along with everyone else she knew, opposed it. Elizabeth, who covered the photograph with a tissue whenever a student asked her to inscribe it, suddenly beheld it on a massive screen, and grew so distracted that she jumped when Oprah turned to her. “Do you still find it difficult to look at that photograph?” Oprah asked her sharply. “Obviously you do,” she quickly added, answering her own question before Elizabeth could, suggesting that this somehow reflected weakness. “It still causes a great deal of emotion,” Oprah went on in businesslike fashion. “Why?” Her tone was brusque, disbelieving: why, she seemed to suggest, hadn’t Elizabeth gotten over it already? “Because I am in that moment,” Elizabeth managed to say. Once more Oprah moved on fast. And what did Hazel feel? “Remorse. Regret,” she said. Embarrassed? “Yeah.” “’Embarrassed,’” Oprah repeated. The friendship had evidently been the subject of some skepticism, and snickering, backstage. “So what we want to know is how you all got to be friends after a photograph like that?” Oprah asked, suddenly affecting a folksy Southern accent: “y’all”; “FRAY-ends.” The two described their phone conversation more than 35 years earlier. “You called her because you wanted to say—what? ‘I’m sorry’?” “‘I’m sorry,’” Hazel replied. “Yeah, ‘I’m sorry,’” Oprah repeated. “Thank you both.” That was it. She seemed eager to be rid of them.

Afterward, Elizabeth felt that Oprah had gone out of her way to be hateful. She was forever talking about “standing on the shoulders of giants,” but in this instance she’d been as cold as she could be. Maybe, Elizabeth theorized, she’d reminded Oprah of something ugly in her own story; after all, she’d grown up in Mississippi, which was even more bigoted than Arkansas. Or maybe it was her appearance: she’d heard Oprah say once that bad teeth made her uncomfortable and, having only recently returned to work, Elizabeth had never had the money to straighten hers. As for Hazel, she knew some people either believed someone with so hateful a face simply couldn’t change, or didn’t want them to change: symbolically, they were more useful frozen in place. Oprah stepped off the stage and greeted her guests. She hugged Elizabeth, who by now was crying. She merely shook Hazel’s hand, saying nothing.

Superficially at least, Oprah had been on to something that day. Though their experiences on the program brought them momentarily closer together—each felt equally disrespected—the racial divide, comprised of misunderstandings, unrealistic expectations, harsh judgments, stubbornness, and hurt feelings—eventually proved too great for Elizabeth and Hazel to cross. Within a year, they had stopped speaking to one another, and with only a couple of exceptions—the last was Sept. 11, 2001, when Hazel, far from home, called Elizabeth for comfort—they have not spoken since. But talk to one about the other even now, and the bond between them, the one Oprah couldn’t accept or believe, clearly remains profound and deep. Perhaps at some point, maybe when no one is looking, they will come together again. One thing, though, is clear: It won’t be on Oprah.