Maxwell: I meet everybody. Wallace: You meet everybody … Maxwell: Everybody. Wallace: … and unless you have met somebody, he has not arrived … Maxwell: Not yet. —Mike Wallace interviewing Elsa Maxwell, 1957.

Fame is like a nightclub with the tightest door policy in town. The bouncer might let in a lucky few who look like they’ll add something to the mix. A handful squeak in as the plus-ones of guests already invited. Some bribe their way past the door and buy a few rounds, though no one enjoys drinking with them. Then there are the gatecrashers, who overwhelm the security and, once inside, prove so entertaining that their forced entries are soon forgiven.

But what about the folks at the back of the line who know they’ll never get in but are nevertheless determined to dance under the bright lights? If they’re named Elsa Maxwell they open a nightclub next-door and enforce an even tougher door policy.

Elsa Maxwell, the Iowa-born party planner, impresario, gossip columnist, etiquette authority, and press agent, to name but a few of her many job descriptions, made a career out of deciding who made the list. She was gifted at befriending rising stars and wealthy patrons and at introducing the former to the latter. Her acquaintances—from Noël Coward to Gary Cooper; from Maria Callas to Marilyn Monroe—spanned world wars and continents. She remained an active society figure right up to her death in 1963, at 82.

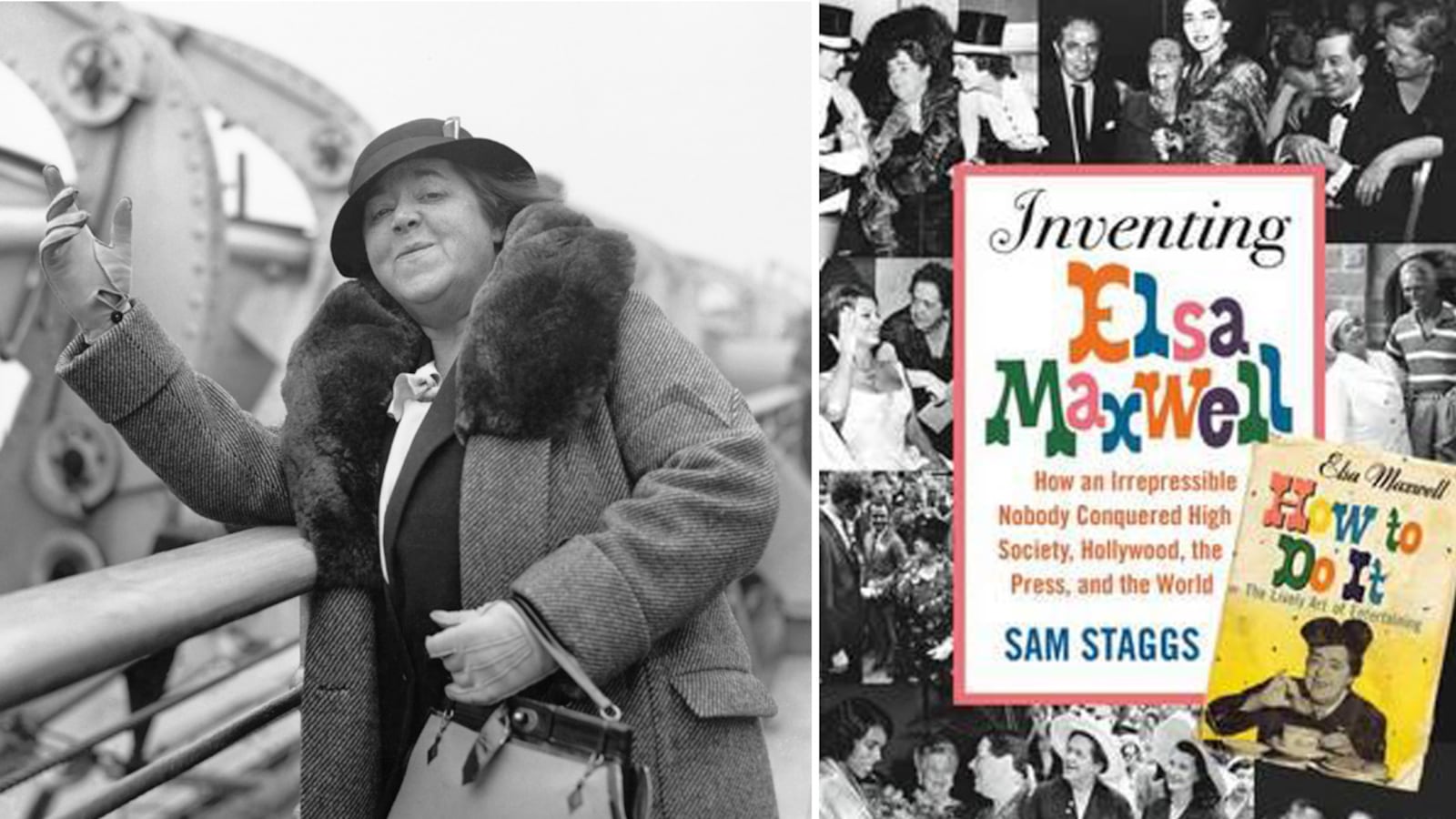

Maxwell was a large and unattractive woman. She would be the first to bring attention to her physique if she thought it might get a laugh or help her to portray herself as a self-made woman with no time for superficialities. “I’m no snob,” she would tell interviewers, using one of her favorite epithets. “And I’m certainly not vain. Just look at me—what do I have to be vain about?”

But a strange thing happened along the way. Relatively late in life, the fame-maker became famous. For what, exactly? Mostly for being Elsa Maxwell. This most un-telegenic woman became a screen star, enjoying cameos in campy films where she typically played either an exaggerated version of herself or a fictional society maven. With the emergence of television, an ideal medium for this walking sound-bite generator, she became a household name. Her self-effacing routines with Jack Paar, the 1950s king of late night, were a hit. She was an interviewer’s dream, a shameless namedropper and unabashed basher of fellow celebrities. Elvis Presley (“I’m not interested in pelvises or their movements”) and Jayne Mansfield (“she’s just a wash out”) were among her favorite targets. She was also prone to grandstanding and embellishment, claiming, for example, to have been born during a performance at the Opera House in Keokuk, Iowa, “yelling” as she put it, “louder than the dreadful mezzo soprano.” A fitting origin story for a woman who made a career out of her outsized personality and her ability to discern other talents. The story was a lie, of course, but as with so many tales she told, it made for good copy.

Tracing the reality behind such a celebrated personality presents a difficult task. The Maxwell biographer is faced with a subject who, while never hesitant to talk about herself, rarely allowed the public to see her true nature. Sam Staggs, in Inventing Elsa Maxwell: How an Irrepressible Nobody Conquered High Society, Hollywood, the Press, and the World, does an admirable job, providing an entertaining account of this fabulous and fabulist life. While in many ways Maxwell emerges as a harbinger of our own meta-celebrity culture, Staggs counters the popular perception of her as a mere “party girl” or dilettante. He chronicles the decades of work, especially in the ’20s and ’30s, that went into building the persona that became so well known by the ’50s.

Staggs reveals that despite Maxwell’s well-honed “just a poor girl from Iowa” routine, her family moved from Iowa not long after her birth and she spent much of her childhood in the plush environs of San Francisco’s Nob Hill. While enjoying some early success as a songwriter, she had enough of an ear for music to know that she was not gifted in this capacity. Her true talents lay in spotting the genius of others (she was an early champion of Cole Porter’s), and, especially, in getting the right mix of luminaries together to have a good time. Her brashness, inventiveness, and inexhaustible energy carried her the rest of the way.

The range of her accomplishments is astounding. She tried her hand as a theatre impresario in San Francisco before the Great War, and went on to host high society soirées in Paris afterwards. “What most people regard as amusing interludes were to Elsa a profession,” remarked one of her acquaintances. Who else could claim to have run a Jazz Age nightclub in the City of Light with the designer Edward Molyneux; to have transformed the Lido in Venice from a drab getaway for Italian families on a budget into a high-end resort; to have helped make Monte Carlo the hottest summertime gambling destination of the 1920s? Perhaps Maxwell’s greatest contribution to humankind is that she invented the scavenger hunt, one of the many silly gimmicks she would draw on to ignite her celebrity-filled fêtes. One of her most memorable ploys was the infamous “Hate Party” she threw in Paris in the ’50s, where guests arrived dressed as the people they most despised. Elsa came as King Farouk, who had earlier sued her for defamation of character.

As with many people who turn their personalities into bankable brands, Maxwell clearly felt the need to be all things to all people. In her memoir she boasted of selecting a dinner-party menu with such refinement that she impressed even the Ritz’s famously glacial maître d’hôtel Olivier. Then, on the same page, she confided that because she was so nervous about the party, the meal “tasted like ashes,” and she dismissed Olivier as “the world’s greatest snob.” Only an expert fabricator could survive the public tightrope walk required of someone trying to portray herself as both the taste-making doyenne of European society and a self-effacing American nobody. Maxwell’s stance towards her own sexuality was equally ambivalent. In her own memoir she railed against what she described as “the shocking increase in homosexuality as further evidence of decadence in the top levels of American society.” Yet she lived with another woman for nearly half a century, a companionship that Staggs suggests was a loving and stable, if open, marriage.

Spending as grandly as she earned, if Maxwell needed ready cash she might hawk some expensive gift or ask one of her highflying pals for a loan both parties knew would never be repaid. Staggs quotes one such friend, Jack Warner, who, after Maxwell’s death, wrote about a sum she hadn’t repaid: “I really don’t mind. Because wherever she went there’s going to be action, and she’ll spread that cash around with happiness.”

It is pleasant to think of how much happiness (though surely much cattiness as well) Maxwell spread through the roughly 3,000 parties she hosted. Near the end of her life, she summed up her legacy by saying that while she had no money and no possessions, she had “more friends than any living person. They are my riches.” Her words were not simply empty sentiment, or yet another playful untruth. With each new boldface name she charmed, the plump girl from Iowa gleefully wrangled her way closer to the front of the line. “She died happy,” as one obituary writer put it, “as undisputed ringmaster of the international society circus.”