The following is an excerpt from "The Last Pirate: A Father, His Son, and the Golden Age of Marijuana" by Tony Dokoupil (Random House). Reproduced with permission.

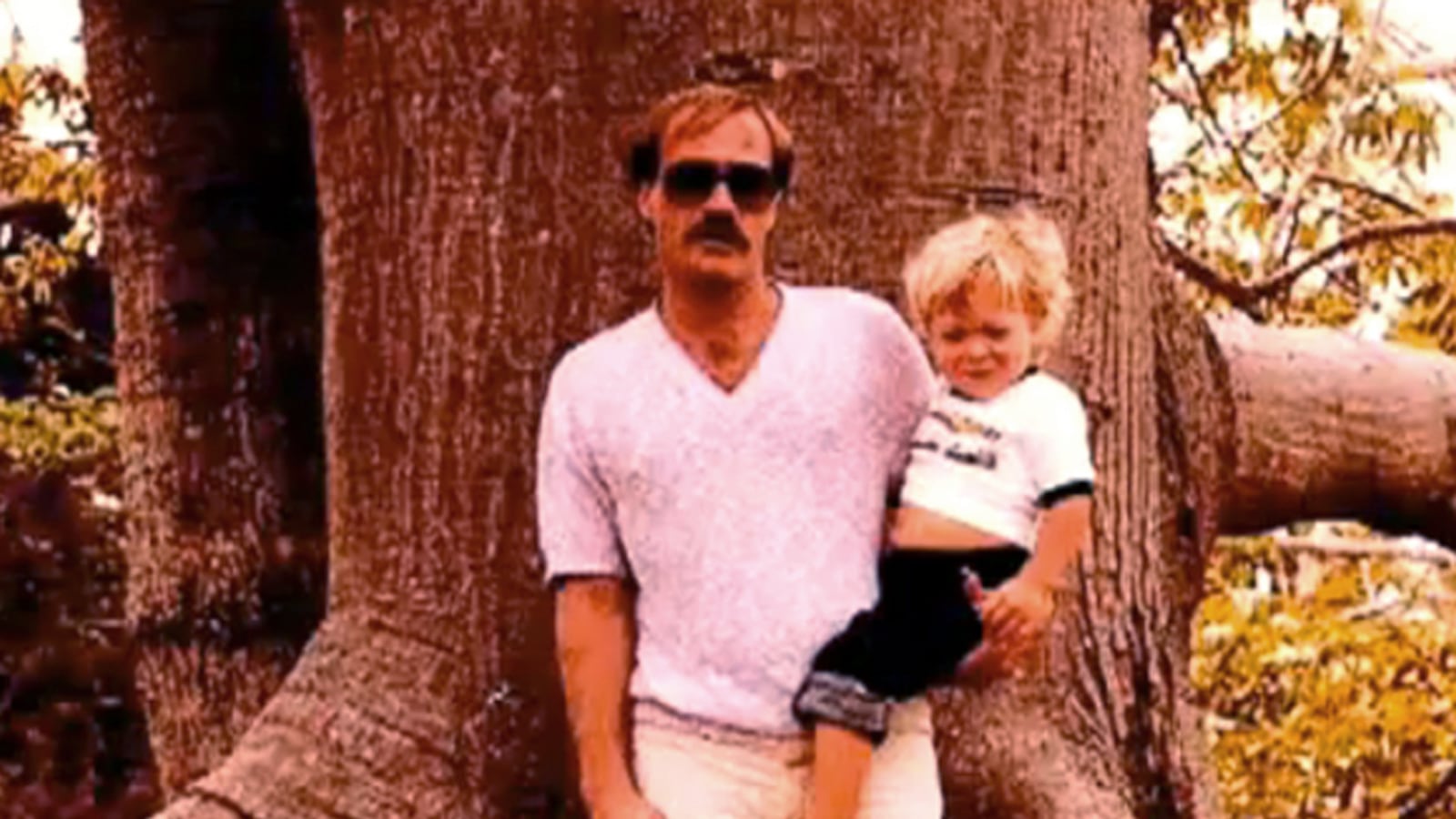

My father and I are separated by only an adjective—Big Tony, Little Tony—and when I was truly little we toured Miami with our seamless tans, windblown blond hair, and Lacoste swimsuits. My father liked daiquiris, virgin for me and an extra shot of rum in the straw for him. He also liked girls, and he liked how approachable he was with a toddler staring awestruck from the next stool over.

His first drink would disappear as fast as a cup of ice melt tossed into a breeze. But he sipped the second one, pushing aviator shades onto his head. His face got interesting then, his features adrift, and he would start talking to people. Dad liked hostesses in particular.

Hostess: “Would you like our special shrimp sampler?”

Dad: “I’d like to take a shower with you.”

If you smoked Colombian weed in the 1970s and 1980s, I owe you a thank-you card. You paid for my swim lessons, bought me my first baseball glove, and kept me in the best private school in south Florida, alongside President George H. W. Bush’s grandsons, at least for a little while. But the truth is, I never really knew my father, not as a man, not as a person distinct from the figure I idolized in the abstract. For the early years of my childhood, he was someone I adored. He taught me how to hit a baseball, read a newspaper, and shave (without the blade). By the time I was old enough to care about those things, he was long gone, leaving only stories behind.

At the Grand Canyon, he let me crawl to the edge for a better look. During a trip to New York in the dead of winter, he dared me, aged four, to lick a Central Park slide; my mother had to pour hot-dog stand coffee on my tongue to get it unstuck. At Disney World he let me watch movies alone in the hotel room, where I fielded a call from my mother while he hit the bars. In Miami we sometimes played baseball using a big orange basketball, which sure was easy to hit but not so forgiving. The bat bounced hard off the ball, right into my mouth. It looked like Halloween when I flicked the light on in the bathroom.

As an older kid in Miami, if you asked me about my father, I would have told you he can’t come to career day. He’ll have to miss the father-son brunch. His work is in New England, where all the antique-furniture auctions are held, or he’s in Vermont this month, where he develops property. I might have said he’s in Key West, where he zips snowbirds into their wet suits or St. Thomas where he spits into their dive masks. If we were friends, I might have told you he was in rehab, and that would have been the truest possible answer.

I never knew the full truth. For most of my adult life, I had only scraps of information about my father. Some were fun, like streamers left behind after a party. Others were dark, like bats from the mouth of an unmapped cave. My mother almost never spoke of him, but I knew that he did drugs, sold weed, slept around, and bottomed out so completely that friends presumed him dead long before he was forty. My mother advised me to assume him dead as well. But I did the opposite.

As a teenager, I recoiled from this image of my father as a violent mess, and I began to build a better version in my own mind. A heartsick boy can compose a small, speculative history of manhood from a few black-and-white photographs and a knife left behind in a drawer. Such was the style of my own imaginings: I told people my father was a cross between Tony Montana and Willy Loman, a big-time drug dealer, licking his wounds somewhere in Colombia. I could accept this vision of him, and anyway, I needed it to survive. High school is hard enough without having to wonder about the blood you have, the brain you’ve inherited.

When I was twenty, I felt established enough to face the truth, so I called my father. He refused to see me. After a few letters, he changed his mind but I refused to see him. Each of us backed away reflexively, as though closing the door of an occupied bathroom.

I was almost thirty, and years into a journalism career, before I was ready to talk to my father again. Peering over a notebook this time, I saw him as a character in a larger story about outlaws. In a digital age, hackers and Internet pranksters are the mantle bearers, people whose work is massively influential but rarely romantic, almost never sexy. There are no grand vistas, no beer-commercial-grade photo ops, no tradition of carousing and womanizing, winning it all and losing it fast. There are no deathless pop songs about computer keystrokes.

And this criminal awe deficit, as I saw it, was the starkest in the weed business, where yachtsmen and beach bums like my father have been replaced by businessmen and botanists. Bronze skin and corn-colored hair have faded into cubicle complexions and cowlicks. Where there was once the thrill of foreign fields, leaky boats, and suburban stash houses there are now indoor “seas of green” and legal channels to market. I believe something was lost in this shift. Weed is undeniably better today—every bud is a green chandelier of head-ringing crystals—but it’s infinitely less interesting.

Many of the old smuggler-dealers have come to the same realization. They see themselves as the last great outlaws, a people for whom pirates are idols and criminal vitality is the only worthwhile kind. They see themselves as heroes, in other words, righteous flouters of a silly prohibition. And they sure hope you will agree. My father and members of his ring are no different, which is why almost all of them were willing to talk with me. A sign of how little things change is that all but my father asked me to disguise them. I was happy to do so. These friends and family have given me a true story if not an honorable one. It’s a public saga complete with a real pirate’s booty: more than a million dollars lost, buried, or stolen. It’s also a private pursuit that’s more important to me with each day.

See, I recently became a father myself. We had a boy and it didn’t take long before I saw what I was up against. On my very first Father’s Day, in fact, my infant son came home from day care with a preprinted poem, a trifle called “Footprints.” Millions of dads probably got the same lines, giving them no more than a sidelong glance before dinner. But the poem set off tiny sticks of dynamite behind my eyes. It contains every immutable truth our society pushes—and I fear—about fathers and sons mimicking each other through the generations. It ends with the most painful idea of all, a repetition of the lines “walk a little slower, Daddy, for I must follow you.” I think it’s the “must” that really stabbed my heart.

I, for the record, am not an Anthony, either on my birth certificate or so far in life. But my father still haunts me, making me terrified of the genes I carry and the man I may become. There must be a way out of this loop, I decided, so one day I set about finding it in the arc of my father’s rise and fall. This is a personal story but also a story of generational change, of talents wasted and talents redeemed. It’s specific to my father’s experience but also representative of what I believe many children of the 1970s and ’80s feel as descendants of the Great Stoned Age, the greatest explosion of illicit drug use ever recorded. I’ve tried to write a broad chronicle of marijuana-smoking, drug-taking America rather than a closed circle of family woe. Everybody knew a drug dealer back then. This is the life of one of them and, in a pharmacologic sense, the story of us all.