In recent years, there has been a rush to remember AIDS, to capture its specifics on film and in galleries, to memorialize those we lost and honor those who survived. Given the ongoing nature of the AIDS crisis, this is no easy task. We live in a culture where the past is seen as a dead thing, a set of names and dates to be memorized—and then forgotten.

So no wonder AIDS activists are wary of our present memorializing impulse, when more than 35 million people around the world now live with AIDS.

At best, the study of history is a close examination of the forces that created a particular moment in time, which helps us better understand the workings of the world. At worst, it is a petting zoo, putting on display sanitized versions of real life that conform to our preexisting biases and beliefs. Instead of a window, we use history as a mirror, and like toddlers, we clap joyfully at our own reflections, naively believing we have engaged with something real.

Thankfully, the New York Public Library show “Why We Fight: Remembering AIDS Activism,” open now through April 2014, offers a good example of what an engaged historical exhibit on AIDS might look like.

Entering the library’s small Wachenheim Gallery is like returning to a time when AIDS activism was wheat pasted across the city in black, white, and shocking pink. Even when empty, the room is never quiet. Instead it is filled with the hushed echoes of protests whose political, social, and communal reverberations are felt today. Aesthetically, “Why We Fight” perfectly recalls the fevered early years of AIDS activism.

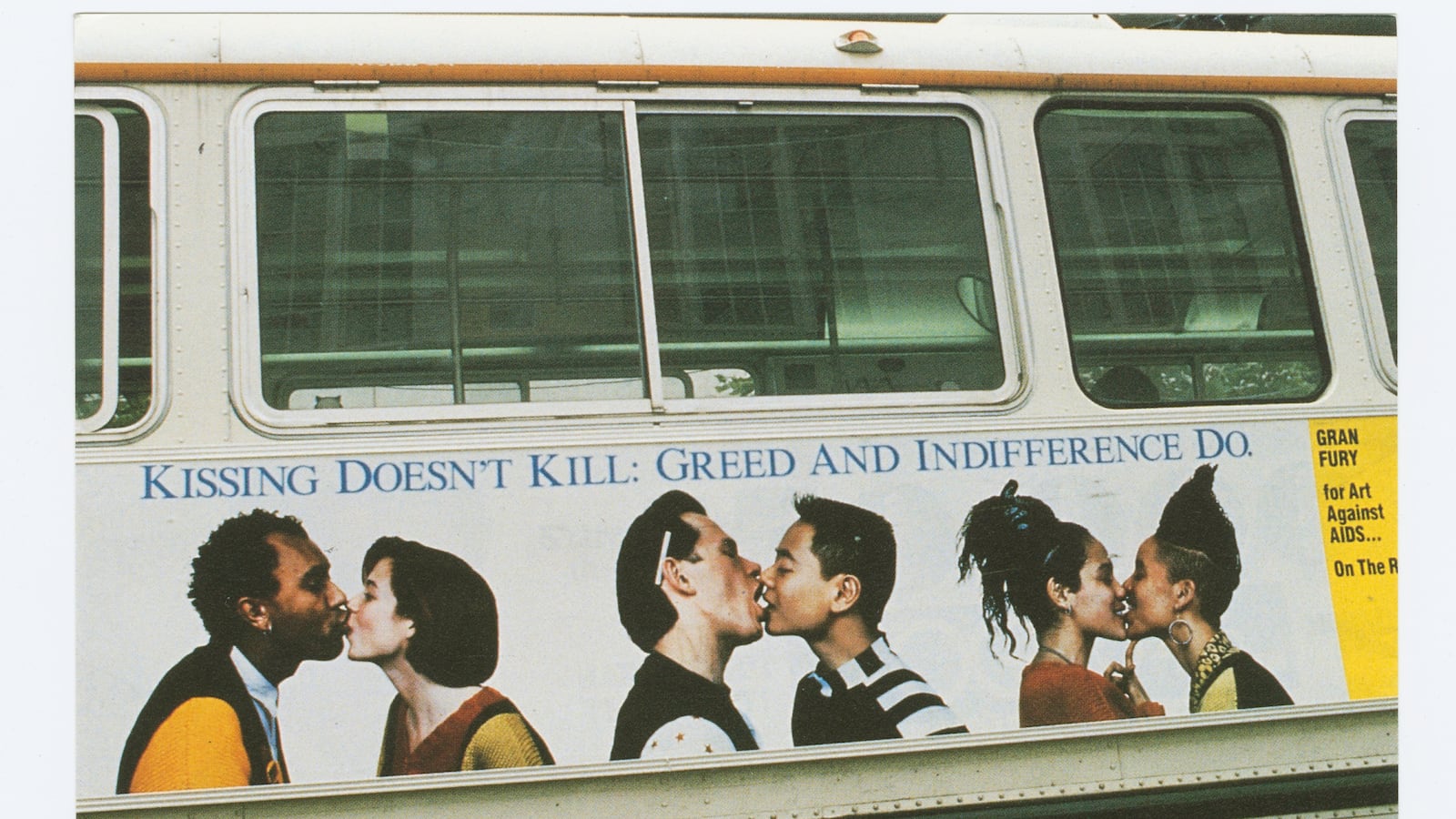

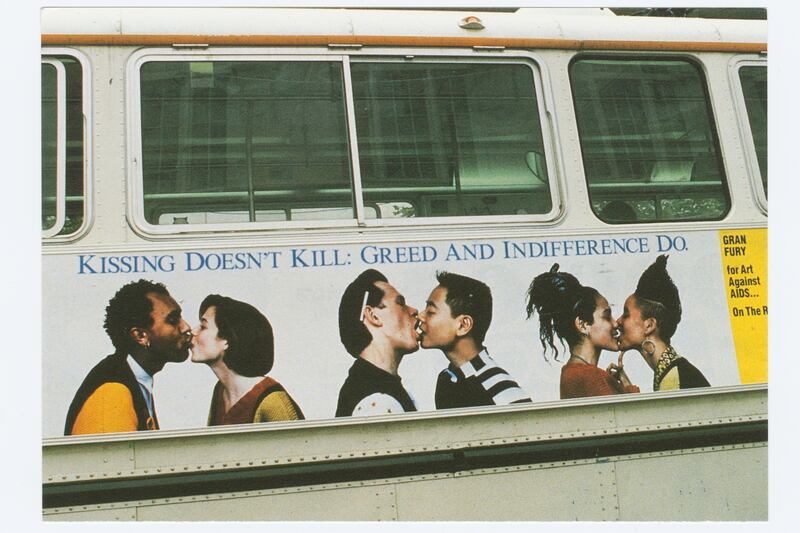

Such accuracy should not be so surprising. To create the show, the library drew on its vast repository of AIDS and queer activist holdings, including the archives of the People With AIDS Coalition, Gay Men’s Heath Crisis, ACT UP New York, The International Gay Information Center, and the AIDS activist art collective Gran Fury, all of which are easily accessible to the public at the library’s main branch on 42nd Street. Laura Karas, one of the two curators, processed much of the material herself. Jason Bauman, the other half of the curatorial team and the library’s coordinator of LGBT Collections, was involved with both ACT UP and Queer Nation throughout the 1990s. Thanks to the library’s five-year-old LGBT initiative, more than $2.5 million has been raised to collect, preserve, and present just such material.

Good funding, knowledgeable curators, and institutional support are the hallmarks and harbingers of well-told history, and viewing “Why We Fight” will serve as a stark reminder of how rarely these preconditions are met in other mainstream exhibitions on AIDS.

The story told on these walls is a fractured and fractious one that consciously resists an easy narrative. The curators have eschewed a traditional chronological mode of storytelling, which might suggest that later kinds of activism were more “evolved” or “effective,” and chosen instead to divide the show thematically. In their telling, Baumann and Karas give primacy to the lived experiences of AIDS activists, writing in the opening panel that institutional responses “lagged behind the passionate work of dedicated individuals who tended the sick, challenged prejudices against people living with HIV, educated their communities, and fought for resources and research.”

This “passionate work” took many forms, as Baumann and Karas take great pains to show, from safer sex comics to street protests, from caring for the sick to fighting for education reform. Many of the organizations invoked in this installation may not be familiar to viewers who see “ACT UP” and “AIDS activism” as synonymous. Some, such as Gay Men of African Descent, have been rendered invisible by less meticulous exhibits that narrowly conceive of AIDS activism as only that work done by single-issue groups devoted to fighting the crisis. Others, such as the Mattachine Society, are usually left out because they folded prior to the onset of AIDS, even though their groundbreaking social justice organizing on behalf of LGBT people critically set the stage for much of the AIDS activism that was to come.

What won’t viewers find in “Why We Fight”? Any of the homophobic trademarks of other mainstream historical exhibits on AIDS. There’s no opening invocation of the slutty ’70s to suggest that we brought the crisis on ourselves; no soft-focus photos of infants to help us differentiate innocent victims from punished sinners; no blaming the slowness of the public response on queers who remained in the closet out of fear, confusion, familial pressure, or self-hate. And, perhaps most important, there’s no dancing around the crisis’s primary cause, which was and is our country’s apathy and antipathy toward the suffering of queer people, drug users, the poor, sex workers, immigrants, and people of color.

Some have criticized “Why We Fight” for not showing more contemporary activism, and rightfully so. More could have been done to draw the timeline of this show into the present. However, this void is partially filled by exciting public programming, including panels with activists such as Sarah Schulman and Avram Finkelstein, sexual health are workshops for teens, and numerous film screenings.

But the show itself is a kind of contemporary activism, and not just because it illuminates parts of history that are already on the verge of being forgotten. It is a signal flare fired from the archives, a reminder that despite years of misinformation, repression, and persecution, this history has survived—and it can be accessed, free of charge, by anyone.