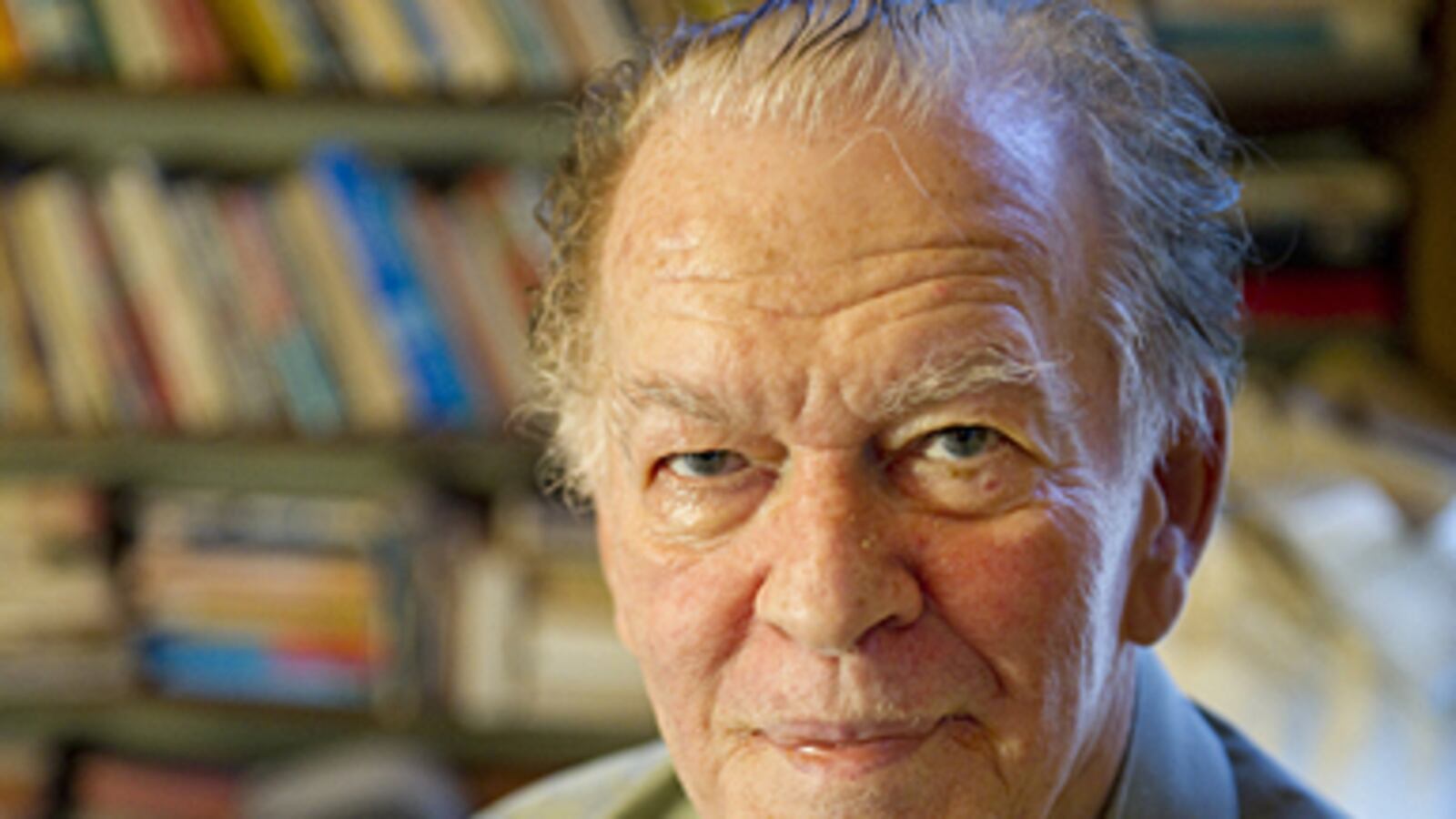

There are many roots of the Egyptian revolution. But one of the most unlikely goes back to an East Boston rowhouse, where an 83-year-old named Gene Sharp runs a shoestring operation called the Albert Einstein Institute—and arguably just changed the course of history.

For the last half century, Sharp has been writing about nonviolent protest, and trying to make his ideas accessible to dissidents the world over. No mean feat, given that his signature work, The Politics of Non-Violent Action, weighs in at 900 pages and was published in 1973. But it’s working. Thanks in part to a distillation of his ideas entitled From Dictatorships to Democracy, which can be downloaded from Sharp’s website in dozens of languages, his gospel of upheaval has apparently become essential reading for budding revolutionaries in Cairo and parts beyond.

Ahmed Maher, a 28-year-old construction engineer, was one of the young Web-savvy upstarts who helped set in motion the protests that last week ended Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. Maher, of the April 6 Movement, looked to Serbia’s democratic movements for inspiration. There, he found Otpor, a protest group which helped take down strongman Slobodan Milosevic. From Otpor, the young Egyptians discovered the teachings of Sharp, who urges nonviolent resistance as the most efficient way to topple dictatorships.

Sharp says he hasn’t been directly in touch with anyone in Egypt since the uprising began late last month. But he says he is happy to know that his ideas may have had some influence.

“I’m very pleased,” he says. “I’ve been studying this question of dictatorships for many decades. It is a lonely struggle. To get this kind of recognition is very important.”

Among his less-conventional suggestions for protest, Sharp has advocated the “Lysistratic nonaction,” in which women use sex as political leverage. He’s also called for disrobing and skywriting as political statements.

• Peter Beinart: America’s Proud Egypt Moment• Niall Ferguson: How Obama Blew Egypt• Full coverage of the Egypt revolutionThe pro-democracy advocates aren’t the only ones who’ve noticed. In 2007, Hugo Chavez accused Sharp of being part of a CIA-led conspiracy to overthrow his government. The following year, Iranian officials made a similar charge, alleging that the former Harvard researcher was working hand-in-hand with the likes of John McCain and George Soros to foment rebellion in the country. (The paranoia is perhaps understandable; thousands of copies of From Dictatorships to Democracy had been downloaded in Farsi in advance of protests that flooded Iran’s streets in 2009.) The Burmese felt similarly hoodwinked by the solitary scholar. Sharp first published his manual to resistance, which teaches 198 methods of nonviolent action, in Myanmar.

His advice is particularly granular, giving instructions from how "rude gestures" can function as "symbolic public acts" to using "guerrilla theater" as a form of "social intervention." According to one take, Sharp’s Albert Einstein Institution is “a U.S. intelligence asset used to spark ‘nonviolent’ regime change around the world on behalf of the U.S. strategic agenda.”

In most interviews, Sharp holds up the shabby state of his institute as a sign that he’s not in the cahoots with George Soros or anyone at the CIA. Lately, he had to let go of most of his staff.

“We are very small and very poor,” he says.

Not that Sharp isn’t without his benefactors. One former student, the financier Peter Ackerman, once told The Wall Street Journal that he’s given his mentor’s institution more than $10 million over the years. In 2004, the pair had a falling out.

These days, Sharp says, resistance leaders usually find him.

“We get news from all over the world. We never know where the next phone call will come from, what part of the world,” Sharp says.

Among his less-conventional suggestions for protest, Sharp has advocated the “Lysistratic nonaction,” in which women use sex as political leverage (a ploy adopted in Kenya in 2009, in an activist-led drive to stop government infighting). He’s also called for disrobing and skywriting as political statements.

Sharp argues that dictatorships share certain traits throughout the world—making it easier to tailor a one-size-fits-all approach. But he’s not blasé about what happened in Cairo last week; he ranks the fall of Mubarak as “at the top” of democratic revolutions he’s witnessed. And he’s confident that the spirit shown in Tahrir Square won’t end there.

“People are learning that they don’t have to be afraid,” Sharp says. “The fear is gone. People can see the example. The Egyptian example will be imitated elsewhere. We don’t know where, but it will happen.”

Samuel P. Jacobs is a staff reporter at The Daily Beast. He has also written for The Boston Globe, The New York Observer, and The New Republic Online.