He’s alive!

For months, Mitt Romney has been little more than a specter haunting the GOP, tucked away in La Jolla, California, never appearing on television, and rubbing shoulders with his fellow Republicans only on the rarest of occasions.

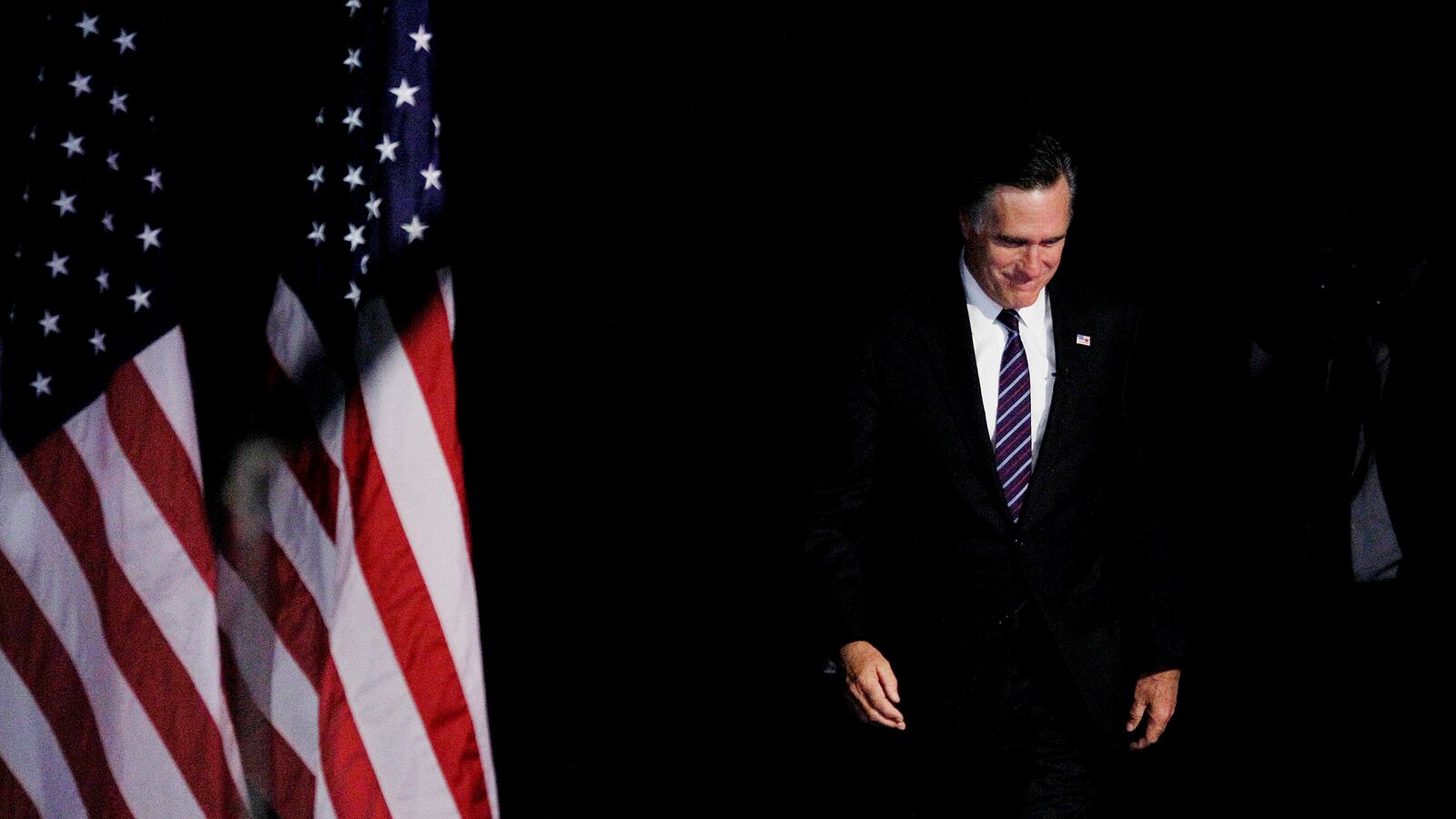

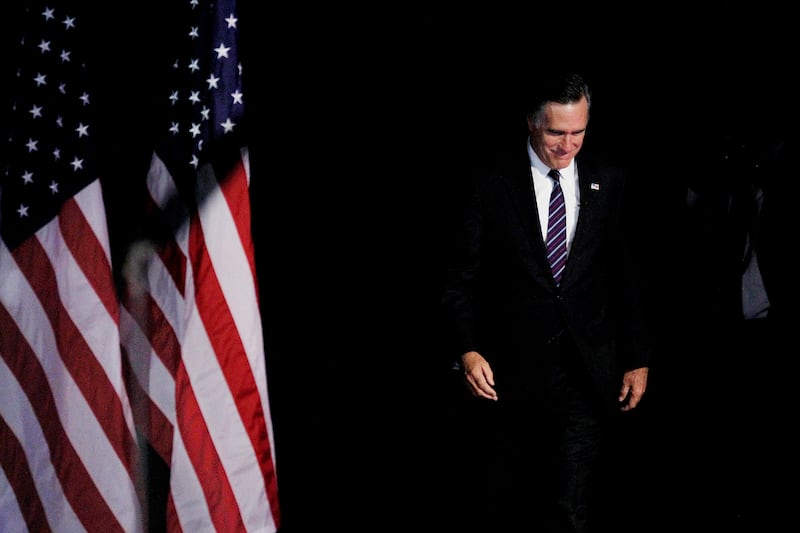

But nearly four months after Romney conceded the presidential election with a meek send-off in a half-filled Boston convention center, he is venturing out again, slated for a speaking spot at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference.

The moment is being billed as Romney’s reemergence, but the truth is he never really left. Even though he hasn’t been seen, Romney has been hovering, ghostlike, over the Republican Party since November.

The phantasm was there in Sen. Marco Rubio’s response to the State of the Union address. The Florida Republican assured listeners that Democrats, just like Republicans, love America and talked about living in “the same working-class neighborhood I grew up in.” That was contra Romney, who reminded campaign audiences that his voters, at least, were motivated by love of country. He also had trouble living down his car elevator and his stated enjoyment of firing people.

Romney hung, wraithlike, over Bobby Jindal, when a few months after the election the Louisiana governor told a gathering of Republican grandees, “The first step in getting the voters to like us is to demonstrate that we like them.” He added, “We’ve got to compete for every single vote—47 percent and the 53 percent,” a hardly shrouded reference to Romney’s infamous comments at a Florida fundraiser.

And now, as Republicans emerge in the early earliest days of the next presidential cycle with their own proscription to fix what ails the GOP—Eric Cantor one week, Paul Ryan the next, Jeb Bush the following—the one thread linking each diagnosis is plain: WE ARE NOT THE PARTY OF ROMNEY. To lead the party in the future, candidates must be everything Romney is not: not old, not rich, not white, not Northeastern, not living down any past apostasies. Only then can the right potion be discovered to exorcize the ghost of Romney for good.

It used to be that losing presidential contenders were seen as still relevant. Think of John McCain, who remains a spear for Republican senators. Sometimes, as in the case of John Kerry and Al Gore, the losers were considered frontrunners the next time around. Or, in the case of Bob Dole, they retired to a sort of a bipartisan eminence and were mostly forgotten.

But Romney has been doing more to define what the party stands for—albeit as a mirror-image example—than he ever did while running for president. The memory of his candidacy is forcing the party to confront its weaknesses in a way that his real candidacy never could.

“People didn’t blame McCain,” says John McLaughlin, a GOP pollster. “But in this case you had high unemployment, a flat economy, a president that wants to raise taxes, a cover-up in Benghazi, and a president willing to make defense cuts. The stakes were so high, and we thought we were going to win. It is just really aggravating to Republicans.”

One reason the former governor’s shadow is lingering: unlike McCain and Kerry, Romney did not have a political role to fall back on after Election Day. Their losses were equally painful to the party faithful, but they were able to take up the fight again as soon as the next legislative session began. Nor was Romney a beloved figure. Lacking the irreproachable personal biography of a Bob Dole, he was known mostly as a ferocious intraparty brawler who tore down Rick Perry, Newt Gingrich, and others. Romney was seen as a transitional figure by party stalwarts, someone who could tide them over until the deep bench of 2016 was ready.

So like all the great ghosts—think Freddy Krueger, Jason, Casper—the tragedy of 2012 just won’t go away.

“The thousands gathered at CPAC this year are eager to hear from the former 2012 GOP presidential candidate at his first public appearance since the elections,” said Al Cardenas, chairman of the American Conservative Union, in announcing the former governor’s appearance. “We look forward to hearing Governor Romney’s comments on the current state of affairs in America and the world and his perspective on the future of the conservative movement.”

Cardenas appears to be alone in that sentiment.

“I wish he wouldn’t speak at all,” says one top Romney fundraiser. “I mean, what’s the point? It is time to focus on the future.”

A number of Republicans who spoke to The Daily Beast suggest that Romney, by at last coming up for air, could begin the process of exorcizing his campaign’s memory from the party’s consciousness. Freed from the shackles of a campaign, he could shed the part of him that claimed to be “severely conservative”—the guy who professed to love small-varmint hunting and NASCAR (or at least, car owners) and advocated for “self-deportation.” Instead he could tell Republicans what it will take to begin winning elections.

Or he could set the whole process back again.

“It could really go either way. On the one hand, it could be a cathartic ride off into the sunset, or he could try to relitigate the campaign or rehabilitate his image and defend the indefensible, and it could overshadow the speeches of a Jindal or a Rubio that really are the next generation,” says Matt K. Lewis, a conservative columnist who was one of the first after the election to call on the party to reevaluate itself. “There is a lot of excitement about this next generation, and this is like a bad relationship that didn’t work out. No one wants to look at those vacation pictures again. You just want to forget what happened. This is like bumping into her mom at the grocery store and hearing about her.”