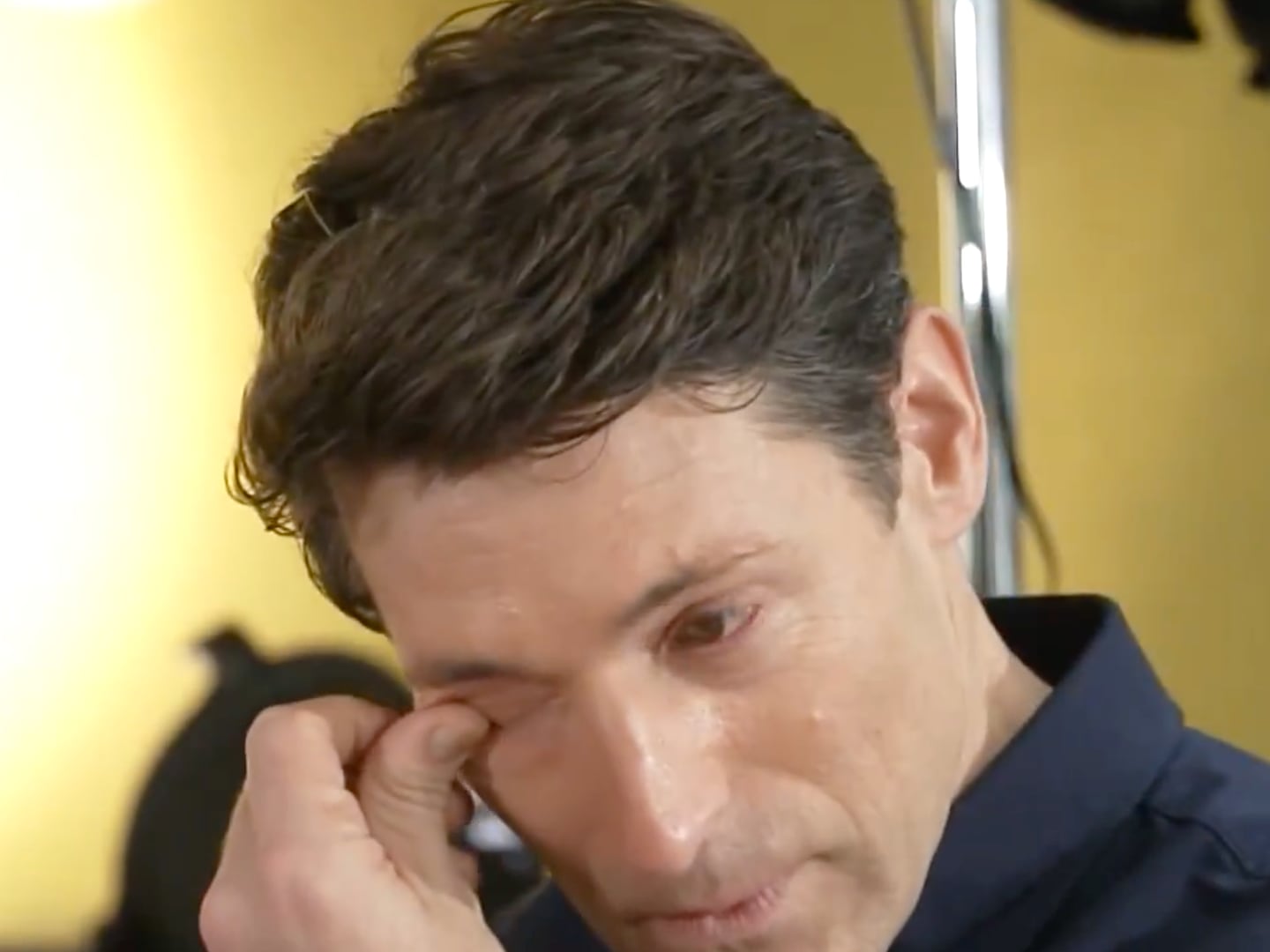

I like to cross my legs, not with one ankle on top of the opposite knee, like the straight man I am supposed to be, but with my legs closed, like Kurt Hummel, the flamboyantly feminine gay character on Glee. Like Kurt, I cry often, far too often for a heterosexual man. I like flowers and dancing and care deeply about fashion–of course, so does Kurt.

Kurt Hummel is a stereotype. And he is my hero.

After enjoying a honeymoon with critics during the first half of its premiere season, Glee is now increasingly coming under attack for its presentation of standard images of minority groups, especially in the character of Kurt. He is “that oldest of clichés: the sensitive gay boy who really wants to be a girl,” writes Ramin Setoodeh at Newsweek.com. Kurt and other stereotypical gay characters are setting back the movement for “acceptance” by being “loud and proud” at a time “when standing apart seems particularly counterproductive.” Fearing that unabashed flamboyance will cause heterosexuals to more fiercely defend marriage and the military “against what they see as a radical alteration,” Setoodeh argues, “if you want to be invited to someone else’s party, sometimes you have to dress the part.”

For heterosexuals, the movement begun by unabashed queens and dykes transformed life in countless ways.

Chris Colfer, the actor who plays Kurt Hummel, recently acknowledged his fear of making the character aggressively gay. “I’ve been working really hard to have him not be a stereotype from the beginning,” he told Brett Berk at Vanity Fair. “I grew up in a conservative small town, and the gay characters I saw on TV and in movies when I was growing up were all flamboyant and obnoxious and sometimes kind of annoying. And they weren’t like anyone I knew. The gay people I knew in real life were soft spoken and didn’t want to call attention to themselves because they were terrified of exposing themselves, of people finding out that they’re gay.”

Colfer is a wonderful actor, but if his intention is to portray a boy afraid of exposing his sexuality, he is doing a miserable job. Several gay bloggers have complained that Kurt “is just too gay,” and Berk writes, “Kurt is so gay he is, as he says, ‘an honorary girl.’” Indeed, and for this we should be glad.

History tells us that those unafraid to be “too gay” won far more freedoms–for all of us–than those who dressed the part of straights.

• Andy Dehnart: Glee’s Harmful Simplicity • Gallery: Celebrity Gleeks The strategy of hiding stereotypical characteristics was undertaken by the first gay rights organizations in the United States–the Mattachine Society, the Daughters of Bilitis, and the Janus Society, which were founded in the 1950s. Members of the groups were required to wear business suits and conservative dresses. Drag queens, “bull dykes,” “swishing,” and “limp wrists and lisping” were explicitly barred from their meetings and demonstrations. The Mattachine Society instructed gays to avoid “any direct, aggressive action” for civil rights and attacked the “swishy type of homosexual who brought contempt and derision on the majority of homosexuals.” The Janus Society urged “all homosexuals to adopt a behavior code which would be beyond criticism and which would eliminate many of the barriers to integration with the heterosexual world.” The groups even avoided using the term “gay.” Instead, they called themselves “homophiles.”

Many have argued that the “politics of respectability” was necessary in the conservative era of the 1950s and early 1960s. But it was a total failure. Police raids on gay bars actually increased, no civil rights were won, and by eliminating the most powerful form of sexual dissent in American culture, the homophiles’ strategy actually contributed to the sexual conservatism of the time.

All that changed on June 28, 1969, when a group of flamingly stereotypical and self-proclaimed “faggots” and “dykes” refused to be arrested during a police raid at the Stonewall Inn in New York City. A newspaper reported that “Wrists were limp, hair was primped,” as drag queens in high heels and butch lesbians wearing crew cuts and leather jackets threw bricks and bottles at cops and set fire to the building. Several of the male rioters confronted the police with an impromptu chorus-girl kick line, singing, “We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We don't wear underwear/ We show our pubic hairs.”

That night, and in the years that followed, the aggressive presentation of stereotypes broke open ideas of what it meant to be a man or a woman and widened the sexual possibilities for a generation of Americans—gay and straight.

After the Stonewall rebellion, city governments across the country ended police harassment of gay public spaces. Within a few years there were hundreds of openly gay, fully legalized bars and bathhouses in the United States. The word “gay” was used in the names of countless activist organizations and newspapers. The American Psychiatric Association removed the category of homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Universities established gay and lesbian studies programs. And hundreds of thousands of men and women gathered regularly for massive, public coming-out parties and “pride” parades in cities from coast to coast.

For heterosexuals, the movement begun by unabashed queens and dykes transformed life in countless ways. Through the 1960s, psychologists–and Americans generally–believed that an individual was either masculine or feminine. Shortly after Stonewall, the psychological profession adopted the Bem Sex-Role Inventory, a scale that measured masculinity and femininity as separate and coexistent. Americans began to speak not just of feminine and masculine personalities but also of “androgynous” types—people who were both masculine and feminine, or neither.

For those of us who feel free to exhibit behaviors outside those assigned to our sex and sexual orientation, we have stereotypes like Kurt Hummel to thank.

Thaddeus Russell is the author of the forthcoming A Renegade History of the United States (Free Press/Simon & Schuster, 2010). He teaches history and cultural studies at Occidental College and has taught at Columbia University, Barnard College, Eugene Lang College, and the New School for Social Research.