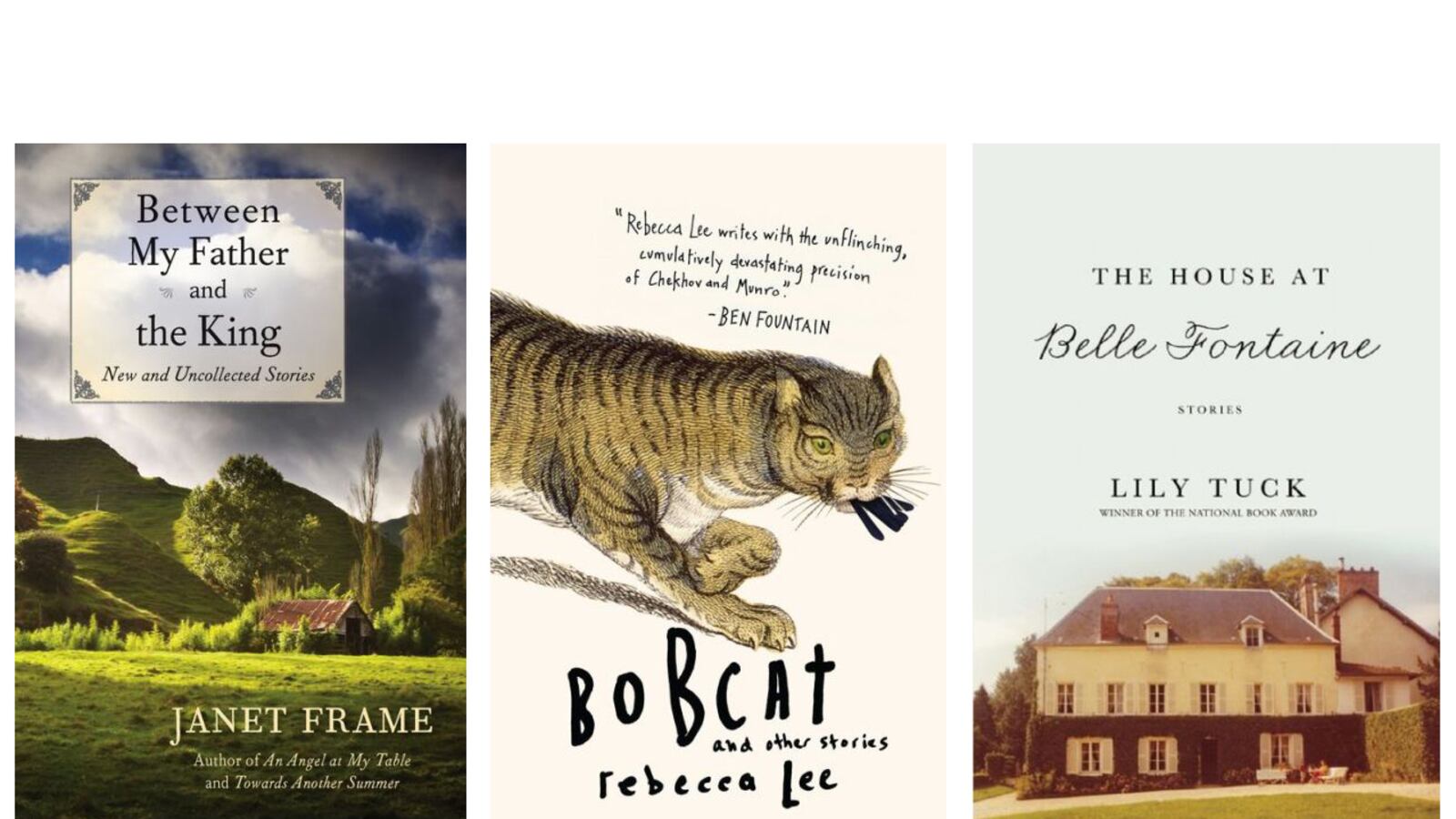

BobcatBy Rebecca Lee

For sheer reading pleasure, Bobcat is at the top of my late spring list for first story collections.

The title story is a tour de force set at a New York dinner party. The hostess and host—a human rights lawyer pregnant with their first child and a novelist whose latest involves a war correspondent who sleeps with three women in the first 40 pages—wrestle a rosemary-infused roast from the oven. She and a childhood friend, also a novelist, worry about a third woman’s cheating husband. Meanwhile, an editor awaits a Salman Rushdie manuscript so she can make a bid in the morning, and a woman describes the subject of her memoir: how she lost her arm in Nepal—“The bobcat stalking her through the foothills, coming upon her kneeling over a small pond, and placing his paw on her shoulder as if to say, politely, Hello?”—and the surprising joy she felt “when blood leaks out of a body, the body loses its pulsing internal clock, and all understanding of time is released. The soul becomes loosed from the body and unhinged from time simultaneously and begins to roam freely about…” And the pain? That comes at the end of the story, out of nowhere. (Well, not exactly.)

Another story in the collection, “Fiala,” which won a 2001 National Magazine Award for fiction, is set at an invitation-only workshop headed by Nostbakken, a legendary Midwestern architect whom his student, the narrator, envisions as a wistful man who stares off into the distance, “imagining a building that might at last equal nature—generative and wild, but utterly organized at the heart.” Lee conjures up a love triangle between the narrator, Nostbakken, and one of his other students. Side stories include a transcontinental arranged marriage falling apart via cellphone, a set of four langorous cows, and a drunken Thanksgiving performance of Angels in America that ends in disaster as snow begins to fall in “lotus flakes.”

The five other stories are all equally rich. Lee’s narrative flow is ironic, amusing, knowing, humane, energized by unexpected words and surprising turns of phrase, and deepened by a sophisticated layering of background news about Soviet-era Poland, Hong Kong during the Vietnamese boat people crisis, Hurricane Katrina, and the Starr report.

The House at Belle Fontaine By Lily Tuck

This new collection from a master, winner of the PEN Faulkner for Siam and the National Book Award for The News from Paraguay spans the globe, with poetic and absorbing stories set in Paris and provincial France, Bangkok, Lima, Long Island, and en route to Antarctica.

Tuck is a precise stylist; she often uses the fragmented narratives to present many points of view or many points in time, giving many of these stories an eerily disturbing quality. In the title story, memories of two plane crashes decades apart lend a portentous air to a quiet dinner between an American woman and her frail French landlord.

In “Lucky,” the image of a car wreck, and a man convulsing on a stretcher, haunts a couple who witnessed them, the doctor who tried to save his life, as well as his ex-wife, who’s called to identify him in the hospital. In “Ice,” an iceberg that is taller and longer than a cruise ship looms over a passenger who hopes she and her husband survive the journey, and that their marriage will be “more or less intact.” The narrator of “The Riding Teacher,” a geneticist, learns by reading his obituary that Chingis, the Russian-born man who taught her to ride as a girl, and changed her best friend’s life, was descended from Genghis Khan.

“Bloomsday in Bangkok,” set during the Vietnam War, opens with a mysterious line: “In June, after Frank, Claire saw monkeys, monkeys instead of people”—and unfolds with increasing horror as Claire senses the unraveling of Frank, an Air Force captain who made long journeys up-country without saying where—“Laos, probably,” she thinks. A woman who was a child in 1940, when her parents moved from Paris to Lima for five years, narrates “Perou.” But this story is not about her, or her parents. It’s about what happens to her nurse, Jeanne, who is cut off from her family in Brittany.

Between My Father and the KingBy Janet Frame

This posthumous collection is a must-read for Janet Frame fans. Her startlingly original work drew upon her impoverished New Zealand childhood, her years in mental asylums in her 20s (she was misdiagnosed as schizophrenic), and her strength as a writer after she was saved from a lobotomy after she was given an award for her first story collection, The Lagoon and Other Stories. She published widely, won the Commonwealth Award in 1989, and became an international celebrity upon the release of Jane Campion’s 1990 film An Angel at My Table, based on Frame’s three-volume autobiography. (Hilary Mantel dubbed it “one of the classics of autobiography.”)

When Frame died in 2004, she left behind two novels—Towards Another Summer, published in 2009, and In the Memorial Room, coming out this fall—and dozens of previously unpublished stories. The New Yorker and Granta published several posthumously. They are included among the 28 stories in this new collection, written between the 1940s and the 1980s, in addition to 15 previously unpublished stories. There are gems here, beginning with the title story—a child’s-eye view of her father’s injuries from the “Great War” when she discovers a promissory note to the king.

Two previously unpublished stories draw from her days in psychiatric hospitals. In “Gorse Is Not People,” a young woman relegated to the asylum since age 10 because she is a dwarf, turns 21, and receives terrible news. Comedy takes on a new meaning in “A Night at the Opera,” as patients in the “disturbed” part of a psychiatric hospital watch a Marx Brothers movie.

“The Spider” was likely inspired by Frame’s experience at New York literary parties. A young couple at a party provoke envy and nostalgia (“memory that, bypassing the preservative process, turns sour”) among three women in an older crowd of composers, painters, and writers. With her short black velvet dress and her blonde hair shimmering “like a multitude of strands of fine sunlit web,” the young woman looks like a beautiful spider. The young man is handsome, with a dark-eyed gaze. As the two kiss in the middle of the party, the three older women watch silently, crowded by their “lost, discarded, outgrown, obliterated, murdered, mourned-for selves.”