Comedian Sam Jay opens her new HBO stand-up special, Salute Me Or Shoot Me, by admitting not only that she’s wearing Spanx, but because she doesn’t know how to pee in them, she’s standing before the audience now with a wet ass. Whether any of that is true or not is irrelevant, because she literally has made herself the butt of the joke.

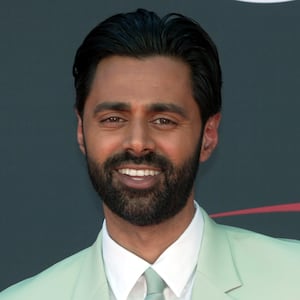

Hasan Minhaj, on the other hand, found himself clowned upon and debated this past week not because he acknowledged in a New Yorker)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-communications/hasan-minhajs-emotional-truths__;!!LsXw!RIGxTfHXH4k4FL2G33VOS4XWar3to-Jp47ROSbcLyhPjXTASkNHYhZXyftgu8A9KLtm50NOMXVpRYvNeqjM-K8sMfsXllqwADQ$">New Yorker profile that he had lied in his comedy specials, but because he lied for the wrong reasons.

What’s the difference?

“Every story in my style is built around a seed of truth,” Minhaj explained to the magazine. “My comedy Arnold Palmer is 70 percent emotional truth—this happened—and then 30 percent hyperbole, exaggeration, fiction.”

That formula is fine enough, and many comedians follow something similar. When you hear a stand-up say something happened to them this week or yesterday or even earlier that day, you know they’ve been freezing that joke in time for months, if not years. Similarly, when a comedian recalls an experience from their past, they might change the dialogue to things they wish they had said in the moment, or change small details because otherwise, they’d be in the non-comedian position of explaining “you had to be there.” The comedian’s expertise is to reframe the experience in the retelling so you felt as if you were there.

Which is exactly what Whoopi Goldberg was saying this week on The View, in defending a comedian’s right to embellish stories: “If you’re gonna hold a comic to the point where you’re gonna check up on stories, you have to understand, a lot of it is not the exact thing that happened because why would we tell exactly what happened? It ain’t that interesting.”

Audiences don’t expect absurdists or surreal one-liner observational comedians like Steven Wright or the late Mitch Hedberg to hew to 100 percent accuracy. Nobody would be expected to believe one of Wright’s first jokes on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show in 1982, when he quipped, “Last summer, I drove cross-country with a friend of mine. We split the driving. We switched every half-mile.”

Other comedians who perform in character (or caricature) already have signaled to us that we shouldn’t take them sincerely, whether it’s the late Rodney Dangerfield claiming he got “no respect” or the current Anthony Jeselnik telling jokes that make him seem like the worst human in the world.

And then there are comedians in the mold of the late Andy Kaufman, who deliberately misled audiences into bafflement, wondering if anything he said or did were legitimate.

All of those lies, though, work in service of the joke. They’re intended to make you laugh more, laugh harder.

It’s completely different when you’re lying onstage for personal and professional gain. Take the blowback Steve Rannazzisi received once the world learned he’d been making hay for more than a decade by pretending he had to escape the World Trade Center during the 9/11 attacks. That’s the kind of lying-on-your-résumé offense that works in your favor until you’re found out, whether you’re a politician, a college athletics coach, or even a comedian.

Somewhere in the middle is the kind of fib Sebastian Maniscalco employed in his most recent Netflix special, 2022’s Is It Me?, in which he claimed a student at his kid’s school started identifying as a lion, leading the teacher to install a litter box. Maniscalco copped on The Last Laugh podcast to making that up, saying: “It’s a story that I actually heard from somebody.” Except it turns out he heard it from Joe Rogan, who later had to admit he had merely echoed a Republican’s debunked claim without the benefit of a “Jamie, can you pull that up” fact-check. Maniscalco bemoaned sensitive audiences for getting “really hopped up in regards to things that comedians are saying and think it’s true.”

That relationship between comedians and their audiences has changed greatly in the podcast era, with hours upon hours of raw audio where comedians are seemingly more sincere and open about their lives and opinions, while their audiences become more loyal and sometimes develop parasocial bonds with the performers, thus making that line blurrier when the comedian is back onstage, telling jokes of varying veracity.

In the same interview with The Daily Beast, Maniscalco went on to say: “I just don’t know when it became like, certain things are off-limits when it comes to humor. That’s what comedians do. They point out everything that’s going on in life and put a humorous spin on it. But nowadays, that doesn’t seem to be the case.”

But when your joke is about something that isn’t actually going on in life, is the spin humorous for the sake of humor, or to score political points and/or curry favor with certain audiences?

Which brings us back to Minhaj, who doubled down last year in his interview with The Daily Beast, by claiming sincerely that the “anthrax” incident involving his young daughter we now know he invented for his most recent special “was just a sobering wake-up call.” Not sobering at the time for his comedy, but for his personal life.

“It was really terrifying,” Minhaj told Last Laugh host Matt Wilstein. “There really is this thing where people talk about, ‘Oh, comedians need to push the envelope.’ But I remember in that moment going, oh shit, sometimes the envelope pushes back. There are consequences for what you say and do. And if it hurts the people that count on you the most, and someone who is so innocent like my daughter, I’ve really got to reevaluate and examine what I’m doing here.”

After the New Yorker piece came out, Minhaj defended himself by saying that all his stand-up stories)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/hasan-minhaj-responds-made-up-jokes-claims-1235591585/__;!!LsXw!RIGxTfHXH4k4FL2G33VOS4XWar3to-Jp47ROSbcLyhPjXTASkNHYhZXyftgu8A9KLtm50NOMXVpRYvNeqjM-K8sMfsU2DoQtaA$">that all his stand-up stories “are based on events that happened to me. Yes, I was rejected from going to prom because of my race. Yes, a letter with powder was sent to my apartment that almost harmed my daughter. Yes, I had an interaction with law enforcement during the war on terror. Yes, I had varicocele repair surgery, so we could get pregnant. Yes, I roasted Jared Kushner to his face. I use the tools of standup comedy—hyperbole, changing names and locations, and compressing timelines to tell entertaining stories.”

But when Minhaj claims his interaction with law enforcement was what made him become a comedian, or that an imagined emergency room trip for his daughter fundamentally shifted his comedic outlook, that hyperbole makes his audience perceive and treat him differently.

And that’s no laughing matter.