Channeling the open-plains lyricism of Terrence Malick’s 1973 masterpiece Badlands and its modern spiritual offspring, Andrew Dominik’s 2007 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (not to mention David Lowery’s even more recent Ain’t Them Bodies Saints), David Mackenzie’s Hell or High Water concerns two brothers on a bank-robbing spree through West Texas, and the just-shy-of-retirement ranger intent on catching them. It’s a well-worn premise made fresh by the fact that these poor crooks aren’t driven by greed, but by a desperate desire to save their family ranch, and a bone-deep anger at the predatory bank looking to foreclose on it. That motivation lends this crime saga an of-the-moment timeliness to it—though it’s the film’s ominous atmospheric stillness and contemplative fatalism that truly makes it such a well-timed antidote to the cacophonous CGI-infested letdowns of this summer movie season.

Written by Sicario scribe Taylor Sheridan (whose script topped 2012’s “Black List,” the collection of Hollywood’s best unproduced screenplays), Hell or High Water requires only minutes of action and dialogue to fully establish its protagonists and their unfortunate circumstances.

Commencing with a circular pan around a parking lot outside a bank—where a graffitied message laments, “Three tours in Iraq but no bailout for folks like us”—Mackenzie’s camera soon settles on two masked, hooded gunmen forcing a teller to empty out the establishment’s petty cash drawers before opening for business. It’s an efficient heist, albeit one that concludes with hotheaded Tanner (Ben Foster) giving the just-arrived bank manager a pistol-butt-to-the-face farewell. Cooler Toby (Chris Pine) isn’t pleased with this bit of excessive violence, but as their car careens through back alleyways while cop sirens begin to howl, he too gives in to the euphoric rush of an illicit job well done.

Two more stick-ups quickly follow, including one performed solo by Tanner as Toby finishes a meal at a diner and—grateful for the waitress’s kind offer of a job—leaves a gigantic tip. Along with a visit back to the homestead, where Tanner remarks upon the abode’s deterioration and the cattle’s emaciation, as well as gazes at the bed where his mother spent her final days while he was in prison, these early scenes are marked by conversational exchanges that reveal backstory and personality details in unassuming drips and drabs. Hell or High Water defines its characters in quick, sharp brushstrokes, just as it suggests its milieu’s financial hardship, and the forces behind its decay, via a series of early images of the duo’s car driving past signs that read “In Debt?” and “Debt Relief.”

As it turns out, there’s a method to Toby and Tanner’s mayhem: namely, to rob various Texas Midlands bank branches, launder the stolen money through a nearby casino, and then use those funds to pay Texas Midlands what’s owed on their ranch’s outstanding mortgage. In essence, they’re robbing Peter to pay Peter, all so Toby can leave the property to his estranged sons. And they’re doing so in small enough individual hauls to avoid attracting the attention of the feds. Nonetheless, their gun-toting romp is fraught with bad omens, not least of which is wild-man Tanner’s fondness for drinking too much (“Who the hell gets drunk off of beer?” he questions while having another brew) and, later, his decision to bring a couple of assault rifle-shaped bags with them on their jobs.

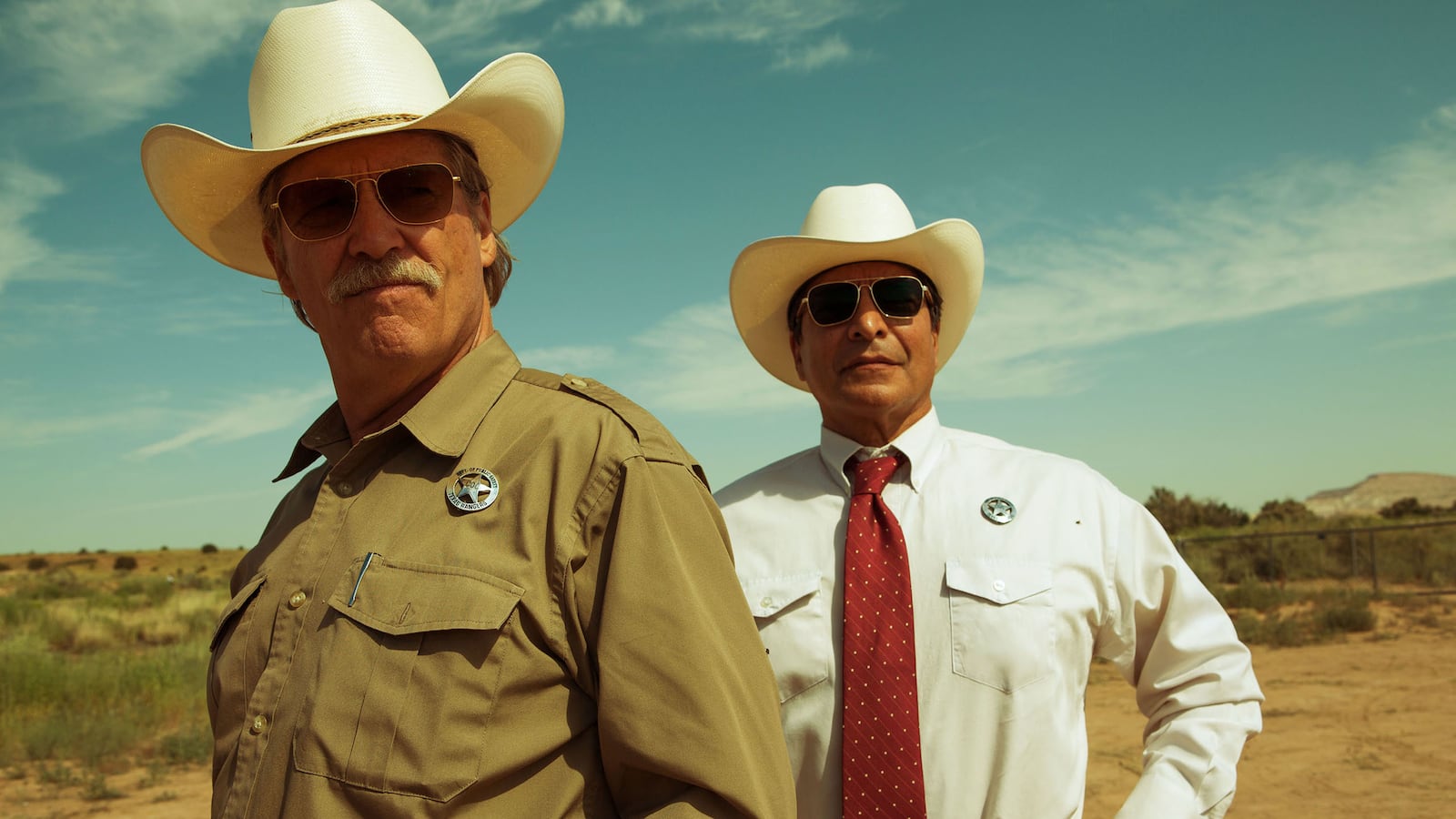

A more immediate problem is law enforcement, which here comes in the form of Texas Ranger Marcus (Jeff Bridges) and his partner Alberto (Gil Birmingham), whom the former incessantly bombards with barbs about his “half-breed” Native American-Mexican heritage. Theirs is a combative rapport, and like Toby and Tanner’s, it’s developed over numerous, natural back-and-forths that are infused with a sense of shared history. As the two embark on their pursuit, Hell or High Water proves content to merely sidle up alongside its primary pairs as they deliberately set about their (inevitably converging) paths. There’s a leisurely pace to the material, which isn’t the same as sluggish; instead, the proceedings’ unhurried momentum amplifies the feeling that inescapable doom looms just over the vast, imposing horizon that Mackenzie (a stylistic chameleon who’s following up 2014’s gritty prison drama Starred Up) often captures in gorgeous magic hour panoramas.

Most hauntingly evoked in the image of Toby and Tanner palling around in silhouette at dusk, Hell or High Water’s characters are all on the verge of becoming ghosts, left to wither away and disappear in a gone-to-seed environment about to do likewise. Mackenzie’s assured direction so ably conveys this notion in visual terms that it’s a shame when Sheridan’s script forces its subjects—most notably Alberto, in a speech equating the stolen-land plight of Native Americans to that of Texas’s bank-exploited whites—to spout on-the-nose exposition about the story’s themes. Courtesy of Pine and Foster’s superbly lived-in performances, Toby and Tanner’s fury at their unjust economic mistreatment is visible in their determined, sorrowful eyes, and doesn’t require the film to belabor its The Grapes of Wrath-ish point through overt statements of purpose.

Such gestures, however, do little to undercut Hell or High Water’s electric power, nor its ultimate, mature recognition—during an unbelievably well-orchestrated finale and coda—that two opposing facts about a situation can be true at the same time. Rather than reconciling his scenario in tidy moralizing fashion, Mackenzie simply lets both perspectives on his story exist in uneasy conflict. Just as shrewd, it allows Jeff Bridges to deliver what may be one of the most colorful, and yet nuanced, performances of his career.

With roughneck charm, the actor speaks in a deep, borderline-slurry southern drawl that makes it sound like his mouth is half-coated in peanut butter—hearing him say “They bopped you in the schnozola, huh?” is one of the movie year’s finest highlights. And he dons and removes his Stetson (and places it, while seated, on the tip of his boot) with preternatural old-world grace. Embodying Marcus as a cowboy futilely clinging both to a past that continues to recede, and a present constantly shifting under his feet, it’s a turn that imbues a potential caricature with profound depths of knotty feelings, and is epitomized by a post-climactic outburst of simultaneous satisfaction, joy, and hopeless grief that also, in the end, sums up the mood struck by this remarkable genre gem.