The reason eyewitness testimony requires corroboration in a criminal trial is that memory—an internal account that can’t be verified by anyone else, and which may consciously or unconsciously change over time thanks to a variety of factors—is inherently unreliable. Yet in 1990, a jury decided that George Franklin was guilty of the 1969 murder of Susan Nason, the best friend of his 8-year-old daughter Eileen, based solely on the adult Eileen’s claim that, while staring into the eyes of her own child, she was suddenly beset by a heretofore-forgotten vision of her father fatally striking Susan with a large stone.

Eileen thus became the poster child for the modern theory of repressed memory, which contends that when faced with unthinkable trauma, people often lock recollections of those experiences away in a deep, dark subconscious compartment, where it can have no effect on their day-to-day lives. These individuals are, in effect, completely unaware of their memories, until they spring forth due to some unexpected stimuli. That was certainly the story forwarded by Eileen, and embraced by prosecutors (and their team of experts) who jumped at the chance to use Eileen’s unique circumstances to put George on trial. What ensued was a court case like few others, hinging as it did on the trustworthiness of star witness Eileen, a freckle-faced redhead who admitted that she had grown up very close to her father, but who was now convinced that she had seen him fiendishly take the life of her childhood friend.

Writers/directors Yotam Guendelman and Ari Pines’ four-part Showtime docuseries Buried (Oct. 11) is a tale about sexual abuse, family dysfunction, and the nature of reasonable doubt. It’s mostly, however, an investigation into the plausibility of Eileen’s brand of repressed memory. Since there was no other physical or anecdotal evidence that suggested George had been directly responsible for Susan’s slaying, the prosecution relied exclusively on Eileen’s unsubstantiated version of events. From the get-go, however, Eileen wasn’t very believable. She said that she and George picked Susan up on the morning of her disappearance, only to switch gears and say it happened in the afternoon. She admitted that she had a book and film deal in the works (which eventually resulted in the 1992 TV movie Fatal Memories starring Shelley Long as Eileen), thereby revealing her financial motive in seeing her dad get convicted. She also came to remember being raped by one of George’s friends, but after saying the attacker was Black, she flip-flopped and asserted that he was actually her white uncle (the confusion, allegedly, stemmed from a Jimi Hendrix poster hanging on the wall).

Most damning of all, she told numerous people that she first remembered George’s homicide while under hypnosis, but then—surely after learning that hypnosis-related evidence is inadmissible in California courts, because it can’t be trusted—she altered her narrative and denied having ever undergone the procedure.

As true-crime aficionados know, eyewitnesses are wrong at least as often as they’re right, purely because of the way the human mind works. Consequently, Eileen comes off terribly in Buried. On the stand, she appears to be performing for an audience—something she’d later do on The Oprah Winfrey Show, Larry King Live, Today and countless other television programs—and Guendelman and Pines’ shrewdly edited compendium of audio interviews, courtroom footage, textual transcripts and documents, and dramatic recreations poke several holes in her integrity. In particular, a staged sequence in which George heads off to commit murder as the sunlight changes from morning to afternoon (in line with Eileen’s shifting version of events) underlines her inherent dubiousness.

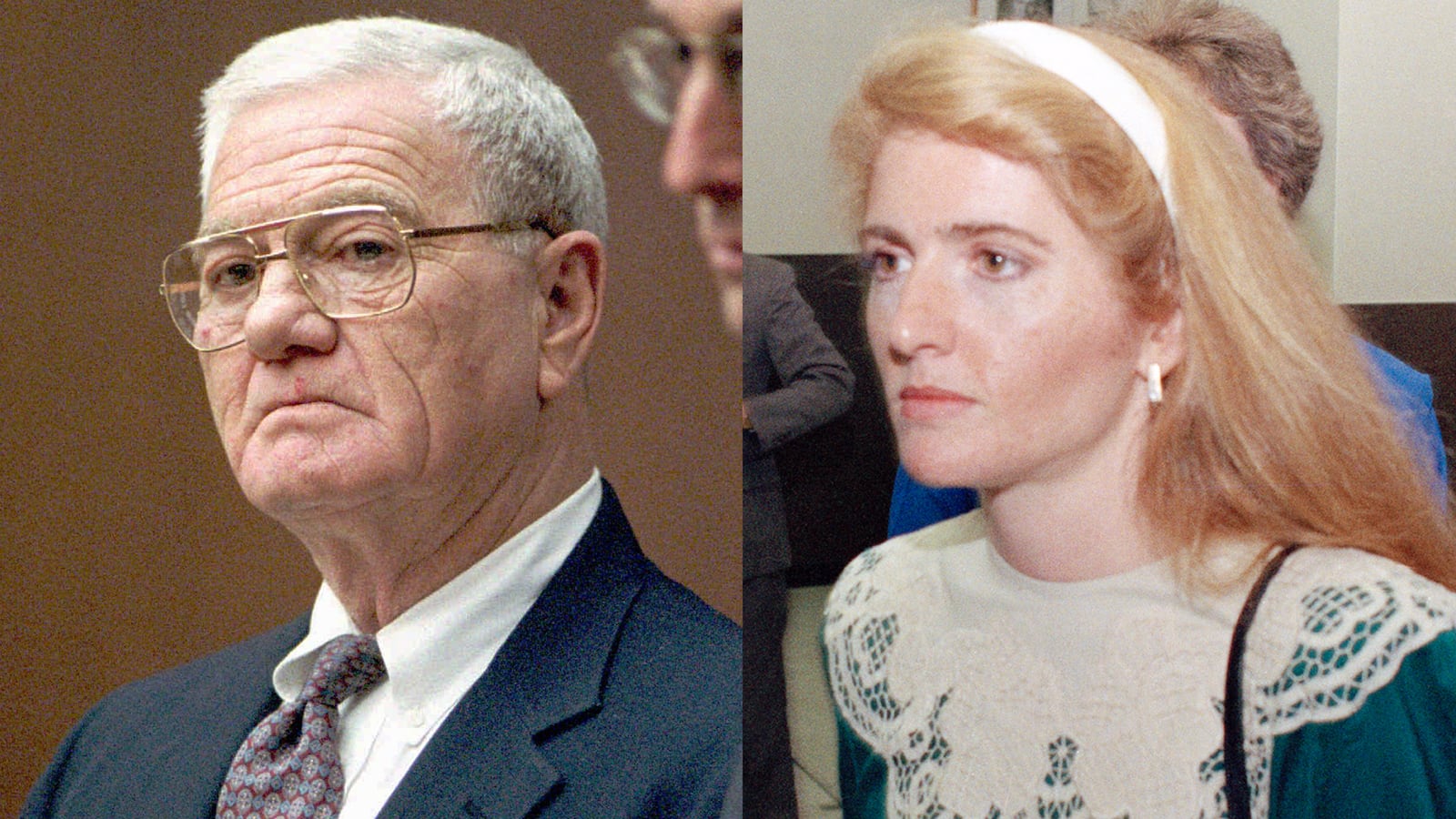

A still from Buried.

Courtesy of SHOWTIMEAdditionally calling Eileen’s account into question, the details she supposedly remembered about George’s attack had all been previously reported on in the press—thus meaning her insight was based on public-domain information—and to prove this point, Guendelman and Pines smartly juxtapose her testimony with corresponding passages from newspaper articles. That this fact was prevented from being introduced in court was a key cause of George’s original life-sentence conviction—well, that and the revelation that he was a pedophile who had physically and sexually abused his five children. Like George’s appeals lawyer Dennis Riordan, Buried recognizes that the accused was a monster who deserved to be behind bars, while nonetheless suggesting that repressed memories are far from airtight, and certainly not enough on their own, to secure a just conviction.

Buried gives ample time to district attorneys who were sure that Eileen was telling the truth, and to defense attorneys—namely, voice-of-reason Douglas Horngrad—who viewed repressed memories as “voodoo psychology.” Critical experts also have their say about the many inconsistencies in both Eileen’s yarn and the science for repressed memories. By the series’ final installment, there’s so much to distrust about Eileen’s story that speakers barely even find time to touch upon the underlying, and ludicrous, notion that George willingly brought his impressionable daughter along to watch him assassinate her best friend. When, following George’s initial guilty verdict, Eileen began recovering more memories and accusing her father of being a serial killer responsible for the rape and murder of Veronica Cascio—which she also apparently attended in person—it’s as if she’s deliberately testing the limits of everyone’s faith.

DNA evidence ultimately exonerated George with regard to Cascio’s killing, and in doing so, it made plain the fallibility of Eileen’s repressed memories. The Franklin siblings’ increasingly fractured relationships during this era only exacerbated the sense that multiple motivations were at play here, from Eileen and sister Janice’s desire to see their father punished for the misdeeds he committed against them, to their passive mother Leah’s interest in presenting herself as the loving maternal figure she wished she had been. Factor in Eileen’s hunger for fame, her lingering wounds from a disturbing childhood, and George’s deviant urges, and what’s left is a saga in which the only thing worth rooting for is the bedrock principle that no one should ever spend their life behind bars simply on the basis of a repressed memory.