Nothing goes stale faster than newspaper copy. Wrap a fish in it and see which holds up better three days later. I’m betting on the fish.

But I make an exception for Herb Caen, the iconic San Francisco columnist whose centenary takes place on April 3. Even during his lifetime, Caen was more a monument than a journalist. If you ask native San Franciscans of a certain age to list the things they associate most with the city, Caen’s name shows up right after the Golden Gate Bridge, the 49ers, cable cars, and sky-high rents.

In other words, Caen was built to last. His columns—even the half-century old ones—still entertain. If you doubt me, check out a few.

When Caen received a special Pulitzer Prize a few months before his death in 1997, the award citation called him the "voice and conscience of his city.” They got that right. Although I wish they had found time to mention his humor, his geniality, and the nonchalance with which he crafted a must-read newspaper column six days a week for more than a half-century.

Yet, at his death, even the San Francisco Chronicle—his home base for most of his career—was forced to admit that Caen was “largely unknown in much of the nation.” Within the range of the newspaper’s daily deliveries, matters were very different. Caen’s following was so strong that editors feared that as many as a fifth of the paper’s subscribers might cancel without his column to keep them informed and entertained.

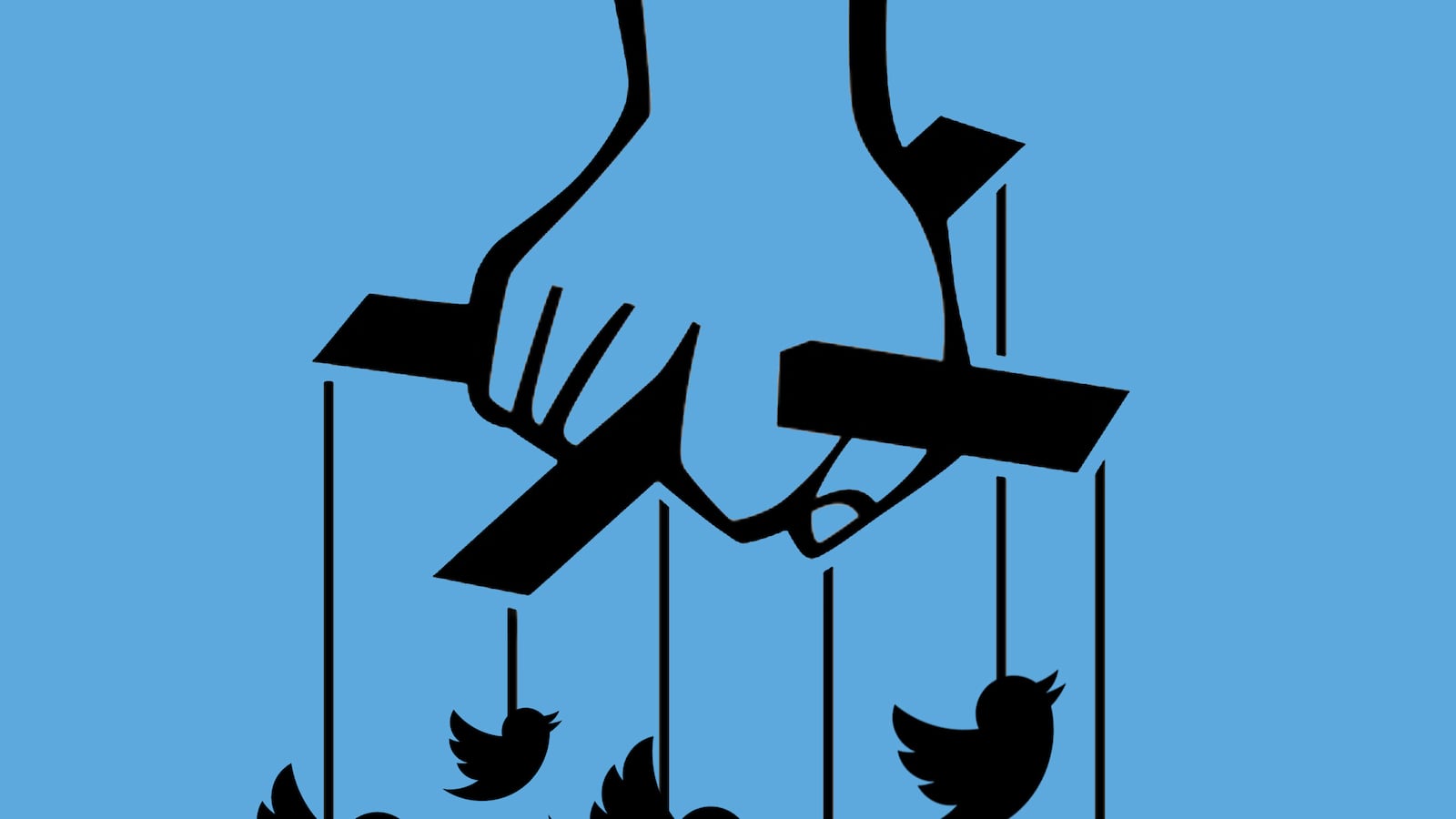

No one lives forever, but I must admit disappointment that Caen didn’t survive long enough to make his mark on the World Wide Web. If Twitter had been around during the Cold War years, Caen would have been much more than a local hero—he would have been a global media one-man brand.

In fact, Mr. Caen ought to be called the grandfather of the tweet. His daily column was just a collection of bits and pieces. He called it “three dot journalism.” But I prefer to think of it as the prototype for today’s social networking.

Over the course of a thousand words, Caen would serve up between 20 and 30 bite-sized observations. Each was concise and ready to go viral—although back then, Caen’s wit would be spread via conversations at the water cooler or neighborhood bar or family dinner table.

If you read Caen, you got the news, but you also received a judicious dose of gossip, jokes, opinions, reviews, announcements of future events, insider scoops from City Hall, true crime stories, puns, sports talk, human interest tales, and social commentary. If it wasn’t in Caen’s column, it wasn’t worth knowing, at least not for those operating within the city limits of San Francisco.

Just imagine what he could have done with the Internet instead of just a typewriter!

A typical column from 1980 tells us that Marlon Brando has been phoning Cupertino in an attempt to get shares in the Apple Computer IPO. Caen then reports that Stevie Wonder, currently staying at San Francisco’s Sheraton Palace, created a mob scene by giving an impromptu performance in the hotel bar. He shares a rumor that Las Vegas casinos have been pumping extra oxygen into the air to keep gamblers awake and at the tables. He touts a charity performance by Joan Baez, gives an account of a caterer foiling a carjacking by defending herself with a gallon of apple juice, and shares juicy details of a vice squad arrest on O’Farrell Street.

But you probably can’t believe everything in this column—for example his secondhand story that Ronald Reagan responded to the shooting of John Lennon by admitting: “I hated his father’s politics, but I love the way his sisters sang.”

Caen wasn’t even a native San Franciscan—he was born in Sacramento in 1916. But he had a response for those who scrutinized the details on birth certificates. (There are still a few of those around, no?) He explained that nine months before his birth, his parents were visiting San Francisco. Take that, you birthers!

His first column in the Chronicle, entitled “It’s News to Me” appeared on July 5, 1938, and for the next sixty years he was a man about town almost every evening. No one was more connected in those days before Internet connectivity. The Chronicle once reported that “in a typical year he dropped 6,768 names, got 45,000 letters and 24,000 phone calls.”

Two years after Herb Caen’s death, Jack Dorsey moved to San Francisco, where he later established the company Twitter. Coincidence or karma? You be the judge. For my part, I find it all-too-fitting that less than one mile separates the Twitter CEO’s desk from Herb Caen’s old office at the SF Chronicle. As I see it, Twitter just took over from where Caen left off.

Even today, people involved in social media could learn from Caen’s example. Here are the rules he wrote by:

Make it informative and funny in 40 words or less: No journalist of his day was more concise than Herb Caen. In just a few words, he could tell you the facts and also keep you amused. Often it took just one sentence, and rarely more than three.

Be accessible and responsive: People who phoned the San Francisco Chronicle with the expectation of reaching Herb Caen’s assistant or receptionist were frequently surprised when he answered the call himself. They thought they would deal with intermediaries, but instead had the undivided attention of the most influential journalist in town. Caen realized that this accessibility kept him informed and provided him a steady stream of tweet-worthy items for his columns.

Give credit to others: When Caen heard a clever witticism or a funny joke, he would share it in the column—but always give the name of the person who fed him the material. They didn’t call it retweeting back then, but this was exactly what Caen was doing. And his willingness to share the limelight ensured that the cleverest people in San Francisco kept sending him their humorous one-liners and wry observations.

Treat people as friends, not sources: I once heard someone gripe that “you could bribe Herb Caen with a box of donuts.” That wasn’t a fair criticism. It would be more accurate to say that Caen saw his sources of information as friends, and he applied the ethical standards of amicability and bonhomie to his dealings with them. You didn’t even need to bring the donuts. He would try to find ways of publicizing your event or tell your story, because that’s what friends do. In other words, he understood the importance of sociability even before they called it social networking.

And here’s what you wouldn’t see in a Herb Caen column: You would never encounter those rants that make Facebook and Twitter sometimes seem like the waiting room at an anger management clinic. You wouldn’t find trolling and flame wars and name-calling and all those other virtual behavior patterns that make you consider giving up the web for a 90-day mental detox.

Social networkers could learn from all those things that Mr. Caen didn’t do, just as much as from what he did. If he were around today, the Internet would be, to some degree, a better place.

Happy 100th birthday, Herb Caen. In my book, you are the patron saint of the tweet, and the best way of paying homage is to try to do it the way you did back in the analog age. I don’t think anyone around today can match you. But I’d certainly like to see them try.