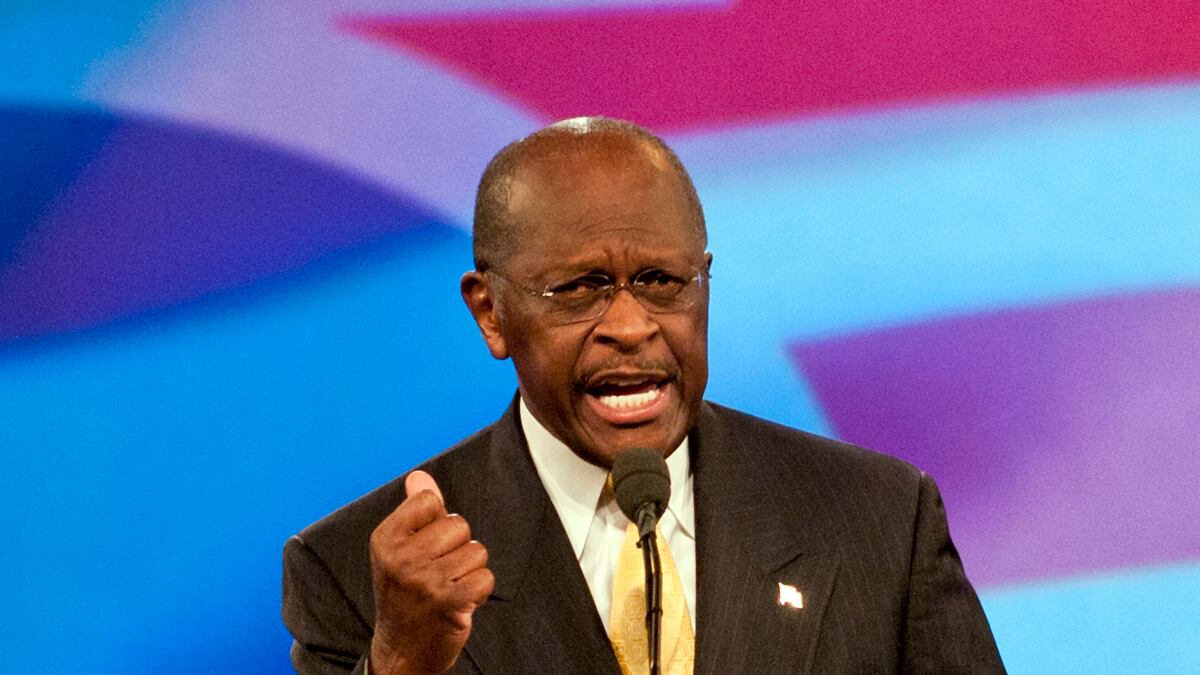

Herman Cain has been firing up crowds with the cadences of a Southern preacher, but he is advocating a gospel that is confounding—even infuriating—many blacks who came of age in the civil-rights era. He is not one of them, and his unexpected surge as a Republican presidential candidate has sparked a vituperative battle between conservative and liberal blacks over his commitment to their community.

Veteran civil-rights activists are questioning Cain’s motives—and mince no words. “I am not aware of anything Herman Cain has done to uplift black people specifically,” said Julian Bond, a former head of the NAACP. “Unless his candidacy, however improbable his chances, gives heart to the least qualified person that there is hope after all.”

Cain lashed back at his critics last week, saying, “Leftist folk in this country that are black—they’re more racist than the white people that they’re claiming to be racist.”

The former pizza executive points to his own success as evidence that racism is no excuse for failure, and has suggested blacks have been “brainwashed” by Democratic ideology. He caused a recent uproar by saying that the poor or unemployed have only themselves to blame.

The way in which Cain and his liberal counterparts have been at each other’s throats, hurling charges and countercharges of racism, is almost unprecedented in the black community. Indeed, there has long been a respectful code that no matter the political differences, they were all members of the same brotherhood sharing similar hardscrabble narratives. GOP strategist Ron Christie contends that the “knives are out” for Cain because “Democrats recognize that he could splinter the community’s monolithic view of the party—they’re afraid of what he represents.”

At the heart of the friction is an age-old disagreement going back to Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington over the ideology of empowerment: advancing through hard work and ambition versus federal assistance and cultural adaptation. In his memoir, Cain says that one of the lessons his father taught his children was “not to feel like victims.” Mary Frances Berry, a former member of the Civil Rights Commission, said that his message of “responsibility and self-determination is very appealing to a lot of blacks.”

As he travels the country, Cain tells largely white conservative crowds what they want to hear: that federal assistance and entitlement programs for the poor and minorities need to be restructured, that people need to seize the initiative and help themselves. Economic problems and social ills, he says, “need to be addressed at the state level,” not by the federal government.

He is, of course, talking about the very federal assistance and protections that helped blacks in the ’60s and ’70s, from the Civil Rights Act and minority set-aside programs to affirmative action. His is a pointed message of urging blacks not to rely on handouts from the government and the white-dominated establishment. But liberal blacks counter that after decades of oppression and discrimination, self-reliance can’t be the only avenue for black advancement.

“There is nothing wrong with a philosophy of self-help; indeed, it can be admirable,” says Bond. “But it cannot possibly be urged on others if it ignores forces like white supremacy and its accompanying evil, poverty, which stymie individual and group advancement.”

By contrast, some prominent black scholars have applauded Cain’s ability to get traction on a point of view that relatively few in the community have embraced.

“The claim of liberal blacks that black America is victimized by the larger white community is nonexistent today,” says Shelby Steele, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. “There is a black man who is president. Blacks lead corporations. There is nothing blacks can’t achieve in this country—and that’s what Cain is saying.

“But the centerpiece of the black civil-rights ideology, still today, is that we are victims, and blacks who do not ascribe to that thinking are accused of not really being black, of being Uncle Toms.” Steele says that “you’re still living off of the pity of white people … that ‘you’re not victims; you can achieve whatever you want to achieve.’ And that philosophy is a threat to the status of black identity itself.”

In his effort to attract black voters—90 percent of whom regularly vote Democratic—Cain has created an odd undercurrent, essentially casting himself as a more authentic African-American voice than President Obama. “He’s never been part of the black experience in America,” Cain said.

Although Cain and Obama represent opposite ends of the ideological spectrum, their strategic approach has similarities. In 2008, Obama did not want to be perceived as the “black candidate” and was careful not to appear overly aligned with black liberals for fear of alienating white voters. Privately, many black leaders criticized him as an elitist who didn’t come up through the ranks of the movement. An open microphone picked up Jesse Jackson saying, “See, Barack’s been talking down to black people ... I want to cut his nuts off.” He later apologized.

Some view Cain’s sudden popularly as vindication for the Republican Party, which has long found it difficult to attract black politicians—and black voters. Only two members of Congress are black Republicans.

“Who could have imagined that the leading Tea Party attraction would be an aging, dark-skinned black man who’s openly unintellectual and loud?” asks John McWhorter, an African-American scholar (and Democrat) who has long questioned aspects of the black orthodoxy. “Racism in the Republican Party is greatly exaggerated. Herman Cain is really throwing a wrench into the machinery.”

Political commentator Jamal Simmons, a Democratic presidential-campaign veteran who attended Cain’s alma mater, Morehouse College, says “there are some very conservative elements” in the black community on social issues such as abortion, immigration, and gay rights that could find Cain appealing. “I think without the ‘you lazy people, get up off your butt’ talk, people might find him much more attractive,” says Simmons.

Cain was born in Tennessee; his mother was a cleaning woman, and his father was a chauffeur and janitor. He was raised in the Atlanta housing projects. He candidly admits in his memoir that his father advised him against getting involved in the civil-rights movement—and Cain, who graduated from high school in 1963, took the advice.

He would have been of prime age to take part in protests but says he was “too young to participate when they first started the freedom rides and the sit-ins. So on a day-to-day basis it didn’t have an impact. I just kept going to school, doing what I was supposed to do, and stayed out of trouble. I didn’t go downtown and try to participate in sit-ins … So, counter to our real feelings, we decided to avoid trouble by moving to the back of the bus when the driver told us to.”

What some in Cain’s home state find galling is his Horatio Alger tale of achieving wealth and success in a vacuum. “There are no truly self-made people,” says Stacey Abrams, the Democratic leader of the Georgia House. “But sometimes success helps create a mythology that you alone moved yourself forward.

“I can’t imagine that he wasn’t given a hand—whether it was through state policy or affirmative action. That was an era that reflected a changing political philosophy, and [black] people were helped.”

Another Democrat, state Sen. Vincent Fort, accuses Cain of “buying into the tradition of demeaning black people. I find it appalling that he suggests that black voters don’t know what’s going on. He believes black people are indifferent—that they vote for Democrats because ‘my mama voted that way.’ It’s a racist view about black people—that they can’t be trusted to vote.”

Cain recently took to the airwaves to fume about criticism from black liberals: “The only tactic that they have to try and intimidate me and shut me up is to call me names. It just simply won’t work.”