Before dawn on March 18, a speeding black Ferrari carrying a young Chinese playboy and two half-clothed young women crashed in spectacular fashion on Beijing’s fourth ring road. At first, mystery surrounded the accident. Police refused to name the driver—later reported to be Ling Gu, 23, the son of an influential ally of Chinese President Hu Jintao. After the news broke this spring, government censors promptly deleted photos of the smoldering wreck from micro-blogging sites and blocked the search terms “Ferrari,” “Prince Ling,” and “car sex”.

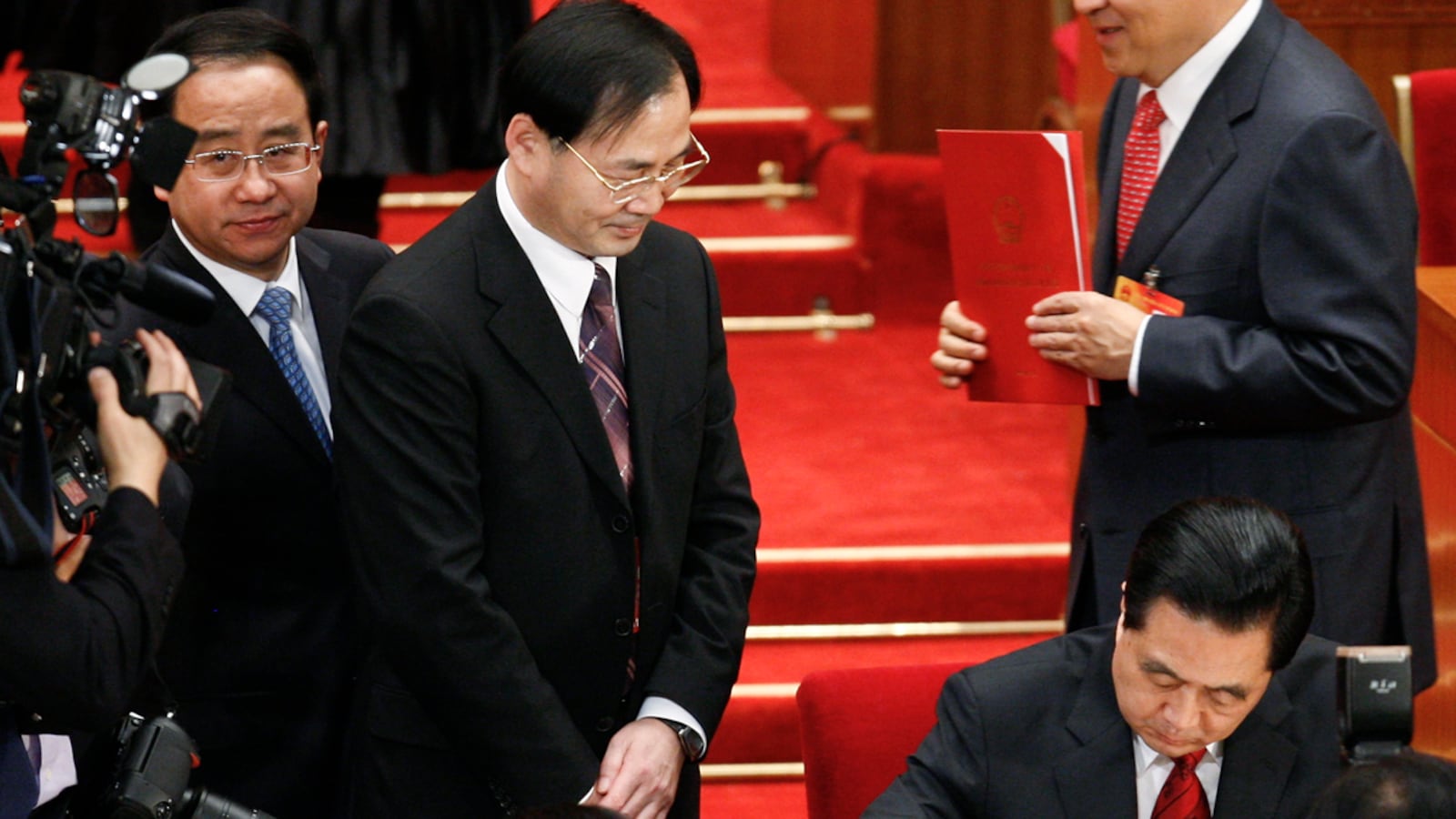

Now, fresh controversy has erupted over the accident, just weeks before a once-in-a-decade political transition. Tellingly, China’s latest political scandal has been dubbed simply “the Ferrari incident.” More than five months after the bloody mishap, the crash became the talk of the town this week after the driver’s father, Ling Jihua, was transferred to a new job that many see as a demotion. On Saturday, state media reported that Ling, 55, had been shifted out of his influential job heading the “General Office” of the communist party’s central committee to a less prestigious though still-important post as head of the party’s United Front Work Department.

Before the transfer, Ling’s position was roughly equivalent that of the White House chief of staff; as such, he was one of President Hu’s key supporters. Previously, reports indicated that Ling had aspired to become part of the powerful 25-member Politburo during the much-awaited 18th party congress expected to open in mid-October – an ambition that now appears thwarted.

News of Ling’s transfer revived the story of the Ferrari incident and further inflamed the growing chorus of Chinese Internet users who resent the pampered lifestyles of the country’s rich and well-connected.

Earlier this week, English-language media confirmed that Ling Gu had been the driver (previously this had only been reported on Chinese websites). On Monday, the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong reported that “Ling Gu had died in the crash” and his death certificate bore a false surname – Jia, meaning “fake” in Chinese. Ling Jihua could not be reached for comment, but sources with knowledge of the situation, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the topic, said Ling Gu, who has not attended class since March 18, is still alive, though may have been seriously injured in the crash.

If the elder Ling’s career has indeed been stalled, he’ll be the second high-profile Chinese official to fall victim to the Ferrari curse this year. China’s top leaders have only just begun to recover from the previous scandal starring an Italian sports car: In February Bo Xilai, the party secretary of Chongqing, was disgraced due to the attempted defection of his top policeman, Wang Lijun, who spent 30 hours inside an American consulate, telling U.S. diplomats that Bo’s wife, Gu Kailai, was linked to the murder of Neil Heywood, a British businessman. (Today state media reported that Wang has been indicted on charges of defection, abuse of power and bribe-taking). Bo’s wife confessed to the murder, but insisted that Heywood had kidnapped and threatened harm to her son Bo Guagua, whose ostentatious lifestyle in the U.K. was notorious. Before his father’s downfall, the Wall Street Journal reported that Guagua once drove a red Ferrari to pick up the daughter of former American ambassador Jon Huntsman’s for a social engagement. (Bo Sr. and Jr. both denied the report).

The result of the two Ferrari incidents has been a media firestorm, which has turned the sleek, Italian sports car into an especially powerful symbol. Ferraris are coveted luxury items in any country. But in car crazy China, where automobile ownership was virtually unknown until the early 1980s, they’re especially glamorous. As a growing number of Chinese make their way into the middle class, a car is often their first big-ticket purchase. Yet as the gap between rich and poor in China has expanded, resentment has grown over the power and wealth of Chinese princelings, children of revolutionary veterans and other connected government officials. And Ferraris such as Ling Gu’s black 458 Spider, which reportedly cost $1 million, have come to symbolize a degree of freedom, mobility, wealth and status that hundreds of millions of Chinese can never attain.

Promotional stunts have also, inadvertently, stirred up grassroots anger over fast-driving Ferrari owners. In the run-up to a local publicity event celebrating Ferrari’s 20th anniversary in the country, a red Ferrari – red’s a lucky color in China – was photographed in May spinning its wheels over an ancient 600-year-old wall in the city of Nanjing. The screeching vehicle left tire tracks on the architectural relic, which dates back to the Ming Dynasty. Outrage erupted online as some saw the incidents as an insult to Chinese culture and tradition.

Chinese bloggers aimed most of their vitriol against Nanjing city authorities who reportedly received $12,000 in exchange for permitting the Ferrari dealership to use the ancient wall. Ferrari apologized to the local government and community for any “damage or offense” caused by the incident. "Unfortunately, an employee of the dealership - not a Ferrari employee - took it upon himself to drive the car in the way that you will see in the video, with the very regrettable result that tire marks were left on the ancient monument,” the company said in a statement in May.

Ferrari has not officially commented on the Ling scandal. Despite the vitriol, the company’s sales in China haven’t suffered; in fact, over the past year, they’ve grown by 62 percent.