Jill Bialosky is an energetic, focused fixture on the New York publishing scene—a poet, novelist, and long-time editor at W.W. Norton, with authors like Nicole Krauss, Lan Samantha Chang, Eavan Boland, Robert Pinsky, Honor Moore, and Mary Roach.

Bialosky can be seen often at literary gatherings in the Hamptons and New York City, awhirl in the crowd, heading from one friend or colleague to the next, or reading from her own work, with a distinct Midwestern twang, or at summer writers’ conferences, like the one held in Taos this past July, listening intently as she goes over manuscripts with promising writers.

Privately, for 20 years Bialosky has been haunted by a family tragedy, the death of her adored sister Kim, the youngest of four sisters raised by a single mom in Cleveland.

Kim took her life after an evening out and a spat with a long-time boyfriend who was breaking things off. While her mother was upstairs in their Cleveland home, she wrote a note, slipped into the garage, turned on the engine of her mother’s Saab, and fell asleep. The cause of death: suicide by asphyxiation. She was 21. Bialosky was 10 years older, married, and working in New York.

“My memoir is a ‘psychological autopsy’ of the multifaceted events that conspired against my sister’s will to live,” Bialosky says.

In the years afterward, struggling with feelings of guilt, confusion, and grief, Bialosky wrote about her sister’s suicide “sideways.” Poems in several collections deal with her baby sister, including the poignant “Runaway,” which ends with the line “the sky closed its eyes on our house as if in shame and claimed her.” One of the characters in her most recent novel, The Life Room, takes his life. “He’s an ethereal, soulful, fragile character,” Bialosky says. “He grows lonely and disconnected and isolated and can’t see outside this. Some of my sister is in him. It seemed to me that the only way I could understand what happened to Kim and how she came to the decision in that last hour to take her life was to try to re-create or capture her inner world.”

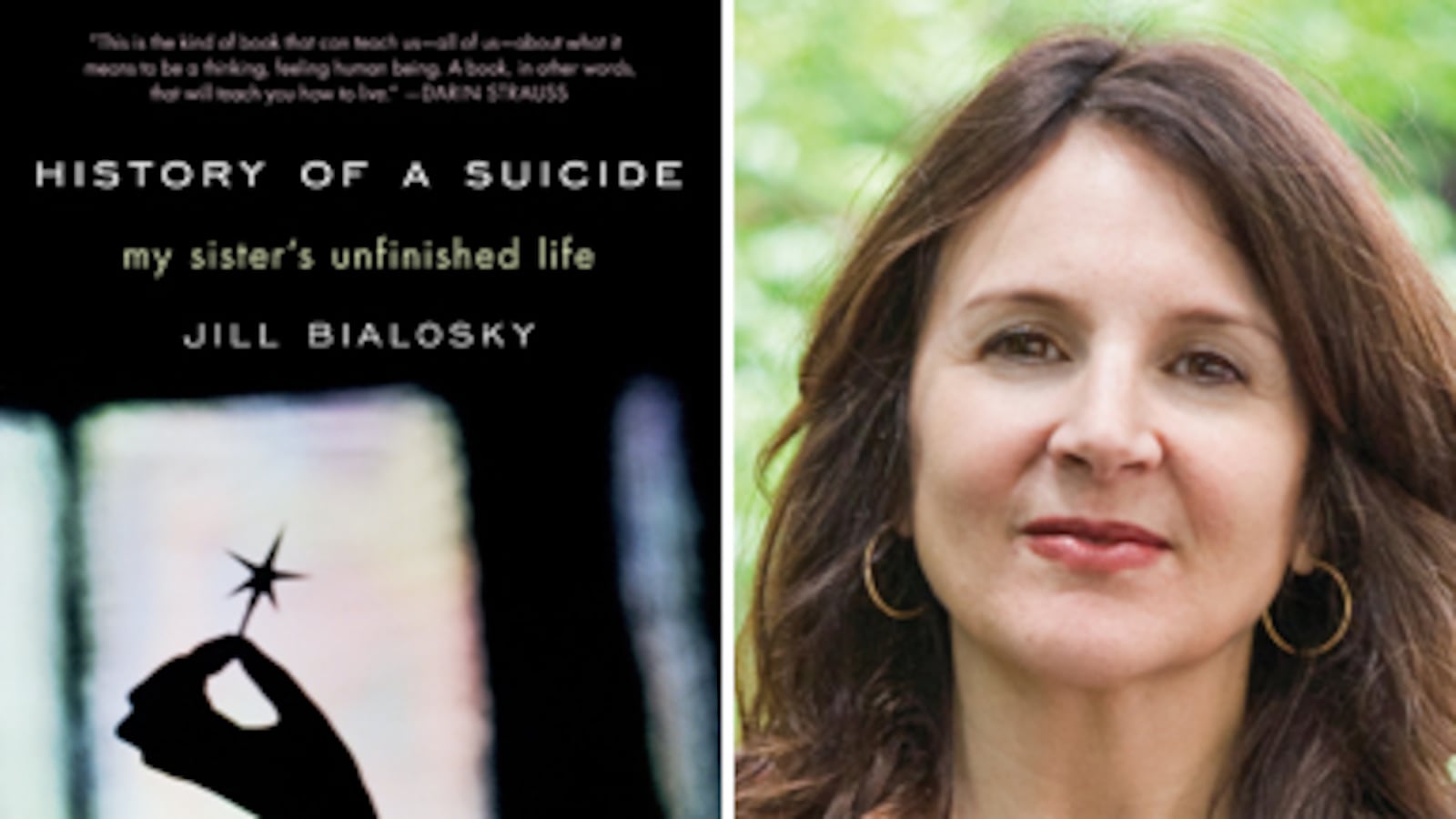

The inspiration and title for her brave and beautifully crafted new memoir, History of a Suicide, came to Bialosky several years after Kim died. For many years it seemed “too painful and personal” to write, she says. Then, as her own son reached adolescence, she found herself struggling to answer his questions about Kim.

Finally, she says, “I felt I needed to take off the veils of poetry and fiction and write about the experience of what happened. I felt it was important to open the conversation about suicide. When a suicide occurs, family members and loved ones are often blind-sided. The shame and guilt are so overwhelming that the suicide is doubly punished, first for her act and then by being silenced. On a very personal note, I felt it was my responsibility as an older sister to give dignity to my younger sister’s life.”

History of a Suicide tells the story of Kim’s life and death, and how it changed those who knew and loved her.

“My memoir is a ‘psychological autopsy’ of the multifaceted events that conspired against my sister’s will to live,” Bialosky says. The term comes from Dr. Edwin Shneidman, a pioneer in the study of suicide; Bialosky consulted him for the book. “In its simplest meaning it is a psychological reconstruction of the intentions of the deceased based on information collected from personal documents, police reports, medical and coroner’s records, and interviews with families, friends, and others who had contact with the person before his or her death.”

Being a mother, more than anything, made it “imperative” to tell her story, Bialosky says. “Suicide is one of the most frightening fears a parent can have.”

Suicide is the fifth leading cause of death among those 5 to 14 years old and the third leading cause of death among those 15 to 24, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Studies show that in 90 percent of suicides, parents had no idea their child was suicidal. In the course of writing the book, Bialosky says, she came to believe that with knowledge and early intervention, suicides could be prevented.

Events like the breakup with a boyfriend, failing an important subject in school, or being bullied, can tap into deep hurts from the past. “With my sister I felt this to be true,” she says. Other factors she uncovered in her research: impulsive behavior, abandonment by a parent (Kim’s father was not part of her life after he left when she was 3), and perfectionism.

“Kim was incredibly hard on herself and could not get past her own frustration about not being further along in her life than she was at the time of her death. Teenagers and young adults who are struggling do not necessarily have more problems than others; they just don’t yet have the skills or ability to reach out and get the help they need. Drugs and alcohol can certainly be a factor and their use can lead to impulsivity.”

Writing History of a Suicide helped Bialosky come to terms with some of her questions. But not all. From reading her sister’s journals and papers after she died, she discovered that Kim had thought about suicide many times.

“But why on that April night did she not find a reason not to?” she writes. “The grieving process is unpredictable. Weeks, months, and years pass, but time passing is irrelevant. It could have been yesterday.”

Years after Kim’s death, Bialosky found solace in a monthly bereavement meeting for survivors of suicides. “We were all struggling in different ways to understand and to relieve ourselves in some way of the anguish and guilt, and we found that people who had not gone through the experience were not always able to understand the confluence of emotions a suicide stirs up,” she says. “There were people in the group who had lost parents to suicide when they were children and others who had just lost a loved one within a few weeks’ time. I realized that my unwieldy journey was no different from that of others who had lost loved ones to suicide, and I was comforted by that.”

Jane Ciabattari’s work has appeared in Bookforum,The Guardian online, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Columbia Journalism Review, among others. She is president of the National Book Critics Circle and author of the short-story collection Stealing the Fire. Recent short stories are online at KGB Bar Lit, Verbsap, Literary Mama and Lost Magazine.