For the fiction lover, the emo cousin, the history buff, and just about every other hard-to-please friend or relative on your holiday gift list, The Daily Beast can recommend books to make your shopping a little easier.

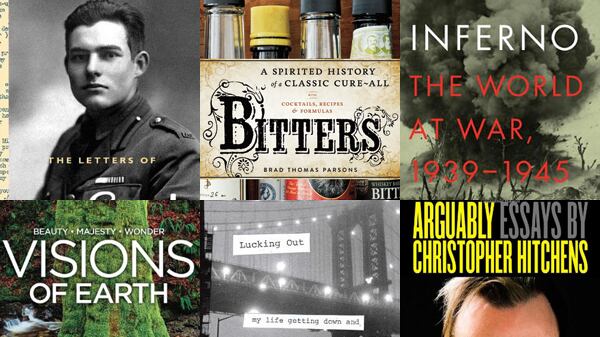

At this point there have been so many books on World War II that most readers might shake their head at ever reading—or giving—another. But stay with us, since these three books by star British historians each offer something fresh: The Storm of War by Andrew Roberts (a Daily Beast contributor) is the best single-volume history of the war, vividly written and deeply researched; Inferno, Max Hastings’s intimate history, covers the war with fresh detail from the grunt on up and with an eye for every corner of the globe; and in The End, Ian Kershaw, Hitler’s biographer, grippingly details the war’s denouement with Germany in ruins, yet Hitler and his henchmen hanging on till the bloody end.

In new collections this year, three of the best essayists alive continued the grand tradition of Montaigne, Johnson, Wolfe, and other legends with work that excited, delighted, and sometimes exasperated us. Read Christopher Hitchens’s Arguably for razor-sharp prose, an encyclopedic mind (which always seems to have just the right quote), and a sense of morality missing from writing today. Read Geoff Dyer’s Otherwise Known as the Human Condition for his brilliantly idiosyncratic take on subjects ranging from W. G. Sebald to Miles Davis to Richard Avedon. Read John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Pulphead for an energetic road trip across weird and wild America, with stops at a Christian rock festival and the pre-life history of Michael Jackson.

Remember when New York was the center of the universe? Remember when every cool musician, artist, and hipster actually lived in Manhattan? Remember when the city was dirty, gritty, dangerous, and therefore interesting? No? Neither do we, but fortunately James Wolcott does in his delicious memoir-cum-eulogy for 1970s New York. Meet Patti Smith, Pauline Kael, and the rats in Lucking Out. And for a full trip of nostalgia, check out Will Hermes’s Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, a full-on tour of all the music that mattered when giants in the making roamed the streets.

We said it last year, but we’re happy to say it again: Best European Fiction 2012 is a gloriously varied and surprising introduction to the vast range of new European fiction. Edited once again by Aleksandar Hemon with a preface from Nicole Krauss, this should be your first stop for any European tour, armchair or otherwise.

So you’ve got this cousin who spends his time listening to confessional music, wearing skinny jeans, and feeling just a bit sorry for himself—so what do you get him? Well, you could try the hallucinatory, sensuous poems of Arthur Rimbaud in a breathtaking new translation by John Ashbery, or you could try Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station for an interior, comic novel of one young poet’s quest to figure himself out (as one critic put it, “avant slackerism”), or you could try the exemplar of confession’s most intimate confessions in The Journals of Spalding Gray.

Aspiring mixologists and well-to-do drunks, behold your fix: The PDT Cocktail Book offers tips from New York’s most meticulous bartender, Jim Meehan, whose popular domain inspired the book’s title and contents. His manual-cum-manifesto contains some 300 recipes, including PDT classics and other concoctions that will make you swoon. Pair it with Brad Thomas Parsons’s Bitters, a homage to the storied elixir and essential ingredient in every Manhattan. Considered a cure-all in the 19th century, bitters are all over the contemporary bar scene, where Parsons samples every brand and flavor, serving up mouth-watering commentary for amateur and seasoned cocktail enthusiasts alike.

On page 283 of Saul Bass: A Life in Film & Design by Jennifer Bass and Pat Kirkham, there is a photo of Bass on a stool in front of a wall of his film posters and corporate logos. That single picture tells almost the whole story, showing as it does the range of one man’s profligate talent. Your eye gets lost in all the familiar sights of your life—in the way the things of your life have looked. People yak about how such musicians as the Beatles wrote the soundtracks for their lives. Well, whatever the visual equivalent of a soundtrack is, that’s what Bass did. From the labels and logos on the Lawry spices and Quaker Oats boxes on your kitchen shelf to the movie credits and posters for such films as Psycho, Anatomy of a Murder, and Good Fellas, this designer, artist, and filmmaker put his stamp on things big and small for most of the last half of the 20th century. Along the way, he pretty much set a standard for excellence in corporate and cinematic design that creative people still measure themselves against. Good luck on that, because no one will ever make looking at the world around you more fun than Saul Bass. This compilation of his work does him proud.

Published in conjunction with the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibit this spring—a phenomenal retrospective of Alexander McQueen’s two decades in fashion—Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty encapsulates the late designer’s legend and stunning couture that, alas, is no longer on display. If your style-savvy sister missed the show, she’ll get a taste of its magic in this book, which features his most radical designs and iconic runway looks. In one way or another, every ensemble reflects his “Romantic” obsession, from Elizabethan gowns to surrealist-inspired looks. He also drew inspiration from the Gothic period, the Flemish masters, and ancient philosophers (for his last complete collection, “Plato’s Atlantis,” models resembled sea creatures in scaly, rainbow-colored dresses).

The first word that comes to mind when thinking of the work of photographer Robert Adams is “quiet.” There are other, more poetic and highfalutin words, such as “sublime,” that might do equally well, but quiet seems to fit the subject better. This 74-year-old artist has spent his life photographing mostly the American West and Northwest, and most of that time he’s spent outdoors. The results have been collected by Yale University Press in a variety of formats designed for every budget, from three affordable paperbacks (This Day, Sea Stories, and a revised and expanded reprint of a singular masterpiece, Prairie) to a glorious boxed retrospective in three hardback volumes, The Place We Live: A Retrospective Selection of Photographs, 1964-2009. Supremely uninterested in the merely pretty, and avoiding the grandiosity of Ansel Adams and the epic reach of Carleton Watkins, Adams has aimed unerringly for a smaller, more intimate scale: the light on leaves in a forest, a bowl of fruit on a kitchen table, the scumble of marine life washed up on a beach. It doesn’t sound like much, set down in words, but gaze upon an Adams photograph and the world around you falls away, your whole being settles down, until all you can see, all you want to see, is the crystalline image before you, shot and printed with an exquisite understanding of tonal values and compositional balance.

Pauline Kael, staff writer for The New Yorker, was the dean of movie critics. Now a new book, The Age of Movies: Selected Writings by Pauline Kael, showcases her work. What’s to relish is discovering stuff like this, as she practically burst into tears on the page writing about Vittorio De Sica: "For if people cannot feel Shoeshine, what can they feel?" And on Jean Renoir: "It's like saying that Oedipus Rex is a detective story." Her pitch-perfect—albeit often bullying—prose mimics the flush of raw responses you get watching great films for the first time.

Samuel Beckett and Ernest Hemingway were “deliberate paupers of style,” as the literary critic James Wood perfectly described them. They freeze-dry their essence into sublime reductions of language. They seem to have used every word only once. But for men who purported to love silences, they sure wrote a ton of words. Cambridge University Press is putting out four volumes of Beckett’s letters, the second manifestation of which has arrived. And it's also publishing every known letter to have been written by Hemingway, a feat that will take 20 years, one for each edition; the first is out now. Jewels like these await: “What if we simply stopped altogether having erections? As in life. Enough sperm floating about the place.” “Visited by partridges now daily, about midday. Queer birds. They hop, listen, hop, listen, never seem to eat. Wretched letter, forgive me. Hope you can read it all the same.” These guys were also painfully funny.

Heston Blumenthal may not look like a mad scientist, but he sure cooks like one—and writes like one, too. As head chef of the three-Michelin-star Fat Duck in Berkshire, England, Blumenthal has made alchemical cuisine a gastronomical movement. He breaks down his time-saving, energy-efficient cooking methods in his mouth-watering book Heston Blumenthal at Home, including 150 recipes for imaginative dishes like salmon with licorice. You don’t have to be a master chef to appreciate what Blumenthal serves up here. He imparts easy tips for the klutz in the kitchen, too, who might just devour every page.

We’re not the only ones who think this book will be under many a Christmas tree this year. British Museum director Neil MacGregor has adapted his popular A History of the World BBC radio series into an erudite yet witty written account of human history told through the stories of the things we’ve made in A History of the World in 100 Objects. Each fascinating artifact encompasses a period in time: sculptures from ancient Egypt and the last Ice Age; an early Victorian tea set; a solar-powered lamp and charger made in 2010. Believe us when we say you’ve never read an art-history book (or any book, for that matter) quite like this one.

A magnificent new collection compiles photographs from National Geographic’s monthly “Visions of Earth” feature, many of them never before published. Images of nature in all its opulence are grouped into chapters by expansive themes like “Radiance” and “Spectrum.” Picture colorful houses on the coast of Greenland; an elephant bathing in India’s Andaman Sea; monks scampering to dinner in Bhutan. The most striking shots juxtapose humanity and nature, like one of Spanish children in a field of yellow flowers, holding fanciful papier-mâché masks over their faces in celebration of a Catalonian festival. There’s also Annie Leibovitz’s Pilgrimage, a photo journal of historical places she visited, from Thoreau’s cabin in Concord, Mass., to Virginia Woolf’s home in the English countryside. She also documents trips to Niagara Falls and Yellowstone Park. The portrait master describes her foray as “an exercise in renewal.”

After “Keep On Truckin’,” R. Crumb is probably best known as the comics artist who composed the now-legendary cover art for Cheap Thrills, the Big Brother & the Holding Co. album featuring Janis Joplin. Fans of country blues and old jazz know better. A musician himself (R. Crumb and the Cheap Suit Serenaders), the multitalented Crumb has been copiously illustrating album covers, playing-card-size portraits, and the occasional concert poster for years. A rabid collector of old 78s since his teens, Crumb loves acoustic folk music of just about every variety, including ragtime, early blues and jazz, even musette (think French accordion). He’s now collected the album art he’s been producing when not drawing comics, thrown in a few movie posters (Louie Bluie), and even a comic-book-like biography of the bluesman Charley Patton (with the text all in French—now, that’s surreal). The result, slipcased in cardboard like an old 78 record, is The Complete Record Cover Collection, the only collection of cover art ever produced that’s as good as or better than the music inside.

In the mid-20th century, around the same time that Eudora Welty launched a prolific literary career, she was honing her horticultural skills in her modest Mississippi garden. The importance of place was a recurring theme in Welty’s work. Even in her earliest short stories, her images of gardens and flora evoke a distinctive Southern ambiance. One Writer’s Garden is a richly illustrated tour of the backyard garden Welty helped restore before she died in 2001. Set against the historical events of the early 20th century, the book also sheds light on the social mores that characterized the South during that period. It also paints a vivid portrait of Welty through the years, a writer who tended to her daylilies and roses with the same passion and precision as she did to her prose.

Every once in a while, a new history book comes along and blows every other one exploring the same topic out of the water. Life Upon These Shores is that book, one that will enliven a run-of-the-mill American-history syllabus. Through dozens of profiles and short essays accompanied by fascinating images of ancient maps, cartoons, momentous documents, and influential photographs, Henry Louis Gates traces the “black experience” in North America, from the arrival of black conquistadors in the 16th century to the election of Barack Obama. There are surprising facts: New York’s African-Americans were banned from attending Lincoln’s funeral march; a black man named Matthew Henson may have trekked to the North Pole before Adm. Robert Peary made the “first” voyage. Gates covers every milestone event (abolition, Reconstruction, the Great Migration, the civil-rights movement) with fresh insight. Scholars will marvel at this imaginative new tome and tribute to African-American history.

Craig Robinson is one of those strangely gifted people who can take numbers and data, put them in graphic form, and make them interesting. Some of what he does in Flip Flop Fly Ball: An Infographic Baseball Adventure is whimsical (a chart shows how high a stack of pennies representing A-Rod’s salary would rise into space). Some is simply jaw-dropping (it’s one thing to know that Ted Williams hit .405 in 1941—it’s something else to see it charted as a graph, from May to September, a season in which he never came close to hitting below .300 and for that matter rarely hit below .400—sometime in late June he locked in around the .400 mark and stayed there for the rest of the season). If everyone were this creative with stats, that side of baseball would be a lot more fun.