When Uncle Sam started peeking at the genitals of U.S. travelers, apologists insisted that his prying eyes were justified. Hadn't terrorists hijacked airplanes on 9/11? John Pistole, head of the Transportation Security Administration, insisted that upset Americans could always choose not to fly.

What he neglected to mention is that his bosses at the Department of Homeland Security intend to use various kinds of body-scanning technology elsewhere in American life. That's clearer than ever if you read the recently updated "privacy impact assessment" that the agency published. It notes that as far back as 2008, DHS personnel descended on the Toyota Center in Kennewick, Washington, where they tested equipment meant to detect security threats in large crowds of people. Folks showing up for sporting events were directed to a special entrance if they were uncomfortable being guinea pigs.

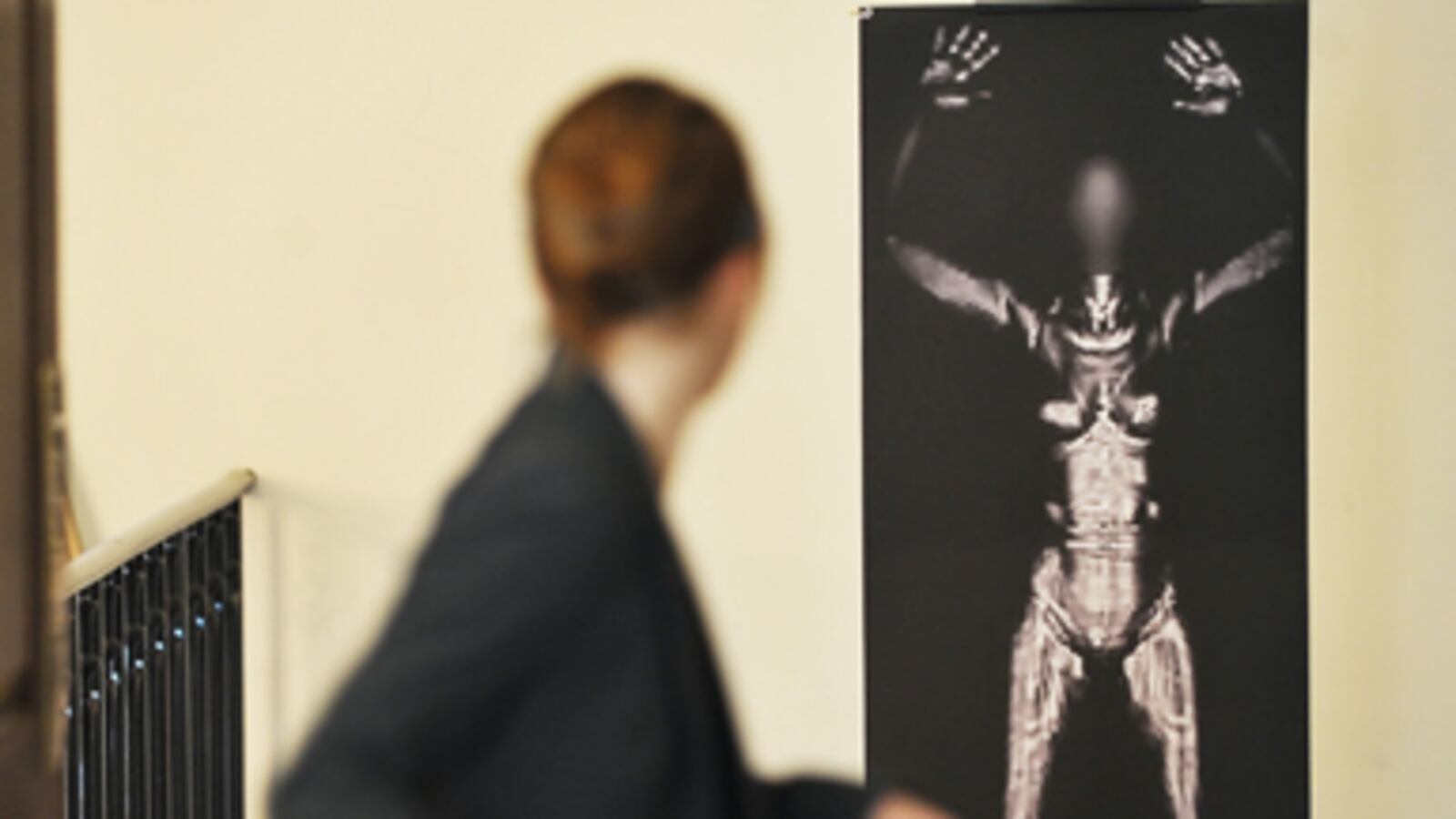

DHS intends to continue publicly testing equipment for the next several years, including sophisticated video surveillance cameras, infrared imaging, ultrasound sensors, and (most controversially) active millimeter wave scans—technology that produces "strikingly graphic images" of the human body, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. As the Cato Institute's Jim Harper notes, the idea is to figure out how government can use the sort of invasive scanning techniques seen in some airports "anywhere DHS wants."

Why?

The official explanation is rather dry. "Patrons approaching large public events" are "attractive targets for terrorists," the agency report notes. And the new technology will "improve decision-making by using a highly automated system that integrates detection systems and prioritizes threats."

Here's the English version: In the future, as people walk from the parking lot of a stadium toward its entrance, they'll be scanned. Sometimes the relevant technology will be sniffing out explosives, detecting metal, or rendering infrared images.

Other times—if all the technology being tested is ultimately implemented—active millimeter waves will peek beneath the clothing of some people in the crowd, rendering graphic images for review by on-site security. And the government bureaucrat of the future will doubtless explain that anyone upset by the virtual searches can opt out by choosing not to attend large concerts or football games.

As yet, no one at DHS is willing to acknowledge that naked scanner technology may one day come to a public place near you. Nevertheless, if you are inclined to put up with them at airports, but troubled by the idea that naked scanners may become common features of American life, it is important to fight back now.

Use of these machines in airports normalizes them. It also generates a lot of profits for the naked scanner industry. Are its stakeholders going to be content with the current market? Already we've empowered a lobby with an incentive for encouraging more scanners. It's in their interest to sell one to every municipality with an outsize DHS grant and a minor league baseball stadium.

And once DHS decided that the technology used in some airports ought to be tested at a sports arena, it revealed something important about its logic: The department is interested in scrutinizing crowds wherever they may be. Air travelers today. Sports fans tomorrow. New Year's Eve revelers in Times Square the year after that. Future anti-war rallies, eventually.

DHS is interested in scrutinizing crowds wherever they may be. Air travelers today. Sports fans tomorrow.

If the technology gets cheap enough, maybe we'll even check crowds at movie theaters, museums, and shopping malls.

Alternatively, we could conclude that it's impossible to protect every crowd of people in America from terrorists with explosives—that even if we completely secured every airport in the country, an impossibility itself, a determined enemy would just move on to train stations, or buses, or kindergarten classrooms.

So long as DHS is charged with protecting every assembly in America from the possibility of attack, its leaders will prove incapable of giving privacy, civil liberties, and cost effectiveness their due. Congress should right the situation. Its members are apparently OK with naked body scans inside airports. So the best reform that has a chance of passing would be to pre-emptively outlaw the technology everywhere else.

Conor Friedersdorf blogs at True/Slant and The American Scene. Follow him on Twitter at Conor64.